This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

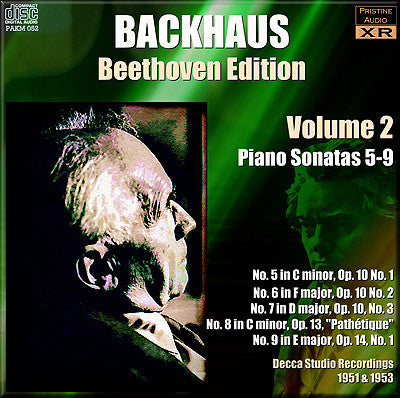

- Cover Art

Second volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

Gramophone's reviewer in 1951 notes some blasting on louder passages on his LP copy, and likewise I had to deal with shortcomings of the recording which I firmly ascribe to the early tape system in use - which was much improved by November 1953 for the later three recordings in this volume. Whether or not the reviewer was hearing disc blasting, there was often a tendency towards a mushy kind of tape hiss to surround the upper frequencies of louder notes and chords, and I've spent a lot of time removing or taming these.

Elsewhere, pitch has once again been susprisingly variable, both in terms of overall tuning, and in clear issues with both tape machines and editing, all of which can now be remedied. Sound quality was generally good - my aim here, which I feel has been achieved, has been to clarify the piano tone whilst reducing background noise and hiss.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 5 in C minor, Op. 10 No. 1

Recorded March 1951

Issued as Decca LXT 2603

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 6 in F major, Op. 10 No. 2

Recorded March 1951

Issued as Decca LXT 2603

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 7 in D major, Op. 10, No. 3

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2809

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13, "Pathétique"

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2903

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 9 in E major, Op. 14, No. 1

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2903

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

Fanfare Review

His feeling for classical balance and his sometimes-impish sense of humor enliven these pieces and give full measure to the music

Volumes 2 & 3

My earlier enthusiasm for the first four Beethoven sonatas by Wilhelm Backhaus cooled considerably with these releases, especially when I came to the “Pathétique” Sonata. Here Backhaus is being either deliberately perverse or uncaringly inaccurate. The introduction is played both much too fast and without the correct dynamic contrasts in the fp chords, and when he moves into the allegro section of the movement, his playing is entirely glib, on the surface of the music, and with strange, uncalled-for ritards when he plays the minor-key melody in the middle. In short, there is nothing to recommend this performance beyond the range of a curio, and there are certainly enough cold and perverse readings of Beethoven out there the way it is.

His performance of the second movement of this sonata is also rather fast and glib—except for the ending, which he suddenly slows down to a crawl. The last movement is OK in both tempo and phrasing, but has all the excitement of stewed prunes.

Backhaus is considerably better in the smaller-scaled sonatas, Nos. 5–7 and 9–11. Here, his feeling for classical balance and his sometimes-impish sense of humor enliven these pieces and give full measure to the music. (In a few places, for instance the final scherzo of No. 10, his method of rubato—shortening certain bars in tempo while slightly extending others to balance out—reminds me of Annie Fischer’s and Craig Sheppard’s approaches.) Backhaus is also good in the quirky opening of Sonata 11; the second movement, again, sounds as if played on autopilot, but he’s good in the last two movements.

In the “Funeral March” Sonata (No. 12), Backhaus plays the first movement with fine classical balance but rather dispassionately. The second movement has lilt and lift, but in the third (the funeral march) Backhaus’s tempo is right but the mood is too glib. True, he gives the music a certain amount of punch, but here it sounds lively and happy, not the least bit funereal. The last movement, almost predictably, is excellent.

We end with the sonata that comes just before the “Moonlight,” op. 27 No. 1. By this point, Beethoven was moving away from the more classical structure and style of the early sonatas and working his way toward not only a grander but more impassioned form of expression. In this respect, Backhaus’s performance of Sonata No. 13 is good but does not explore the undertow of the music. Even John O’Conor, whose Beethoven cycle is resolutely lyrical in approach, draws more out of this music than Backhaus does here, and I won’t even make the obviously unfair comparison with Schnabel. The bottom line: What was a good Beethoven sonata cycle in its day has not worn its uneven approach well. If you want a lyrical sonata cycle, you can buy O’Conor in digital stereo. If you want a dynamic and individual approach, you can try Sheppard. If you want the most consistent musical approach to all 32 sonatas, however, you must get either Schnabel or Fischer, and Fischer has the edge in both sonics and technical security.

Lynn René Bayley

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:1 (Sept/Oct 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.