This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

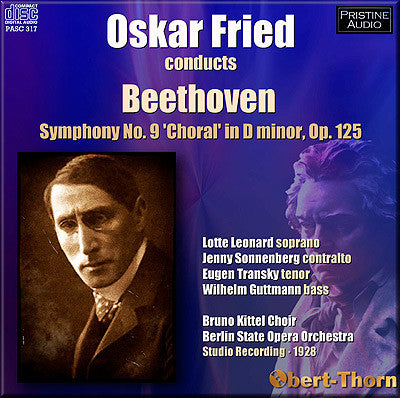

One of the first truly great recordings of Beethoven's Ninth

"Highly recommended as the best-sounding edition yet of an important recording in the Ninth’s early discography" - Fanfare

The source for the present transfer was a set of French Polydor pressings. The exact date of recording is not known; the “Mechan. Copt.” date given on the discs is 1928, although some discographic sources claim it was made the previous year. Some of the loudest choral passages overloaded the early microphones, causing a couple moments of sputtering which are inherent in the original recording.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

Lotte Leonard soprano

Jenny Sonnenberg contralto

Eugen Transky tenor

Wilhelm Guttmann bass

Bruno Kittel Choir · Bruno Kittel

Berlin State Opera Orchestra

Recorded in 1928 in Berlin

First issued on Grammophon/Polydor 66657 through 66663

1st movement matrices: 633 bm, 634 bm and 635 bm

2nd movement matrices: 588 ¾ bm and 636 bm

3rd movement matrices: 637 bm, 638 bm and 639 ½ bm

4th movement matrices: 586 ½ bm, 587 bm, 566 ½ bm, 564 ½ bm, 565 ½ bm and 567 ½ bm

Oskar Fried conductor

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Oskar Fried

Total duration: 62:05

Fanfare Review

Mark Obert-Thorn’s bright, open new transfer comprehensively outclasses the curiously dull, featureless one by David Lennick on Naxos

Oskar Fried’s early electrical Ninth (1928) comes as a welcome follow-up to Pristine’s recent release of his acoustic “Eroica.” The original recording was not one of the better ones of its day, poorly balanced with the woodwinds too distant. But Mark Obert-Thorn’s bright, open new transfer comprehensively outclasses the curiously dull, featureless one by David Lennick on Naxos.

Freid’s conception of the Ninth is lean, sharp-edged, and modernist, in the manner of Coates, Weingartner, and Toscanini—although from one perspective expressively more neutral, less highly dramatized than any of them, Fried’s ascetic rigor, at times evoking an almost Stravinskian angularity, is highly compelling on its own terms (interestingly, his style is far less expressively molded here than in his “Eroica” of a few years earlier). The first movement is very successful in its taut, punchy, incisive way, despite some patches of approximate ensemble. Edgy sextuplets set the scene and are much emphasized at their periodic returns later in the movement, with the effect of a subterranean stream bubbling to the surface. Phrases are driven forward with Fried’s trademark quickening thrust. I am less enthusiastic about the Scherzo, where the rhythmic drive becomes unsubtle, with overdone attacks on the fugal entries. It is also surprisingly inconsistent in tempo, with the da capo after the Trio taken very noticeably faster than first time through. Like Coates and Toscanini, Fried takes the Adagio up to tempo (or closer to it than most pre-period-performance conductors, at 14:05), though again his style is cooler and more detached, less singing, than either. But he is audibly galvanized in the finale, building and integrating the movement’s disparate elements most impressively. The solo quartet displays good teamwork, singing with incisive clarity, and the choral work really blazes, with an exciting sense of spontaneity.

This is highly recommended as the best-sounding edition yet of an important recording in the Ninth’s early discography, and a mandatory upgrade for those possessing the old Naxos disc.

Boyd Pomeroy

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:1 (Sept/Oct 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.