This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

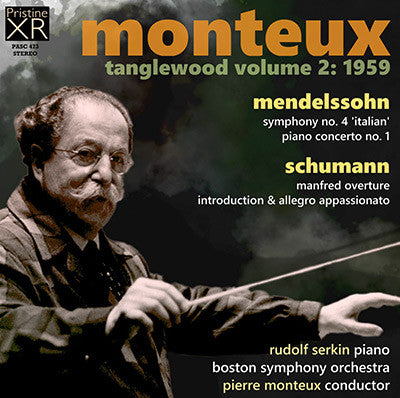

Monteux's stereo Tanglewood broadcasts part 2: 1959

"The performance here proffers a musical fireball by two acolytes of the Romantic ethos" - Audiophile Audition

For this second volume of live broadcast recordings by Monteux and

the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood we revisit a concert held on

1st August, 1959. The concert is presented as performed, minus the

lengthy introductions from the radio announcer and, alas for reasons of

time, the final Wagner Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan. I hope that

this will appear, along with other recordings from this short series, on

a final disc compiled from the different years we are covering.

Once

again the sound is big and wide, though more controlled than in 1958,

and I've resisted the temptation to narrow it as was necessary in the

previous volume. Whilst there is perhaps the hint of a gap in the middle

during the orchestral pieces, this is well filled when Serkin takes to

the piano. As before, close miking resulted in a slightly over-dry sound

quality to the original broadcasts, something I've been able to

alleviate in a manner sensitive to the material. Sound quality in both

broadcasts was excellent, and has been very well preserved, with one

minor tape dropout easily cured. XR remastering has further enhanced the

sound, and careful digital noise reduction has lowered tape hiss

levels, more prominent in the second half of the programme, without

impacting on the clarity of the recording.

Andrew Rose

-

MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 90, 'Italian'

- MENDELSSOHN Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25

- SCHUMANN Manfred, Op. 115 - Overture

- SCHUMANN Introduction and Allegro appassionato, Op. 92

Concert of 1 August, 1959

Rudolf Serkin, piano

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Pierre Monteux, conductor

Recorded at the Koussevitzky Music Shed, Tanglewood

Reviews: MusicWeb International & Audiophile Audition

Power and sweep conveyed through a stern, propulsive sinewy reading...

This isn’t the first time that this Tanglewood concert has appeared.

Back in 2012 it turned up in a large West Hill Radio Archives box

devoted to Monteux’s Boston performances that was favourably reviewed

here by John Quinn (review),

an excerpted paragraph of whose text forms part of the documentation

for this Pristine Audio release. What is missing from this latest

transfer, for reasons of space, is the Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan, though Pristine hopes that it will appear in a later volume in this mini-series. It’s available in that WHRA box.

Monteux was an erratic Mendelssohnian. The Fourth Symphony saw him at

his most quixotic, and an earlier preserved example of his way with the

Fourth Symphony saw me spitting feathers in a previous review of Sunday

Evenings with Pierre Monteux (review)

on Music and Arts. This 1959 example has a somewhat more temperate

first movement but it is still bass-heavy and too fast, giving it a

rather galumphing quality, that never settles. Whether Monteux was

trying to inflate symphonic Mendelssohn to make a point or was

subconsciously hustling through to keep up with the likes of Cantelli,

is a debate that will lead nowhere. He does at least take the first

movement repeat. Things stabilise thereafter – the third movement is

definitely ‘con moto’ - but the sound is cool and a bit dry and doesn’t

flatter in its lack of resonance. The Saltarello is, once again,

big-boned.

For the First Piano Concerto he was joined by Rudolf

Serkin, who improves as the work develops. Dropped notes in live

concerts don’t especially concern me, though Serkin drops his fair share

and sounds a little uncomfortable during the first movement, and

neither man is given to rococo elements in this work. By the finale,

however, things are motoring purposefully.

The remainder of the

concert is devoted to Schumann. Serkin is on good form in the

Introduction and Allegro Appassionato and in Manfred we hear Monteux

approaching something like his best in this disc – power and sweep

conveyed through a stern, propulsive sinewy reading.

That said,

there are erratic and interpretatively individualistic elements aplenty

in this disc. If you’ve not encountered it before it may be useful in

drawing out the nature of Monteux’s affiliations – a stronger conductor

in Schumann than Mendelssohn on this showing.

Jonathan Woolf

MusicWeb International

The concert of 1 August 1959 for the summer music festival of the Boston Symphony features two veteran musicians, Pierre Monteux (1875-1964) and pianist Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991). Collectors are likely aware that Serkin recorded the two concertante pieces for CBS with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra under slightly less manic conditions. Still, if one can forgive Serkin’s finger slips – mostly in the Concerto’s first movement – the performance here proffers a musical fireball by two acolytes of the Romantic ethos.

Monteux opens with a work he did not record for RCA commercially, the “Italian” Symphony of Mendelssohn. Monteux takes the oft-neglected repeat in the first movement, and then proceeds to compensate for the added minute by injecting a heated velocity into the remainder of the movement. The audience applauds the players for their sheer bravura. The proceeding movements enjoy both a fleet pace and sensitive articulation, light-footed and eminently enthusiastic. Always a stickler for interior-voice clarity, Monteux fashions an Italian romp that has energy and singing virtuosity.

Schumann’s gloomy Overture to the Byron poem “Manfred” has had its ponderously “profound” moments, but this is not one of them. More interested in propulsive drama, Monteux maintains a distinctly tragic quality in the music while driving it inexorably forward. In this respect, Monteux’s reading reminds me of that by Beecham. The upward scales in the late pages enjoy a potent momentum whose burnished string sound testifies to “the aristocrat of orchestras.” The BSO brass prove no less fervent and deserve high praise for their epic sonority, insofar as Nature teaches Manfred “the language of another world.”

Schumann intended the 1849 Introduction and Allegro appassionato as a display piece for wife Clara, after the initial success of the Concerto of 1845. Its opening filigree enjoys a pastoral range of harmony, and Serkin appears in his most poetic form. The rather imperious march that constitutes the second half of this rousing sixteen-minute work suggests another of Schumann’s calls to arms against the cultural philistines. The martial elements of the second section have their foil in dreamy, nostalgic phrases in waltz-character. Some liquid French horn work and opulent upper brass announce the composer’s aesthetic and moral victory. The clapping has burst forth long before Serkin’s final notes.

—Gary Lemco

Audiophile Audition