This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Artwork

- NY Times

Kathleen Ferrier's American debut at Carnegie Hall, 1948

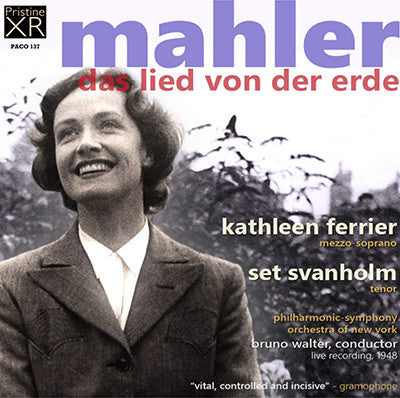

“Vital, controlled and incisive” - GRAMOPHONE

This recording of Kathleen Ferrier's American debut first appeared on CD in 1999, when two different CD releases almost coincided. Both are now harder to come by. It was partly this and partly a desire to address the shortcomings of a "privately made recording on acetates" (Gramophone) which led to a request for me to see what might be done using today's digital restoration technology.

After removing a great deal of surface noise and hiss I've been able to make great strides with the overall tonal quality, improving greatly the clarity of vocal delivery and ameliorating congestion in the lower orchestral ranges. I've also been able to both correct overall pitch and address problems with wow and pitch drift which were beyond the technologies of the late 1990s.

The result is a highly memorable and enjoyable Das Lied - one can only assume that the three days that elapsed between the first performance, reviewed with some reservations expressed in the New York Times (above), and the present one made all the difference with regard to both performances and delivery.

Andrew Rose

-

MAHLER Das Lied von der Erde

Live at Carnegie Hall, New York, 18th January 1948

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Kathleen Ferrier

Total duration: 58:20

Kathleen Ferrier - mezzo-soprano

Set Svanholm - tenor

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York

Bruno Walter, conductor

CONTEMPORARY PRESS REVIEW: FIRST NIGHT

WALTER CONDUCTS MAHLER SYMPHONY

As Guest on Philharmonic's Podium He Features 'Das Lied von der Erde’ Work

By OLIN DOWNES

We have always preferred '‘Das Lied von der Erde” to all other of the symphonic works of Gustav Mahler. Bruno Walter specializes in Mahler. He signalized his return to the podium of the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra last night in Carnegie Hall with this particular composition, which he prefaced with a delightfully gemuetlich reading of the Beethoven Fourth Symphony.

In the simplest and profoundest pages of the Fourth Symphony, which are those of the introduction and the slow movement, the conductor went somewhat faster than is customary. Both movements are marked adagio — very slow. But all tempo directions are relative, and the relativities include the feeling and the taste of the musician interpreting. For some a more deliberately poised tempo in the places mentioned gives the music a more mysterious heauty. Mr. Walter’s tempi had the pulse of the flesh as well as the spirit. The symphony delighted the audience by its humor, its play of fancy, its perfection of ideas and of form. A triumph for the players and the conductor! For the listener an altogether delectable experience!

One’s reasons for admiring the “Lied von der Erde” are doubtless generally shared. The lyricism of the poetry has an inspired parallel in the completely lyrical nature of the scoring both for voices and orchestra. Tenor and contralto — last evening the mezzo-soprano, Kathleen Ferrier — carry the burden of the song. But the orchestra also, with its remarkable devices of coloring and of dramatic accentuation, sings its song, and intersperses the final verses for the woman's voice with an interlude which is a “lied” of its own. The very melodic writing needs no translation or commentary to exert its immediate if sometimes obvious and sentimental appeal. Sentimental or not, the complete sincerity of the music is unquestionable and affecting.

Saying this, one adds reluctantly that the performance, for one reason or another, began to fall before it was over. This at least was the reaction of one listener who is not a perfect Mahlerite. Was this only due to certain characteristics of the performance? Both soloists were deficient in diction. Svanholm, the tenor, could only shout, in the opening verses, against heavy orchestra, and in this Mr. Walter did not spare him.

But Mr. Svanholm was prevailingly hard-voiced and lacking in variety of tone color. Miss Ferrier had but recently emerged from a bad cold. Her voice became freer as she went on. She could not, however, give the full significance to her text and music. Some time before the end was reached “Lied von der Erde” was becoming langweiling, lachrymose, old-fashioned.

NEW YORK TIMES, 16 January 1948

Fanfare Reviews

Strongly recommended to all aficionados of historic performances and of great singers and conductors

Back in issue 37:4, when I reviewed Pristine Audio’s remastering of Bruno Walter’s 1960 studio account of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, I discussed in some detail Walter’s discography of either eight or nine surviving accounts (the genuineness and exact dating of a purported 1952 Vienna performance being in dispute). Readers interested in the nitty-gritty details may consult that review in the Fanfare Archive. Here we have a remastering of a historic occasion: Kathleen Ferrier’s American debut. This performance previously enjoyed two issues: one by Naxos in a restoration by Richard Caniell from 1999, and the other in a 10-CD commemorative set of historic live Mahler recordings issued by the New York Philharmonic in late 1998. Doubtless the NYPO had access to a much superior source, for its version has much better sound than the rather muffled Naxos issue and Caniell has a justly earned reputation for exemplary remasterings. Both issues are now out of print, and the NYPO one was never available separately in any case (used copies of the set are fetching over $100 on Amazon). In this case, Andrew Rose appears to have started from the New York Philharmonic issue and employed his trademark XR remastering process upon that. The improvement in sound quality is definite if minimal, resulting in greater clarity in more congested passages. More importantly, it restores this performance to the active catalog as a separate and quite affordable release. While the sound cannot compare to the superb sonics of Decca’s 1952 studio account (also remastered by Pristine, a version I have not heard), it is certainly quite listenable and affords far more detail than one might expect from a live broadcast of its vintage.

Most importantly of all, how good is the performance, and how does it compare with its rivals in the Walter discography? The answers respectively are very good and very well. Bruno Walter of course had an unrivaled identification with the score, having given its world premiere after Mahler’s death, and his three commercial recordings (1936 live, 1952, and 1960) remain dominant reference points in the Mahler discography despite their age. A particularly noteworthy factor is a greater degree of urgency in Walter’s conducting as compared to his justly fabled 1952 studio account. The differences in the timings may not seem substantial, but bear in mind that those from 1948 also include about 10 seconds of audience noise between each movement, so that a variance of about 30 seconds in a movement of four to eight minutes length is one of 15 percent to 7 percent, which is quite perceptible.

| Movement | 1948 | 1952 |

| 1 | 8:19 | 8:38 |

| 2 | 8:50 | 9:14 |

| 3 | 3:04 | 2:59 |

| 4 | 6:18 | 6:45 |

| 5 | 4:12 | 4:24 |

| 6 | 27:37 | 28:22 |

Having previously played the First, Second, Fourth, and Fifth Symphonies of Mahler under Walter’s baton (and of course that of Mahler himself four decades before), the New York Philharmonic by this time was one of the very few well seasoned Mahler orchestras in the world, and its playing here is thoroughly idiomatic. As for the soloists, the legendary and much lamented Kathleen Ferrier is so famed for her 1952 studio recording of Walter in this same part that for me to expatiate upon her extraordinary and unique voice would be to gild the lily and try the patience of most readers. She is simply marvelous here, though her 1952 accounts, sung sub specie mortis in her ongoing losing fight against cancer, have both manifold subtle nuances and a heartbreaking pathos that she had yet to achieve at this stage of her career; here she is still a young lady full of life, contemplating tragedy from the greater remove of a sensitive but objective observer rather than the harrowing internal perspective of a suffering victim. The difference is most telling in the final bars of “Der Abschied”; here it closes with serene acceptance, while the Vienna account draws out the final measures with desperate reluctance to bid farewell to all things lovely.

As for tenor Set Svanholm, while he has his admirers, I have generally not been among them, usually finding his voice rather leathery, lacking in warmth and plasticity. Here, however, at an earlier stage in his career, he is in good form and for me a surprisingly welcome asset. (The subsequent 1953 broadcast performance with Walter, Elena Nikolaidi, and the NYPO finds him in markedly poorer form.) His voice is powerful and steady (an occasional slightly quavery note aside), and he soars over Mahler’s orchestral tuttis without difficulty. His interpretation is impetuous and forceful, a touch too much so in a few syllables that are punched out overly hard, but aside from Jonas Kaufmann it’s hard to think of anyone today who could exceed or match him in this part. Perhaps the greatest interest lies in the polar contrast he presents to Julius Patzak in the latter’s 1952 performances with Walter. Largely self-taught in vocal technique (he originally studied conducting), Patzak had one of the most idiosyncratic voices of any singer to achieve a major reputation. Its relatively light weight (the Evangelist in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion was one of his most frequent roles, though he unexpectedly achieved great fame as Florestan in Beethoven’s Fidelio) and extreme nasality would seem a poor fit for Mahler’s orchestral perorations; but Patzak possessed incredible finesse and could thread the finest vocal needles with astounding elegance, and his ironically world-weary rendition of this part remains an unsurpassed interpretive benchmark. Whereas vocally Svanholm wields a weighty cutlass, Patzak deftly employs a stiletto.

In sum, anyone looking to have only one representative recording of Mahler’s late masterwork under the baton of his closest colleague and foremost disciple will naturally gravitate to the 1952 studio version, or possibly its 1960 stereo successor available from either Sony or Pristine. Ditto for anyone seeking just one version of Das Lied with Ferrier. But for those desiring additional perspectives on these two artists, and/or anyone wanting to hear Svanholm (or simply a more heroic tenor than Patzak), this release commands attention, and hearty thanks are due to Andrew Rose for making it available again. Strongly recommended to all aficionados of historic performances and of great singers and conductors.

James A. Altena

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:3 (Jan/Feb 2017) of Fanfare Magazine.

This recording is a digital restoration of a 1999 release of this performance. Andrew Rose, the engineer of the current release, writes that present day technology has allowed him to remove “a great deal of surface noise and hiss” and to “make great strides with the overall tonal quality, improving greatly the clarity of vocal delivery and ameliorating congestion in the lower orchestral ranges.” The balance between upper and lower registers is markedly superior in this restoration. However, there is a tradeoff. Whereas the chromatic trumpet declamation toward the beginning of “Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde” is rather pale and far overshadowed by the horn in the 1999 release, it is a bit strident in the current restoration, and the rush of winds accompanying it seems to overload the microphones in a cacophony of sound. This is an ongoing tradeoff: It is difficult to distinguish individual lines in louder, faster orchestral passages, which seem noisy and shrill. However, the gain in color in all other passages and the crispness of the vocal sound far outweigh this issue.

As for the performance, it is simply a must-have. Bruno Walter’s conducting is more impetuous here in comparison to the famous 1952 Vienna recording with Ferrier and Julius Patzak; his interpretation in the 1952 recording is perhaps more noble. Ferrier’s high notes (for example in the first phrase of “Der Einsame im Herbst” are a bit warbly here, with an over-rapid vibrato that is less apparent in the 1952 recording, and she goes slightly sharp at the climax of that movement, but her expressive power is unsurpassed in both recordings, and her variety of phrasing and articulation and her connection to the text may even be preferable here. The orchestra overpowers her a bit in the manic fast section of “Von der Schönheit” and her voice is overly prominent in the mix of “Der Abschied.” But in contrast to the 1999 release, there is no sense of sonic overload in the vocal line of “Der Abschied”; Ferrier’s voice has been returned to its characteristic warm richness here.

My one dissatisfaction with this performance is Set Svanholm’s delivery, which I find to be relentlessly declamatory. To be sure, the tenor movements call for a heroic sound. But Svanholm sings syllable by syllable in a near-constant marcato that provides little room for shading and multi-syllabic phrasing. The tone quality is glorious on long notes, which inherently have space to bloom. It is a naturally younger, brighter sound than Patzak’s, not simply due to their ages (44 for Svanholm, 54 for Patzak) at the time of their respective recordings. But even in rustic, boisterous passages, where such a sound is perhaps preferable to Patzak’s, Svanholm’s delivery is monotonously choppy. But I must emphasize: this is an indispensable recording, and I give it a very high recommendation. Myron Silberstein