- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

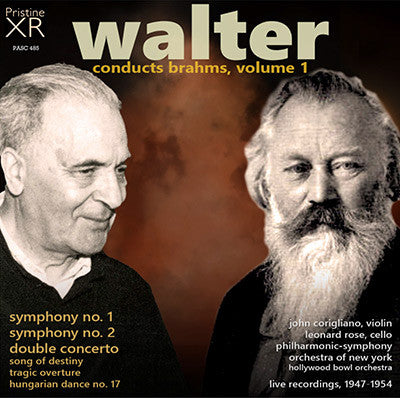

- Cover Art

Fanfare Review

“Highest possible recommendation” is simply not good enough here; this is beyond all praise

Although Bruno Walter is perhaps most immediately identified with Mahler and Mozart, Brahms was extremely dear to him, and in fact is the composer whose orchestral repertoire he most frequently recorded, proportionately speaking. With Columbia, he twice set down the four symphonies, the two overtures, the Haydn Variations, and the Double Concerto, originally in mono with the New York Philharmonic in 1951–54 and then a remake in stereo in 1959–60 with the West Coast incarnation of the Columbia Symphony Orchestra; the mono cycle also included four of the Hungarian Dances (Nos. 1, 3, 10, and 17). He also made pre-war 78-rpm recordings of the Academic Festival Overture and Symphonies Nos. 1 and 3 with the Vienna Philharmonic, and of No. 4 with the BBC Symphony. In addition, there are a 1954 mono recording of the German Requiem and a 1941 mono recording of the Schicksalslied (sung in English as the Song of Destiny) with the NYP, and 1961 stereo recordings of the Alto Rhapsody and Schicksalslied with the CSO. By way of comparison, the only works of Beethoven he recorded three times were the Violin Concerto, the Leonore Overture No. 3, the Symphony No. 6, and the finale of the Symphony No. 9; of Mozart, the Symphonies Nos. 38–41, the Eine kleine Nachtmusik, and the overtures to Così fan tutte, Le nozze di Figaro, and Die Zauberflöte. (The Symphony No. 41, Eine kleine Nachtmusik, and overtures to Così fan tutte and Le nozze di Figaro were waxed by Walter four times.) The only other works he recorded thrice or more in the studio were Schubert’s Symphonies Nos. 8 and 9; Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Die Fledermaus and Der Zigeunerbaron overtures and Kaiserwaltz; and Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll (six times!), Siegfried’s Rhine Journey from Götterdämmerung, and the act I Prelude to Parsifal.

All of Walter’s Brahms recordings have appeared on CD, and are rightly regarded as classics; indeed, in the estimation of some collectors (myself included), Walter remains the nonpareil interpreter of Brahms, a composer with whose music he seemed to have a positively preternatural identification. His performances invariably achieve an ideal balance of drama and lyricism, penetrating to the heart of Brahms’s stoic but melancholic reserve. Unfortunately, although the Violin Concerto and the two piano concertos also were core items in Walter’s repertoire, Columbia turned to other conductors (most often Eugene Ormandy) for its recordings of those three works. In scattershot fashion, live performances previously have surfaced of Walter in all four symphonies, all four concertos, and the aforementioned overtures and choral works, but tracking those down and acquiring them is an onerous and formidable task.

With these three two-CD sets,

1/21/1951 – Tragic Overture, Violin Concerto [Zino Francescatti], Symphony No. 1

1/28/1951 – Haydn Variations, Symphony No. 3, Piano Concerto No. 1 [Clifford Curzon]

2/4/1951 – Hungarian Dance No. 17, Double Concerto [John Corigliano, Sr. and Leonard Rose], Symphony No. 2

2/11/1951 – Academic Festival Overture, Piano Concerto No. 2 [Myra Hess], Symphony No. 4

Portions of these programs have circulated underground among collectors of historic recordings such as myself, and a few items have appeared on CD. The Symphony No. 2 was issued in excellent sound by the now lamentably defunct Tahra label. The Piano Concerto No. 2 has also enjoyed fine releases on several labels, most notably Tahra and Music and Arts (the latter also was once briefly licensed by Pristine). The Symphony No. 4 and Double Concerto have surfaced in murky sound primarily on old pirate Italian labels (e.g., Nuova Era), though the former also appeared on a somewhat muffled Music and Arts issue. The Hungarian Dance No. 17 appeared only on an ultra-scarce Wing CD in Japan. The Symphonies Nos. 1 and 3 and the Piano Concerto No. 1 have been preserved only in private hands, the concerto in seriously defective versions afflicted with terrible radio hum and/or manifold drop-outs. The two overtures, the Haydn Variations, and the Violin Concerto from that cycle have not surfaced. (I once was given a privately made amateur LP pressing of the Violin Concerto; the quality of both the vinyl and the sound was sub-acoustic era level, and a section of one side was so badly scratched that it would not play through; but through it all one could hear a performance for the ages, very similar to the stellar live 1958 Francescatti/Mitropoulos/Vienna Philharmonic performance issued by Orfeo.)

For the missing items from this 1951 New York cycle,

How do these live performances compare with Walter’s commercial releases? One of the conductor’s signal traits was his ability to bring his concerts into the recording studio, as it were. He did not freeze up or turn stiff or overly self-conscious, and there is generally a very high degree of both consistency and inspiration between a given studio recording and a live performance by him of reasonably near vintage. Likewise, until his late, post-heart attack studio recordings from 1958 to 1961, there is remarkable similarity and continuity in Walter’s interpretations of a given work over time. In that sense, live performances do not add as much to our knowledge of Walter’s art as do, say, those of Wilhelm Furtwängler, whose individual performances could vary radically in character (and sometimes in quality as well). That is not to say that, however, Walter’s live accounts of works he set down in the studio are of comparatively little value. As always, there is often that subtle trade-off between the greater technical perfection of a studio recording and the intangible electricity and tension of a live performance, and that is the situation here. While I could live (and die) happily with either of Walter’s two studio cycles, I have a decided preference for the monaural versions of Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, and 4, esteeming all the other performances in both sets as being equally meritorious.

To my great surprise and pleasure, this 1947 Hollywood Bowl performance of The Song of Destiny

is a worthy rival for its 1941 studio counterpart. (In addition to the

1961 stereo version in German, there is a live 1952 performance from

Rome, sung in Italian, from the same concert as the Requiem in this

series.) Hugo Strelitzer (1896–1981) was originally an opera coach and

assistant conductor for various opera houses in Germany, who taught in

the Berlin Conservatory from 1926 to 1933. After being arrested and held

for six weeks in the notoriously brutal “Columbia House” SS prison (he

escaped death there due to the intervention of Furtwängler), he fled

Nazi Germany for the USA in 1936, where he joined the faculty of Los

Angeles City College, founded his choir that sang for Walter in this

performance, and established a very successful new career in opera that

lasted 25 years. The caliber of his choir’s singing is very close to

that of the Westminster Choir in the studio version from 1941 (both

groups have very good diction); likewise, in this particular work the

playing of the Hollywood Bowl Symphony does not compare badly with the

New York Philharmonic.

In all the other performances in this first set, the sonic trade-off is between the very clear but slightly dry sound of Columbia’s 30th Street studio in New York for Walter’s contemporaneous monaural recordings, and the less clear but more resonant acoustic of live concerts in Carnegie Hall. Individual listeners will have their preferences between hearing greater instrumental detail or sacrificing a degree of that for greater sonic warmth. The sound quality of the January 21 concert for the Symphony No. 1 is particularly fine, being almost of studio quality; that of the complete February 4 concert (the Hungarian Dance No. 17, Double Concerto, and Symphony No. 2) presented on CD 2 of this set is also quite good for its era, but has significantly more tape hiss in the high frequencies.

The two versions of the Hungarian Dance No. 17 and the Tragic Overture are virtually identical, though the live version of the former seems to me to have greater ripeness. (Somewhat oddly, the concert originally advertised that three Hungarian Dances, Nos. 1, 2, and 17, would be performed, but only one was actually played. On the unedited copy of the complete concert broadcast in my possession, one hears a prolonged awkward pause while the audience waits for the next dance to be played, and then belated applause in response to some signal from the stage. My suspicion is that the other two dances were dropped to create time for a fund-raising plea for the orchestra by Clare Boothe Luce as the intermission feature.) Likewise the two versions of the Symphony No. 2 are very close in character, though the live performance seems to me to have a bit more plasticity and to be slightly more relaxed in the finale (where it runs 20 seconds longer). Both accounts are splendid, and I could live happily with either one or the 1960 stereo version. (The other live performances that have surfaced on CD—the NBC Symphony in 1940, the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1944, the Berlin Philharmonic in 1950, and the Orchestre National de l’ORTF in 1955—are all sonically and interpretively inferior to these three.)

The greatest differences occur in the Symphony No. 1 and Double Concerto. The finale of the symphony is a full minute longer in the live performance (15 vs. 16 minutes), and I find the extra breadth beneficial; in the live performance, the famous horn call really is a ray of sunshine suddenly breaking through the clouds. More unexpectedly, concertmaster John Corigliano, Sr. is far more prominently miked in the live performance than in the later studio account, though not in an unduly unbalanced way, and thus shines to an extra degree in the second movement. Again, these two performances and the 1959 stereo version are all highly preferable to Walter’s other recordings (a 1937 studio recording on 78-rpm discs with the Vienna Philharmonic and a 1939 NBC Symphony broadcast). But, pressed to make a single choice, I might well elect this newly issued live rendition.

While Walter’s two studio recordings of the Double

Concerto—with Isaac Stern, Leonard

The second two-CD set brings a world premiere release of the Symphony No. 3—and what a glorious performance it is! The sound quality is exceptionally fine here, and Walter’s tautly dramatic but impetuous account, of Toscaninian fieriness while leavened as always with idyllic lyricism, supersedes even his 1953 New York studio recording that has previously been my benchmark. To my mind, the single most difficult part of the symphony to bring off is the hushed coda to the finale that follows all the fireworks; heretofore to my ear neither Walter nor any other conductor had made a fully satisfactory rendition of this epilog, but here it is molded to exquisite perfection. The Symphony No. 4, in sound much richer and less congested than on its Music and Arts predecessor (there are also previous, privately circulated, NYP performances in poorer sound from 1942 and 1945), likewise now assumes a premiere place for that work in Walter’s discography. My one prior point of dissatisfaction with Walter’s interpretations of Brahms has been in the finale to this work, where I have always found his pacing too slow in the final variations and failing to generate the sense of implacable doom conveyed so well by Furtwängler. Here, if still not quite plumbing the depths of tragedy reached by his rival (the two had a rather uneasy relationship), Walter here maintains much greater momentum in those closing pages and makes a complete success of them in his own right, and of course is masterly at every other point.

As previously mentioned, the two concertos

featured here have both been favored with excellent releases in the

past; but

The third volume returns to the Hollywood Bowl again for the performances of the Academic Festival Overture and the Haydn Variations.

The former is given a somewhat frenetic reading, and the ensemble gets

shaky at one point, with upbeats and downbeats between different

sections of the orchestra not properly in sync for a few measures; the

latter work goes considerably better, and both receive spirited

readings. While neither one can compete, sonically or interpretively,

with either Walter’s monaural or stereo studio accounts, they are at

present the only live performances we have of him in this repertoire,

and are to be welcomed for the additional insights they provide into his

artistry. The same is even more true of the Alto Rhapsody

presented here; dating back to 1941, it features a mediocre soloist in

Enid Szantho and poor recorded sound (though

By contrast, the Piano Concerto No. 1 with

Clifford Curzon, given its world premiere release here, is a find of the

first magnitude. Curzon’s 1962 studio recording of the work with George

Szell and the London Symphony has long been the benchmark

version for many a collector; his 1953 monaural account with Eduard van

Beinum and the Concertgebouw is also highly regarded. For his part,

Walter has one other surviving live performance of this work, with

Vladimir Horowitz and the Concertgebouw Orchestra dating from 1936. It’s

an absolutely stupendous rendition of jaw-dropping virtuosity,

heart-breakingly marred by the lack of one 78-rpm side in the middle of

the first movement (which Music and Arts has valiantly filled in with

the corresponding portion—in extremely poor sound, alas—of the 1935

Horowitz/Toscanini/NYP performance). Here, in an especially happy

marriage of talents, Walter draws out of Curzon a matching degree of

lyricism not found in those two studio accounts, without any lessening

of tensile strength. Granitic drama is still present in abundance, but

in many orchestral passages Walter opens the score to contrasting

passages of yearning tenderness; one can positively see green-forested

Rhineland valleys bathed in early morning sunlight. And, what

Finally, the series closes with something of an oddity—a 1952 performance of Ein deutsches Requiem

sung in Italian. While the 1954 concert broadcast apparently survives,

it has never surfaced and I’ve never heard it (the purported Archipel

release is actually the contemporaneous studio recording with applause

tacked on the end). That left

It is seldom that a historic release series as a whole merits the landmark status of this one, both for the featured artist and the composer. All three volumes are indispensible additions to the collections of any and everyone who either collects historic recordings or loves Brahms. All three volumes will jointly constitute the initial entry on my 2017 Want List. “Highest possible recommendation” is simply not good enough here; this is beyond all praise.

James A. Altena