This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

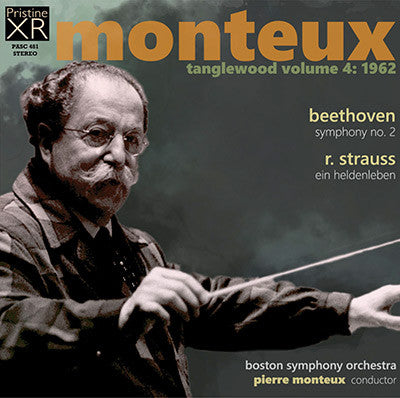

Monteux's stereo Tanglewood broadcasts part 4: Beethoven & Strauss, 1962

"Monteux

really does everything right in both works: despite the flexibility of

his tempi, the tension throughout the whole half hour of the symphony is

gripping" - MusicWeb International

The 1962

concerts started with two identical programmes, of which these

recordings were taken from the second concert. The programme began with

an orchestrated organ work by Bach, followed by the Beethoven, an

interval, and the Strauss presented here. The programme suggests that a

last minute change due to illness meant the Bach replaced vocal music

from Purcell and Weber - the Beethoven and Strauss were always planned

here.

Of these, the Beethoven is a lovely performance, but it is

perhaps Ein Heldenleben which stands out as particularly inspired and

righly brings the house down after some brilliant playing and

well-judged pacing. Naturally the Boston Symphony is excellent

throughout. Sound quality on these XR remasters of excellent if

originally slightly hard-sounding stereo source recordings is truly

superb - an ongoing improvement from the previous years' recordings can

be clearly heard and enjoyed.

Andrew Rose

- BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36

- R. STRAUSS Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40

Concert of 29 July, 1962

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Pierre Monteux, conductor

Recorded at the Koussevitzky Music Shed, Tanglewood

Reviews: Fanfare & Audiophile Audition

The level of musical execution has been exalted, lyrical, manic, and entirely resilient in all parts, and the BSO audience knows it

Pierre Monteux was 87 when he led this concert at Tanglewood in July of 1962. The year before, he made headlines by becoming the oldest-ever chief conductor of the London Symphony, on condition that he be given a 25-year contract. As in the many concerts that Leopold Stokowski, Adrian Boult, and Pablo Casals led in their 90s, it’s always a delight listening to a man who refuses to act his age.

From the glowing opening chord of Beethoven’s Second Symphony, it’s obvious that this is prime Monteux: unforced, relaxed, beautifully played, supremely musical. And although Monteux’s Second is a familiar commodity thanks to his commercial recordings with the San Francisco and London Symphonies—and a bracing live performance with the French National Orchestra available from Music and Arts (1182)—this Boston Symphony version is unmistakably in a class by itself. As the introduction gives way to the first movement proper—and how unerringly the conductor paces all the important transitions—it’s clear you’re listening to a vigorous young conductor who only happens to be in his ninth decade of life. The playing crackles with excitement, each perfectly placed accent the musical equivalent of a mot juste. Similarly, the Larghetto couldn’t be more warmly human, the scherzo more witty, the finale more full of character and bustling life.

While the basic contours of the Monteux Heldenleben are not that far removed from the conductor’s 1947 San Francisco recording, both the playing and sense of occasion are in an entirely different league. As always, the Boston Symphony plays with the reflexes and sensitivity of a fine chamber ensemble, but they also make some spectacular massed sounds, as in “The Hero’s Battlefield,” which erupts in a splendidly controlled chaos. Although a few things (inner voicing, mostly) get covered in the live recorded sound—the open-air Koussevitzky Music Shed has never been an acoustical match for Symphony Hall—the remastered sound is dazzlingly full and transparent for its period: a remarkably faithful approximation of what it’s like in a seat in the central section, some twenty or thirty rows back.

If it would be difficult to over-praise the orchestra’s playing, then there are still some minor drawbacks. Concertmaster Richard Burgin—also in his final season as the orchestra’s associate conductor—sounds uncharacteristically bleached-out and tentative, undoubtedly the result of the less-than-flattering microphone placement. All the other solo voices come off superbly, except for the typically thin and wobbly English horn. (That would be corrected two years later, when the BSO raided the Chicago Symphony for Laurence Thorstenberg, the great American English hornist of his time.) Ultimately, though, it’s the conductor who makes this Heldenleben the unique experience it is: one of the most flawlessly judged, thoroughly adult of all recorded Strauss performances, with nothing done for personal glory or cheap effect. In short, it’s an example of the kind of selfless yet intensely individual conducting that has all but vanished today.

Jim Svejda

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:4 (Mar/Apr 2017) of Fanfare Magazine.

Producer Andrew Rose extends his rewarding survey of the Pierre Monteux legacy at Tanglewood, here in 1962, a year in which the famed French maestro appeared six times before his old colleagues of the Boston Symphony. The music of this concert comes to us on 29 July 1962. The reading of the Beethoven Symphony No. 2 (1802) revels in its boundless mirth, despite the fact that at the time of its composition Beethoven felt the first real strains of his oncoming deafness. The first movement has Monteux’s urging his horns to exploit the ceaseless energy of its sudden injections of buoyant vitality. The strings whirl at dizzy pace, the tympani’s marking the cadences with gusto. Berlioz had claimed that the D Major Symphony smiles in every bar. The peroration that Monteux achieves at the coda becomes breathtaking, symmetrical in its ecstasies to the point that the audience barely contains its applause.

The enchanting Larghetto, a song that Berlioz envied, flows with lyrical exaltation. The ensuing ornaments and arioso flourishes develop a marvelous canvas, as virile as it is delicate. The color of the BSO’s lower strings, the violas and cellos, proves affecting at all points. The woodwind choirs impart the feeling that whatever martial elements invade the progress of the music, Beethoven still means to deliver an outdoor serenade. Beethoven’s first truly so-marked Scherzo moves with a pompous ease, breezy and witty. The Trio enjoys a pomp and humor – especially in the bassoons – that Haydn would savor. The da capo enjoys a mad dash straight to the Finale’s rollicking Allegro molto that convinces us that Beethoven has penned a second scherzo – here in supple meter – as his concluding movement. Once more, the BSO horns and strings achieve a buoyant enthusiasm that verges on menace but retains a jovial acceptance of life’s trials as well as triumphs.

The Richard Strauss Ein Heldenleben (1898) celebrates “the Heroic Life,” and its autobiographical conceits depict Strauss and his former-pupil wife, soprano Pauline de Ahna. Given Monteux’s long association with the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam and its eminent conductor Willem Mengelberg – to whom the score is dedicated – Monteux’s sympathy with the music seems entirely natural. Rather intricately co-ordinated into six flowing sections, the huge symphonic poem traces the composer’s quest for greatness and the various oppositions and supports he meets along the way. The solo violin (possibly Joseph Silverstein) intones the many moods – splendid and petty – of Pauline’s support in times of adversity, mostly in the form of carping critics and their bleats, which sound unsurprisingly like the sheep in Don Quixote.

There are various miracles of orchestration in the course of the Strauss self-promoting legend, such as weaving an amazing tapestry from his own scores, including the failed 1893 opera Guntram, Macbeth, Death and Transfiguration, the song “Dreaming at Twilight,” Don Quixote, and the jubilant Don Juan, for his “The Hero’s Works of Peace” movement. Prior to this self-celebration, Strauss had engaged in epic battle, with startling effects from the BSO battery and brass at Monteux’s ready disposal. At last, the Hero withdraws – presumably to Switzerland, if the English horn provides any clue – finding a consolation, a “consummation,” in no less than in archetypal, heroic strains in Beethoven’s Eroica. The level of musical execution has been exalted, lyrical, manic, and entirely resilient in all parts, and the BSO audience knows it.

—Gary Lemco

Audiophile Audition