This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

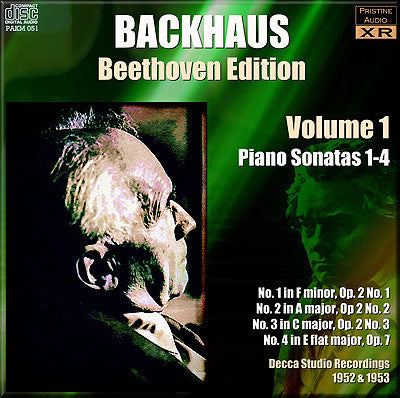

Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle begins here

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

Wilhelm Backhaus's first Beethoven Piano Sonata cycle, recorded between 1950 and 1953, was one of the first for the Long Playing record, and may well have been the first of several contemporary accounts to reach completion. Backhaus was already considered, as the review above points out, a "veteran" pianist, yet later that same decade he started the sonatas all over again, once more for Decca, this time in stereo, a cycle which he almost completed prior to his death in 1969, leaving only the Hammerklavier not re-recorded.

The existence of the stereo cycle has led to this mono cycle, which a number of listeners consider the better of the two, to be neglected by Decca - outside of Japan and a very limited Italian issue, it has never been reissued by the company. Sonically there's no doubt that the later recordings improved considerably over these early 50s mono versions, but there's much that can now be achieved in improving considerably the sound quality of these recordings, as well as correcting the "slight mechanical erraticisms of pitch and surface-hum" referred to in the review above.

In making these historic recordings, from one of the greatest of Beethoven interpreters, available again in fine-sounding 32-bit XR remasters, collectors can at last and with ease determine their own preferences with regard to the Backhaus discography.

Finally a note about pitch: The recordings so far analysed suggest some wayward tape speeds, resulting in pianos pitched variously at between A=432 and A=444, as well as some notable pitch changes, both sudden and sliding, during movements within recordings. One later recording in the series (to be released as part of Volume Three) includes what I take to be a "sticky edit", causing the pitch to lurch alarmingly (at one point it drops more than a semitone) over the course of several notes before steadying itself. Previously just about unfixable, these problems have all been resolved and the pitch of each recording standardised to A=440.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 2 No. 1

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2902

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 2 No. 2

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2920

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 3 in C major, Op. 2 No. 3

Recorded May 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2747

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 4 in E flat major, Op. 7

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2809

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

The Backhaus Beethoven Edition

(A Pristine Classical newsletter editorial by Andrew Rose)

A few weeks ago I was trawling through the thousands of

records here at Pristine, looking for inspiration, and out of curiousity

dug out a box set of Backhaus's Beethoven sonata recordings. A quick

flick through them revealed that although the majority would be off

limits due to their recording dates, a handful had fallen into the

public domain. But would I be able to bring anything to them?

I

started with a couple of test transfers and they sounded promising.

Certainly they seemed to have potential. But what a shame the entire set

wasn't ever going to be possible, as a result of the changes in

European copyright law due to take effect in the next year or two.

Of course there was the earlier, mono collection - which might indeed

hold more promise of remastering improvements. I decided to check when

Decca had last reissued them so that I could download a few samples from

iTunes. I searched and searched, but they were nowhere to be found.

So I started doing some serious digging around, scouring discographies

and old Internet discussions on the subject, and was astonished to find

that, despite some people swearing by them as the better of the two

cycles from Backhaus - and the only complete one, as he died before the

final recording of his stereo cycle could be made - there had been no CD

issue outside of Japan and an exceptionally rare Italian issue (which,

confusingly, had the same catalogue number as the stereo cycle, leading

me to wonder whether the Italian release was in error).

I

suppose this isn't entirely unusual. We've remastered a number of mono

Mercury recordings over the last couple of years which have been passed

over by the company themselves in favour of reissuing their stereo back

catalogue. A lot of recordings fell into a bit of a mono "black hole" in

the early-to-mid 1950s, and surprising as it seems for such an

important release - possibly the first complete Beethoven sonata cycle

of what you might call the "hi-fi" age - Backhaus's only truly complete

cycle is one of them.

The recordings were all made in Victoria

Hall, Geneva, Switzerland. They began in July 1950 (Nos. 12, 21, 30),

with the first six recordings being issued both on 78s and LPs, before

dropping the 78rpm releases for the third batch of recordings, made in

April and May 1952.

And what a marathon that proved to be -

Backhaus set down 11 of the sonatas during those sessions. Possibly this

was too much for him, as he returned to Victoria Hall six months later

to re-record three of them.

Sadly, in no cases does the

archive indicate precise recording dates. We know for sure that the

majority, quite possibly all, were produced by Victor Olof, with either

Arthur Haddy or Gil Went engineering, where this was noted. Went was at

the controls for the final sessions, the most gruelling of the lot, in

November 1953, when fourteen of the thiry-two were recorded, yielding

some five LPs which were released during the course of 1954. Perhaps by

this stage Decca had got wind of Wilhelm Kempff's DG series and wanted

to get to the end first...

Ironically, the next entry in

Decca's Geneva recordings discography after this mammoth session, which

took place in May 1954, bears the following prefix: "These were Decca's

first stereo recordings". What a shame for Backhaus, who'd be going

through the whole thing again a very few short years later - and already

well into his mid-seventies.

I'm pleased to report that a

stereo recording was made of Backhaus's Diabelli Variations of October

1954, also the case of course for his 1958-59 Vienna recordings of the

five concertos with Schmidt-Isserstedt. We hope to turn to these once

the present sonata cycle is complete, but I'm also interested in the

mono concerto recordings. Curiously here Backhaus recorded all five for

Decca in 1950-53 with the Vienna Philharmonic under variously Krauss and

Böhm, but the First was never issued. (I would make clear that in my

Decca discography it doesn't appear even as an unreleased item, but my

Backhaus discography states a recording of the First Concerto was made

in April 1951 by Decca and remains unissued.)

So what do we

make of the earlier sonata recordings. Well I'm going to reserve comment

on performances because (a) I've not heard them all, and (b) there are

far better experts than myself who will no doubt pass judgement in due

course. Contemporary reviewers' reactions in many way mirror those for

the Schnabel series twenty years earlier - a mixture of rapturous

approval and some quite pointed criticism. Whether the years since their

recording have changed opinions generally or specifically remains to be

seen. Backhaus certainly had heritage and was already a seasoned

"veteran" performer (to quote from a Gramophone reviewer) by the time he

began the first cycle, at the age of 64.

Technically there are

few surprises. The sound quality Decca achieved in its Geneva

recordings of this period has never particularly excited me - they're

just not on a par with what they were capable of in London at the time -

but they're adequate as far as the early years of high fidelity tape

are concerned. They've certainly benefited from a good dusting off with

XR remastering putting some real life back into the rather dull, dusty

originals, but it's been a constant battle against hiss to do so.

Pitch also has proved erratic. On one movement of the first four

sonatas I spotted a clear change of pitch midway through, as a result of

a tape edit. Elsewhere another bad edit meant the same note was

effectively struck twice. All of this is correctable today, as is the

wobbliness of pitch in the Third Sonata, and the wide variation of

tuning frequencies heard across the sonatas - of those analysed so far

I've seen them range from A=433 up to A=444, something which seems more

likely to be caused by slight inaccuracies in tape record and replay

speeds than the piano itself. For the sake of argument I'm adjusting

them all to A=440 and leaving them there.

Thanks to a

combination of tempi and choices of repeats, we should be able to get

all 32 sonatas, in order, onto 8 CDs rather than the 10 of the Schnabel

series. Thereafter we'll see what we can do with the rest of the

recordings - concertos and variations - that Backhaus made during this

era, ultimately making up a set which includes all five concertos, all

32 sonatas and the Diabelli Variations.

Andrew Rose, February 3, 2012

Fanfare Review

I found myself charmed by his conception of these early sonatas

When I was growing up in the early 1960s, Wilhelm Backhaus was generally known as a finely chiseled but somewhat lightweight pianist, best suited to the music of Chopin and Mozart. Thus it was a considerable surprise when he recorded an exciting, beautifully shaped performance of the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 with Karl Böhm conducting; even critics with a longstanding antipathy toward Backhaus raved about that recording, and with good reason.

Because of this, I decided to consider reviewing CD 1 of Pristine’s restoration of the pianist’s early mono Beethoven cycle. Sonata No. 3 was recorded in 1952, the others on this disc in November 1953. Restoration engineer and annotator Andrew Rose indicates that the original recordings, despite having been made by a major label, were beset with technical problems. In addition to those mentioned in a contemporary review of one of the LPs—“the tone sounds hard in the development section,” “slight mechanical erraticisms of pitch and surface-hum”—Rose also mentions “some wayward tape speeds, resulting in pianos pitched variously between A433 and A440.” Whether or not this was due to tape slippage when originally mastered, or actual differences in the pianos that Backhaus played (there were still, in Germany at that time, some instruments pitched below A440), Rose has consistently pitched all of the Backhaus recordings to our modern standard.

Without knowing what the rest of the series sounds like (this is my first hearing of these recordings), I can attest that Backhaus’s performances of the opp. 2 and 7 sonatas are, in general outline and feeling, very similar to the recordings of Irish pianist John O’Conor, with some differences. Those differences are a little more obvious ritards and rubato than that employed by O’Conor, with the result that some of the movements in these performances have a decidedly Old World feeling to them (one such example is at the 3:15 to 3:30 mark in the last movement of the First Sonata). On the other hand, Backhaus’s occasional “stop-and-listen-to-this” moments are not nearly as exaggerated as those of Wilhelm Kempff, whose Beethoven sonata cycle was all the rage in the 1960s.

Indeed, as this set of the first four sonatas proceeded to play, I found myself charmed by his conception of these early sonatas. My only caveat, as is the case with O’Conor’s cycle, is that Backhaus fails to make as much of the sharp dynamic contrasts written into the scores, which Artur Schnabel and Craig Sheppard bring out so well (Schnabel at the proper brisk tempos, Sheppard a shade slower). Thus the reader of this review is faced with a bit of dilemma. Does one really wish to start collecting this early Backhaus cycle? He did rerecord every sonata except the “Hammerklavier” in stereo for Decca, and that cycle is currently available as a boxed set. Rose indicates that many listeners consider this earlier, mono cycle to have been the better of the two. Yet if you have part, or all, of the Schnabel cycle (I particularly recommend his reading of the early sonatas, at least 1–12 plus the op. 49, which was written earlier) and either the complete O’Conor or Sheppard cycles, you may not feel a pressing need for Backhaus. I don’t really know how the later discs of this series will play out, but I will say this: If his performances of the “Pathétique,” “Waldstein,” “Appassionata,” “Les Adieux,” and, yes, even the “Hammerklavier,” not to mention all the important sonatas in between, are as good as his stereo recording of the Brahms Concerto No. 2, you may want to opt for Backhaus in your collection. I, for one, will be looking for the further issues in this series in order to make my determination.

Lynn René Bayley

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:6 (July/Aug 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.