This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

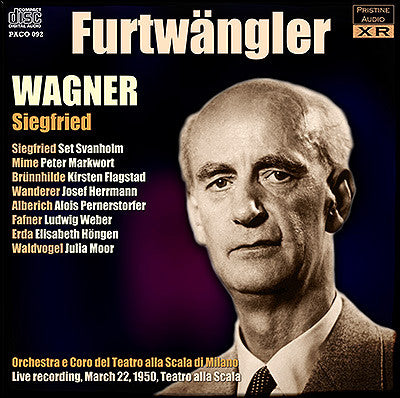

Furtwängler's 1950 Ring Cycle Part 3: Siegfried

"Towering above all are the two complete cycles left in recorded form by Furtwängler" - Fanfare

After all the various issues of Furtwängler's 1950 La Scala Ring cycle over the years - elsewhere in his 1996 review quoted here Henry Fogel remarks: "when it was on the Everest and Murray Hill labels, it was unspeakably bad—including being at the wrong pitch" - the general opinion was that this was the better performance in much the worse sonic condition of the two recordings which exist of Furtwängler conducting the Ring.

Thus far the reaction to our XR-remastered issues of this Ring Cycle have been exceptionally positive - particularly from those who've followed those various releases through since those first almost-unlistenable LP issues.

When marking up the tracks for this release I used our previous issue of Furtängler's 1953 RAI Ring as a guide - and was repeatedly struck by just how much the better of the two the older recording sounded. By getting the pitching spot on (a clear 50Hz hum indicates the performance took place at A=446Hz) and trimming applause to a minimum, I've been able to fit each act onto a single disc, with the only cut being Furtwängler's own in Act 3. As in previous operas in the cycle, sound quality slips occasionally for a few seconds at a time - that aside it really does sound quite amazing.

Andrew Rose

WAGNER - Siegfried WWV 86C

Siegfried Set Svanholm

Mime Peter Markwort

Brünnhilde Kirsten Flagstad

Wanderer Josef Herrmann

Alberich Alois Pernerstorfer

Fafner Ludwig Weber

Erda Elisabeth Höngen

Waldvogel Julia Moor

Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala di Milano

conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler

Live recording, March 22, 1950, Teatro alla Scala

Fanfare Review

As an owner of the Murray Hill LPs that the Furtwängler Ring appeared on, let me say that I’m astonished at how good these CDs sound—this is some resuscitation!

As an owner of the Murray Hill LPs that the Furtwängler Ring appeared on, let me say that I’m astonished at how good these CDs sound—this is some resuscitation! I still entertain my reservations about the casts; much of my pleasure in these performances comes from the pit and the podium, especially the latter. Back in 1950, when these performances were (fortunately) preserved, who would have guessed at the number of complete recordings of Der Ring des Nibelungen would have been issued by now, so many of them good ones? Conductors such as Karajan, Keilberth, Kempe, Knappertsbusch, and Krauss have had their say; in fact, one doesn’t have to have a surname beginning with the letter K to conduct the Ring operas well—witness the various operas that were recorded by Dohnányi (unfortunately, only Das Rheingold and Die Walküre), Haitink, Levine, Sawallisch, Solti, Weigle, and Young. Nevertheless, I think the maestro who would conduct my all-time Ring is the man who led these Milan performances and then surpassed them in Rome three years later. I wonder how Pristine’s transfer of the RAI Ring sounds—the RAI recording was kinder to the singers, whereas the sonic balance in these La Scala performances definitely favors the orchestra. This doesn’t trouble me because, for me, that is the principal attraction of these performances. Some listeners may even like the fact that the singers sound like they are up there on a stage and you’re hearing them from the auditorium. The imbalance does take much of the authority from some of the cast but not from its oldest member, Kirsten Flagstad, the only one other than Ludwig Weber to have been born in the previous century—no one is going to drown her out and, while she may choose to skip a few high notes, her voice sounds healthy and powerful and she even seems attentive to the text.

In Siegfried, she’s joined by a longtime colleague, Set Svanholm, surely the greatest of the post-Melchior Siegfrieds (some people even preferred him). For two acts, he sings with his expected authority, including a terrific forging scene. In act III, Furtwängler omits a huge chunk of the Siegfried/Wanderer confrontation. This relatively brief scene is not normally a candidate for cuts and, given the events of the following scene, I think I know why, for, as scene 3 progresses, it becomes apparent that Svanholm is a singer in distress, grabbing for top notes and occasionally attacking just under them. He manages to get through it without any major mishaps but you can sense his fatigue. Was he indisposed or merely tired? Fortunately, there are two studio recordings of the scene which demonstrate what he could actually do with the music, one with Flagstad, the other with Eileen Farrell (a dream Brünnhilde). Peter Markwort is a suitably cringing, whining Mime—central Europe seems to produce a lot of good Mimes; I wish they could produce a few more good Siegfrieds. As his equally evil brother, Alois Pernerstorfer fills the role adequately, though I’ve heard more menacing ones. Josef Herrmann strikes me as a relatively weak Wanderer, lacking the authority of some later Wanderers. Next to Flagstad, the strongest voices belong to Ludwig Weber (Fafner) and Elisabeth Höngen (Erda), neither of whom is on stage for very long. What makes the performance special is the intensity and rhythmic suppleness of Furtwängler—the subtle way he underlines passages, the way the tempo expands and contracts, the intensity of the playing. This is a good orchestra, but he wasn’t necessarily the easiest conductor in the world to follow. They probably had had little experience with him, but they certainly rise to the occasion with minimal mishaps.

The same thing goes for the playing and conducting in Götterdämmerung. Flagstad pours it on—the quality of her voice and her stamina are remarkable. The Siegfried, Max Lorenz, gets credit for stamina, too; even in “Siegfried’s Death,” he can still get the high notes out, but what used to be a voice with some metal in it had apparently become merely generic by 1950. Having sung the role many times, he knows what he’s doing and gets the message across, but there’s little pleasure to be had from his voice, per se. Weber is a relatively subtle Hagen but has the power when he chooses to unleash it; personally, I prefer an even darker voice in the role, like those of, say, Ludwig Hoffmann or Gottlob Frick. Josef Hermann seems to find Gunther to be a more congenial role than the Wanderer, though he hardly compares with such later ones as Stewart and Uhde. He just can’t “do” much with his voice. I will yield to the temptation to refer to “the thankless role of Gutrune” (which is almost a cliché) and sympathize with Hilde Konetzni, who sings it so well. As Waltraute, Elisabeth Höngen holds her own with Flagstad in their big scene—what more praise can I give? The various Norns (Konetzni doubles as number three) and Rheinmaidens are fine. I might mention that Wieland Wagner thought the Norns scene was superfluous and actually considered cutting it when the opera was presented at Bayreuth. Furtwängler began a studio Ring with the Vienna Philharmonic but, alas, only managed to finish Die Walküre before his death. That would have been a Ring to reckon with—some of it might have even ended up being recorded stereophonically and competed with Karajan and Solti’s later ones. In any case, we can consider ourselves fortunate to have two very listenable Furtwängler Rings along with so many other good ones.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:2 (Nov/Dec 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.