This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

The late genius of Pablo Casals - his first and his final post-war concerto recordings

Live festival recordings - including the much sought-after stereo Dvorák from Puerto Rico in 1960

At the end of the Second World War, Pablo Casals hoped that the Allied forces which had just ousted Hitler would now turn their attention to removing the dictator Franco from Spain. When they showed no inclination to do so, he broke off a London recording session of the Haydn D Major Cello Concerto in October, 1945 and withdrew to his French home in Prades near the Spanish border, vowing not to perform publicly again until democracy was restored to his homeland.

He was drawn out of his self-imposed silence by Budapest Quartet violinist Alexander Schneider, who first approached him for coaching help with the Bach violin suites, and who later suggested holding a festival in Prades to mark the 200th anniversary of Bach’s death in 1950. American Columbia was brought in to make recordings, a series which continued as the festival expanded its purview beyond Bach and moved to larger quarters in nearby Perpignan in 1951, returning to Prades the following year.

While Casals had conducted and played in chamber music performances, the Schumann from the 1953 festival was his first concerto recording as a soloist since the aborted Haydn set. Interestingly, master accompanist Eugene Ormandy was not credited on the original LP, nor on its first reissue in the budget-priced Odyssey series, probably for contractual reasons. In 1957, a new series of Casals festivals was begun in Puerto Rico, where the cellist had recently married and made his home. It was there that his final concerto recording was made.

The Dvořák has an interesting history. Recorded by Everest during the 1960 Puerto Rico festival, it remained unapproved when the label changed hands shortly thereafter. The new owners found the tape in a box and issued it, believing they owned the rights. Casals promptly sued to have the release withdrawn, claiming it damaged his reputation. It has never subsequently been reissued in any authorized edition from the Everest masters, although a couple European CD releases, apparently transferred from monaural sources, have appeared. The original suppressed LP is now a highly sought-after collector’s item. I was fortunate to have two stereo pressings in good condition to work from for the present transfer. (The first note, incidentally, is clipped on the original recording.)

While Casals is admittedly not in top form, his performance brings to mind Dr. Johnson’s famous Eighteenth Century witticism likening a woman preaching to a dog walking on its hind legs (“It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”) Considering that he was in his 84th year at the time, it is a remarkable achievement; and Schneider’s heartfelt, sympathetic accompaniment matches his soloist like the veteran chamber player he was. It’s an autumnal reading quite different from Casals’s brisker 1937 recording with Szell (Pristine PASC 246), and one which despite its flaws deserves to be heard.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op. 129

Eugene Ormandy

Prades Festival Orchestra

Recorded 28 May 1953 in L’Église St-Pierre, Prades

First issued on Columbia ML-4926 -

DVOŘÁK Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 (STEREO recording)

Alexander Schneider

Festival Casals Orchestra of Puerto Rico

Live recording, Spring, 1960, in the Theatre of the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan

First issued on Everest SDBR 3083

Pablo Casals cello

Fanfare Review

Anyone who has looked attentively at the headnote will already have observed that this is not the classic account of Dvořák’s B-Minor Concerto that Casals recorded with George Szell and the Czech Philharmonic in 1937. Instead, this is a pirate recording that has (or at least did have) a legendary status among collectors of historic recordings, albeit for an idiosyncratic reason. The live performance from Puerto Rico was originally taped for intended commercial release by the Everest label. However, the label changed hands while the tape was still waiting approval by Casals for release. The tape was subsequently found in a box; the new owners assumed that permission to release it had already been obtained and issued it on LP. Casals promptly sued, charging damage to his reputation, and Everest recalled the LPs. The few copies that had been sold promptly became collectors’ items, commanding hundreds or even thousands of dollars whenever one turned up on a used record dealer’s list. Eventually, a CD transfer appeared on the AS disc label from Italy in the late 1980s, which was how I finally made its acquaintance (spending a mere six dollars for a used copy and congratulating myself on obtaining the bargain of the century). More recently, a Memories CD appeared with the identical coupling as on this Pristine Audio disc, and I duly replaced the AS Disc with that copy.

For anyone considering acquisition of this disc, then, the questions that arise are:

1) How does this performance of the Dvořák Concerto compare with the 1937 studio version?

2) How does the sound quality of this issue compare with that of previous versions?

The answer to the first question is rather complex. Casals was 84 years old (or young) at the time of this performance, and it is universally conceded that his technique was no longer what it once was in his prime. There are some rough bow strokes and attacks, and in particular quite a number of lapses in intonation, some minor but a few major. When compared to the immaculate precision of his 1937 studio account, one can readily see why Casals might sue to block issuance of this release on ground of damage to his reputation. And yet....And yet....From the moment I first heard this performance it became, despite these evident flaws, not only my preferred version over the 1937 account, but one of my favorite recordings of this concerto—which, given that the work belongs to my short list of all-time favorites, is saying quite a lot. For all its fame, the 1937 account has never really won my heart rather than my respect, for reasons detailed by Bernard Jacobson in his review of an EMI rerelease back in 29:2. (For more conventionally laudatory reviews, see those by John Bauman in 13:1 and Jerry Dubins in 34:6. By contrast, Szell’s stereo account with Pierre Fournier is one of my preferred versions.) But in this live performance, Casals seems to be pouring out his life’s blood; there is not a single other recording by him I have heard, live or studio, that has such gripping ardor. When faced with artistry of this intensity from a deservedly legendary figure, cavils about technical lapses become for me irrelevant niggling quibbles.

To this one must add the absolutely masterful conducting of Alexander Schneider, second violinist of the celebrated Budapest Quartet from 1932 to 1943 and again from 1955 to 1967, who was instrumental in persuading Casals to renounce his withdrawal from public performance in protest against the Franco regime in Spain return to concertizing at Perpignan, Marlboro, and Prades. One wonders if the multi-faceted Schneider missed his true musical calling (he also turned down a offer to conduct at the Metropolitan Opera), so completely does he command every expressive nuance of this score. I do not know if the orchestra was an ad hoc ensemble assembled for the festival or a local orchestra playing under an assumed name, but it too plays its collective heart out with a dedication that could put many far starrier ensembles to shame. Admittedly, all of this is a highly subjective response; I wouldn’t criticize anyone who found the faults in Casals’s playing here to be reason enough to prefer the 1937 studio version instead. But I would urge you to give this a hearing, and see if it doesn’t win your affections as it did mine.

The second question is much more easily addressed. In the Schumann, the sound quality of the Memories CD and this one is very close; I slightly prefer the Memories issue, but only by a hair’s breadth. The Dvořák Concerto, however, is another matter entirely; with access to two genuine stereo Everest LP releases for making its transfer, Mark Obert-Thorn has produced a vastly superior version with sound quality that renders every previous issue obsolete. If you have one of those previous versions, replace it with this one immediately and prepare to be amazed at the difference.

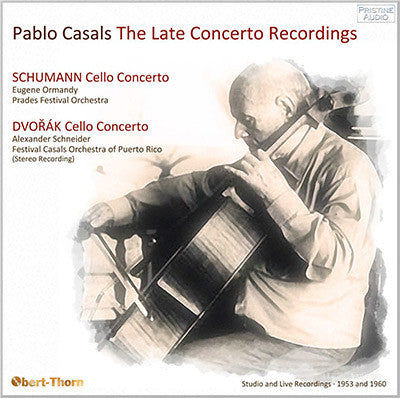

By contrast, the Schumann is a much better-known recording with a far more ordinary history, having first appeared on a Columbia LP, albeit with the conductor curiously uncredited, presumably for contractual reasons. (Contrary to a note on the front cover of this release, it too is a live and not a studio account, as the loud opening groan from Casals as he plays his first phrase reveals.) The piece itself is highly problematic, of course, and I don’t ever recall seeing a review that ranks this as one of the premiere versions that overcomes the score’s deficiencies. That said, it is still a Casals performance—and this, the two of the Dvořák, and the Elgar, are his only recordings of major concertos—played with his unique interpretive authority, and Ormandy is certainly no podium slouch. The monaural sound quality is clear and solid, albeit with some underlying tape hiss. The cover art of Casals playing his cello is quite attractive, a great advance upon Pristine’s previous graphics. While for the reasons stated above this is too subjective a choice to put on my 2014 Want List, I’ll still go out on a limb and give this my strongest recommendation; I simply couldn’t imagine being without it.

James A. Altena

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:6 (July/Aug 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.