This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Contemporary Reviews

- Sleevenotes

This Metropolitan Opera broadcast has been very well preserved in an excellent taped recording. Beyond a general tweaking of the overall sound and some very mild noise reduction my interventions were few and far between, with just some occasional dropouts and crosstalk to deal with, along with a rather bronchial winter's audience. My source omitted some of Milton Cross's commentaries and as such I've been forced to edit or fade these as best I can whilst preserving a sense of occasion - as this incredible performance certainly was.

This new transfer, heard here in Ambient Stereo XR sound, offers the listener a fabulous window on the dawning at the Met of one of the great operatic careers of the second half of the twentieth century - just as another of a slightly earlier age, that of Nicola Moscona, finally comes to an end.

Andrew Rose

CD One

ACT 1

1. Prelude and Opening Chorus (7:37)

2. Cruda, funesta smania (6:00)

3. Regnava nel silenzio (13:01)

4. Sulla tomba che rinserra (12:28)

ACT 2

5. Lucia fra poco a te verrà (3:14)

6. Il pallor fuesto, orrendo (5:26)

6a. Soffriva nel pianto (7:05)

CD Two

8. Per poco fra le tenebre (3:24)

9. Chi mi frena in tal momento (8:27)

10. T'allontana, sciagurato (5:02)

ACT 3

12. D'immenso giubilo (1:45)

13. Dalle stanze, ove Lucia (5:24)

14. Alfin son tua (12:28)

15. Spargi d'amaro pianto (5:39)

16. Fra poco a me ricovero (8:07)

16a. Oh, meschina! oh, fato orrendo! (8:58)

Radio Ending - Milton Cross (1:32)

CAST

Lucia.....................Joan Sutherland

Edgardo................Richard Tucker

Enrico...................Frank Guarrera

Raimondo.............Nicola Moscona [Last performance]

Normanno............Robert Nagy

Alisa....................Thelma Votipka

Arturo..................Charles Anthony

METROPOLITAN OPERA ORCHESTRA AND CHORUS

Conductor..............Silvio Varviso

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

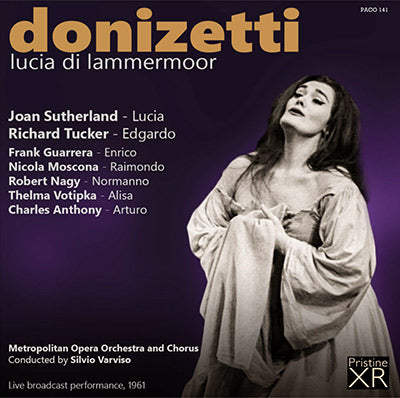

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Joan Sutherland as Lucia in this production

Recorded 9 December 1961

Metropolitan Opera, New York

Total duration: 1hr 55:34

Review of Irving Kolodin in The Saturday Review:

JOAN SUTHERLAND came, sang, and conquered the Metropolitan Opera House in her awaited debut as Lucia. This mode of putting it means there was never much doubt of her ability to deliver Donizetti's music with distinction. But how it would sound in a theatre that has devoured many another famous voice was something else. This, however, was quickly determined after her entrance aria in the Fountain Scene: broad, fluent, perfectly in pitch, fastidious in style, a treat to the ear and an incitement to the enthusiasm of an audience that filled every saleable spot.

Thereafter it was a matter of sitting back to enjoy a superlative demonstration of vocalism by a grand mistress of the ancient, ever new art. As she developed the part, through the duet with Edgardo, the angry episode with her brother, into the sextet, the accumulating evidence pointed to one thing in particular: this is a voice consistent in timbre through two octaves (E flat to E flat in this part) with scarcely a break-full, ringing, and clear at the top, solid in the middle, viola-mellow at the bottom.

Her "Mad Scene" was a thoroughly studied thing in itself, altogether suited in character to what had preceded, but sufficiently illuminated by highlights to be the shining climax to the whole. Here she allowed herself more freedom in ornamentation than previously, working out delicate traceries of figuration in and around the melodic line, stitching in a bit of petit-point staccato, coasting cleanly down a descending scale, and finally demonstrating her prize beyond price-a perfectly controlled trill that was not a mere glorified vibrato but a swift, even beat of two notes perfectly interchanged. Finally? Not quite. She ended her evening's work with a bright, firm, fully produced high E flat that is still ringing in the ear as this is written.

So much for the unquestionable. What of the questionable? Not her musicianship, certainly, which is near faultless, nor her stage deportment, which is serious, considerate of her associates, and more modest that that of most with a tenth of her accomplishments.

When it comes to character portrayal, however, Miss Sutherland has work to do. Prior to the "Mad Scene," she projected Lucia as a maid all sad of mien, cast over with a sense of tragedy to come, with a mid-century (nineteenth) slant of the body to compose her tall figure in an angular attitude of "suffering." For the "Mad Scene." she wore her auburn hair at shoulder length and a faraway look that searched out the cleverly contrived action (probably the influence of Franco Zefferelli, who directed her at Covent Garden) to fill in musical gaps with pantomime and movement. One especially apt incident accompanied an echo effect in the music, in which she turned her back to the audience, apparently listening (to herself). But all the artifice did not generate compulsion, develop conviction, or magnetize the observer into involvement with anything but vocal virtuosity. There is so much of this, however, that one could only say: Well done and welcome, Miss Sutherland; may your prime be long and productive.

In the old-fashioned way, her entrance was accompanied, physically as well as musically, by her own conductor, the young Swiss Italian Silvio Varviso. There is nothing in the least old-fashioned about his treatment of the score, except a virtuous attention to detail, a well-discriminated distribution of emphasis between pit and stage. Richard Tucker sang well, sometimes brilliantly, as Edgardo, while indulging some petty tenoristic privileges in costuming and action; but Lorenzo Testi's blatantly overstressed Ashton did not belong on the same stage with Sutherland (or Tucker).

Review of Robert J. Landry in Variety

Joan Sutherland's Met Debut Teases Memory" Maybe Nothing Ever Like It

The Metropolitan Opera season, which was almost cancelled, has produced the debut of a soprano, Joan Sutherland, of Australia, who is almost unimaginably good. Resultantly, the Sunday (26) night audience went nearly berserk with delight during and after the climaxing mad scene in "Lucia de Lammermoor." Although explosions of enthusiasm are familiar enough, though never common, at the Met nothing comparable is recalled in recent times. There wasn't applause but wild beatings of palms; not bravos but roars of exultant appreciation. There were 10 genuine, unforced, prolonged solo curtain calls. At the sixth the examples of a few who were standing became the complete audience.

Suffice that with this Australian's arrival a box-office sensation, a queen among divas and opera history were all made simultaneously. It was simply not possible to find anything to quibble about. Even the creaky old libretto suddenly seemed exciting.

That the audience anticipated itself was clear when they broke into her first entrance, a practice frowned on at the house and destructive of illusion and mood. Actually the Australian has sung many times in U.S. concert and her London label disks have established the amazing richness of her voice, especially in the top range, which in "Lucia" included a smashing, full-throated high E. Her performance all the way, the trills and flawless production of rounded tones gave new pulsation to an opera which is frequently more hokum than art.

In the presence of this kind of soprano all the other singers assumed fresh interest. Richard Tucker sang his head off, Lorenzo Testi was excellent as the tyrannical brother. As for the sextet it had a powerhouse impact. The evening contained the further interest of including a new youthful conductor from Switzerland, Silvio Varviso. He made a very good impression indeed.

No point in complicating the simple fact of a once-in-a-generation eruption of performing genius. Miss Sutherland, tall, completely the mistress of her role, and pretty good actress to boot, was that rara avis, a promised glory that exceeded hopes. She is the kind of talent that old-timers often refuse to believe any longer lives.

Review of Leighton Kerner in the Village Voice

MUSIC: JOAN SUTHERLAND

With her fifth Metropolitan Opera "Lucia di Lammermoor" on December 21, Joan Sutherland fulfilled her final New York performance commitment for the season and left those who had heard her with nothing to do but gasp at the memory of what they had heard.

This bedazzlement in retrospect was not only accounted for by the "Lucias," but extended' also to a December 5 concert performance in Carnegie Hall of Bellini's "La Sonnambula," perhaps even farther back to last October 7, when a few hundred fortunates were able to get into the rather small Rogers Auditorium at the Metropolitan Museum to hear the tall, redheaded Australian sing three arias from Handel's "Alcina," and, inevitably, all the way to last February, when she made her New York debut in Bellini's "Beatrice di Tenda" at Town Hall.

Vocal Rocketry

The concert performances of the two Bellini operas and of the Handel excerpts contributed to what became a familiar image of this "prima donna assoluta": Visually, an attitude of utmost composure, with head and shoulders often set at an angle to the rest of the body, perhaps to minimize her height; aurally, a gradual conflagration of trills within turns within roulades within scales, reaching, in the final moments and in the half-octave above high C, a combination of power, brilliance, and agility not approached within a mile by any singer known to this or the preceding generation. With regard to the aural image, the culmination came in the two arias of the final scene of "Sonnambula," with the long soft spun phrases of "Ah! non credea mirarti" (reminding more than one listener of Claudia Muzio) and with the astounding speed at which Miss Sutherland took the runs, 10-note skips, and other vocal rocketry in the "Ah! Non giunge" rondo.

In Donizetti's "Lucia;" on a theatre stage, the image underwent some changes here and there. As an actress Miss Sutherland has not the instinct of a Callas, but she does seem to have the intelligence to follow good stage direction - in this case, not that of the Met's Desire Defrere, who always has got stuck with the most dog-eared part of the repertory, but the direction of Franco Zeffirelli, who coached Miss Sutherland in the part at Covent Garden. Perhaps Mr. Zeffirelli was pressed for time, for once in a while the lady resorts to some pretty awkward walks around the furniture.

Mad Scene

In the "Mad Scene," however, comes a musico-dramatic display such as, perhaps, not even Donizetti dreamed of. In the first aria of the scene, "Alfin son tua," the dashing about and crouching in corners seems to be the incarnation of the Ophelia we have all wanted to see on a stage. The broken recitatives and snatches of melodic reminiscence take on sudden power. The notorious vocal cadenza with flute accompaniment, heretofore, the silliest musical passage ever penned, now becomes lightening flashes of hallucination. Lucia seems to chase the flute sounds in every direction with vocal imitations that take on an increasing bravura. She hears one flute roulade from the general direction of the opera house's Grand Tier, and back it flashes from her throat. The next is a salvo at the top balcony. The third she delivers with her back to the audience, and it bounces from the rear of the stage back into the auditorium with thrilling and uncanny clarity. Then, finally, her slow, ecstatic reprise of the First Act duet, with the flute sounds circling dizzily in the background. Going into the second aria, "Spargi d'amaro pianto," ending with a fortissimo top E-flat that hits the listener like an arrow, and that, ladies and gentlemen, is the "Lucia " "Mad Scene" in what will be the Sutherland tradition.

One wonders what the radio audience, listening to this broadcast of Lucia di Lammermoor, made of it all. Lucia was by far the most popular of the bel canto operas at the Met and it featured regularly in the broadcast schedules. Between 1932 and 1956 audiences would have heard the light and agile voice of French soprano Lily Pons in the title role 14 times (and on 3 occasions, the equally light American soprano Patrice Munsel), but in December 1956 Maria Callas assumed the role, in her only Met broadcast. Callas was a completely different singer to Pons, and was important in bringing bel canto operas into the mainstream of many of the world’s opera houses. If Pons brought light virtuosity to the role of Lucia, Callas brought dramatic intensity, even if occasionally at the expense of accurate coloratura. Joan Sutherland brought something completely new, the power and stamina of a helden-soprano, which she combined with spectacularly accurate and dazzling coloratura.

Joan Sutherland started her career at Covent Garden singing roles such as Amelia, Desdemona and Eva and she could reasonably have been expected to graduate, as she matured, to the heavier Wagnerian roles. Instead her career took a left turn as her husband, conductor and musicologist Richard Bonynge, persuaded her to make the bel canto repertoire her own. She sang Handel’s Samson at Covent Garden in late 1958, and followed this with a sensational run of performances as Lucia in early 1959. Most commentators agreed that this was her break-through moment, when she went from being one amongst many (remember she would have been competing for Wagnerian roles with the likes of Birgit Nilsson and Astrid Varnay), into a league of her own. It was not long before she was in demand around the world, and the Italian press dubbed her ‘La Stupenda.’ Her Met debut did not occur until 1961 and this broadcast is one of only five performances (all as Lucia) in her debut season. The press were bowled over, ‘a superlative demonstration of vocalism’ said one, ‘unimaginably good’ said another. If the applause following the Mad Scene is any indication, the audience in the house were equally impressed. A voice the size of Sutherland’s carried easily to every seat in the Old Met.

Joan Sutherland would return frequently to the Met until 1987 and not only in bel canto operas such as Norma, La Fille du Régiment and I Puritani (these last two opposite Luciano Pavarotti, a frequent collaborator), but also asDonna Anna in Don Giovanni, all four female leads inLes Contes d’Hoffmann (opposite Plácido Domingo), and Leonora in Il Trovatore (again opposite Pavarotti).

Sutherland is partnered by American tenor Richard Tucker, halfway through a near thirty year Met career. Tucker was a wonderfully versatile tenor that managements can only dream of. He could sing heavier roles such as Don José, Andrea Chénier, and Hoffmann, as well as lighter ones such as Rodolfo, the Duke of Mantua, and Ferrando. He first sang Edgardo in 1949, and it was the only complete opera where he partnered Sutherland, apart from a single La Traviata in 1964. This is the first of two broadcasts of the pair of them in this opera. Tucker has more vocal weight than many Edgardos, and this makes him an ideal partner for Sutherland.

American lyric baritone Frank Guarerra sings Enrico. Guarerra had a long Met career between 1948 and 1976 singing a wide variety of roles such as Escamillo, Amonasro, Valentin and Germont. Greek bass Nicola Moscona sings Raimondo in his final Met performance, bringing an end to a distinguished career that began in 1937.

The performance is conducted by Swiss maestro Silvio Varviso. Varviso was a regular at the Met in the 1960s, but had only made his Met debut alongside Sutherland in Lucia a few weeks before this broadcast.

Fanfare Review

for the sheer electricity that only a live performance can provide, it’s the 1961 Met broadcast I turn to ... I promise you will not be disappointed

On November 26, 1961, the legendary soprano Joan Sutherland made her triumphant Metropolitan Opera debut in the title role of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. On December 9, Sutherland reprised the role for the Met’s weekly Saturday afternoon broadcast. Prior to Sutherland’s arrival at the Met, Lucia had been the province of such sopranos as Lily Pons, Patrice Munsel, Roberta Peters, and Mattiwilda Dobbs. All were considerable artists to be sure, and possessing the type of high leggero voice typically associated with Donizetti’s Lucia. Yes, Maria Callas did bring her interpretive genius and substantial voice to the role at the Met, but for only seven performances, spanning 1956–58. Both contemporary reviews, and a recording of the December 8, 1956 Met broadcast (I reviewed an Immortal Performances release in the March/April 2017 Fanfare, 40:4) indicate that Callas was not in her best form on those occasions. This background set the stage for Joan Sutherland, in her absolute prime, possessing a voice of considerable beauty and dramatic weight, aligned with a technique that allowed her to dispatch Lucia’s spellbinding coloratura, trills, and stratospheric high notes with breathtaking confidence and ease. The result, as documented in the December 9, 1961 broadcast, was pandemonium, the stuff of legend. It is true that even at this relatively early stage of her career, Sutherland’s diction lacked ideal clarity, and the dramatic approach is a rather generalized one, especially set aside such Lucias as Callas and Beverly Sills. But Sutherland certainly understands Lucia’s character and her predicament, and sings with such technical mastery as to make her assumption of the role required listening for all who care about the art of great vocalism.

The December 9, 1961 Lucia broadcast would be a must, even if the remainder of the cast was second-tier. But on this occasion, there are other stars as well. The Edgardo, Richard Tucker, is likewise in prime form. Tucker made his Met debut in 1945, the start of a career that would last almost 30 years. Over time, Tucker’s lyric voice took on weight and brilliance. By the time of this Lucia broadcast, Tucker had added to his repertoire such roles as Des Grieux in Puccini’s Manon Lescaut, Don Alvaro in Verdi’s La forza del destino, and the title role in Giordano’s Andrea Chénier. It is true Edgardo is often sung by lyric tenors, and to great effect. But for me, the ideal Edgardo combines bel canto technique and sensibility with a voice capable of powerful authority for the wedding scene and the great concluding Tomb Scene. The first Edgardo after all, was Gilbert Louis Duprez, a tenor known for his intensity of declamation and ringing high notes. On this occasion, Tucker finds an ideal balance between bel canto elegance and dramatic fire. Tucker, like Sutherland, possessed a masterfully assured technique that allowed him to give his greatest performances when the spotlight burned brightest. This Lucia broadcast is such an occasion.

The other superb contribution to the broadcast is from conductor Silvio Varviso, leading a performance brimming with precision and energy, but also sensitivity and tenderness where appropriate. Sad to say, Frank Guarrera, a valuable and reliable Met baritone for many years, is not in good vocal form. He certainly depicts Enrico’s malevolent, bullying character, but there is little elegance, beauty, or nuance to be found on this occasion. Nicola Moscona, singing his Met farewell after a long and important career, acquits himself admirably. The inclusion of some of Milton Cross’s broadcast commentary adds to the sense of occasion. The recorded sound of the new Pristine Audio reissue is superb, allowing you to hear this great event in all its glory. The liner notes include an essay by producer Andrew Rose. No texts or translations are provided. If you don’t own this Lucia broadcast, please acquire it, posthaste.

I wish I could be as enthusiastic about the Met’s 1954 studio recording, originally made for Columbia, and now receiving its first official CD reissue, courtesy of Sony Classical. The French soprano Lily Pons made her Met debut as Lucia on January 3, 1931 and over the next quarter century or so gave almost 100 performances in the role. Several Met broadcasts from the 1940s document an interpretation that, independent of Pons’s captivating stage presence, she possessed considerable charm, vocal beauty, and brilliance. But by the time of the 1954 studio recording, Pons was nearing her 56th birthday, and the end of her career. The middle voice lacks its former security and purity. Matters improve as the music ascends, but overall, the performance lacks energy, an impression no doubt exacerbated by Fausto Cleva’s leaden conducting. Several recordings, both studio and in-performance, demonstrate Cleva was capable of far better. Tucker is again the Edgardo, and in fine voice, but he too seems dragged down by the overall lack of energy. Guarrera is in much better form than for the 1961 Met broadcast. Raimondo can be a faceless role, and Norman Scott does little to elevate it beyond that. The recorded sound is quite fine mid-1950s mono (the back of the CD box lists it as stereo). The only reason I can see to purchase this set would be for Tucker’s Edgardo, but the 1961 broadcast showcases him to far better effect. For Pons’s Lucia, look to the earlier Met broadcasts.

One footnote must be added about the stage cuts, standard for the time, employed in both of these recordings. Unlike some other operas, the cuts to Lucia extend beyond excision of repeats and bridge passions. They comprise entire scenes, including the Lucia-Raimondo duet preceding the wedding scene and the Edgardo-Enrico confrontation that follows. This music deserves to be heard, and so at least one complete recording of Lucia should be a cornerstone of any representative opera collection. Either of Sutherland’s studio versions for Decca fits the bill quite nicely. The first, made in 1961, captures Sutherland in amazing prime voice, and also includes Robert Merrill at the top of his game as Enrico and the great Cesare Siepi as Raimondo. A decade later, Sutherland once again recorded the opera, this time with Sherrill Milnes as Enrico and Nicolai Ghiaurov as Raimondo. The Edgardo is Luciano Pavarotti, in his finest voice and form. Enough said. If Sutherland isn’t quite as spectacular here as a decade earlier, that is measuring the artist by her own extraordinary standards. I own both recordings, and no one is taking either away from me. But for the sheer electricity that only a live performance can provide, it’s the 1961 Met broadcast I turn to most often. Give it a try. I promise you will not be disappointed. Ken Meltzer