This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

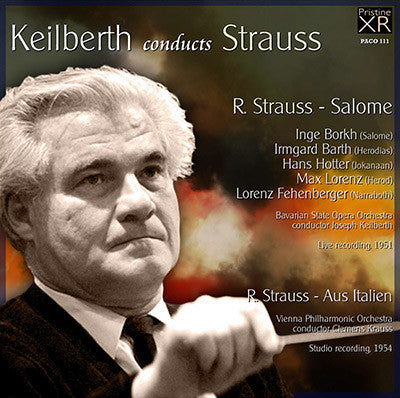

Keilberth and Krauss conduct a Richard Strauss double bill: Salome & Aus Italien

"Strauss

wanted Mendelssohn-like textures in his Salome. These Keilberth, one of

the last conductors to work with the composer, provides..." -

Gramophone

"I don’t know of any record that sounds better than this highly recommended one of Aus Italien" - The Gramophone

As live staged opera recordings of the era go, the 1951 Keilberth Salome was remarkably successful., giving me plenty to work from. This XR remastering has dealt with the rather constricted sound of the original, bringng out depth, a sense of space, and a sparkling top end that makes a huge difference to the dramatic impact of the performance. This had the unexpected bonus of improving the perceived balance between singers and orchestra to a significant degree, all of which is of great benefit to the overall impression of drama and what Gramophone's reviewer called a "vital sense of occasion".

I've coupled it with Krauss's 1954 Aus Italien at least partly because the works fit well onto two discs - there was no suitable Keilberth Strauss recording to fulfill this role. The Decca studio recording was indeed excellent for its day, but the tone was a little thin, especially at the bottom end. Again, though, I had a good start, and the full, beautiful tone of the Vienna Philharmonic can now be heard to great effect in one of Clemens Krauss's final recording sessions.

Andrew Rose

Inge Borkh (Salome)

Hans Hotter (Jokanaan)

Max Lorenz (Herodes)

Irmgard Barth (Herodias)

Lorenz Fehenberger (Narraboth)

Katja Sabo (Page)

Karl Ostertag, Peter Kaussen, Georg Binder, Walther Carnuth, Rudolf Wünzer (Fünf Juden)

Max Proebstl (Erste Nazarener)

Albrecht Peter (Zweite Nazarener)

Adolf Keil (Soldat)

Fritz Friedrich (Soldat),

Karl Hoppe (Cappadozier)

Bavarian State Opera Orchestra

Joseph Keilberth, conductor

Live stage performance, Munich Festival Hall, 21 July 1951

Transfer from Melodram MEL-S 106 (2)

R. STRAUSS Aus Italien, Op. 16

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Clemens Krauss, conductor

Recorded December 1953, Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Cyril Windebank

Issued as Decca LXT.2917

Fanfare Reviews

Delightful through and through, bathed in Italian sunshine filtered through Strauss

The premiere of Strauss’s opera took place in Dresden in December 1905. By the time five months had passed the opera had generated enough controversy that among the audience which attended the first Graz performance were Mahler, Puccini, and Schoenberg. Strauss may or may not have been being facetious when he said the opera contained no difficulties, describing it as “a scherzo with a fatal conclusion” and claiming that “it should be played as if it were by Mendelssohn.” I suspect that the anecdote that has him telling the orchestra to play louder “because I can still hear the singers” is apocryphal and much of Salome’s orchestration, despite the huge orchestral forces, is quite delicate and refined. He originally wanted the title role performed by a dramatic soprano despite the fact that few of them could convincingly pass as teenagers, much less actually perform the Dance of the Seven Veils. His choice as the original Herod was Carl Burrian (Karel Burian), a Heldentenor who sang nearly all the big Wagnerian tenor roles at the Met. Eventually, Strauss decided that lighter-voiced sopranos could sing the role after all, and among the eventual Salomes were Maria Cebotari, Lisa Della Casa, and Anna Silja. He even composed a thinner orchestration for use in smaller theaters, and recordings have made it possible for “character tenors” to play Herod, but the live broadcasts I’ve heard use Heldentenors: Set Svanholm (Reiner), Jon Vickers (Kempe), and Max Lorenz (Keilberth).

As you can see above, Keilberth’s dates from July 1951. Yes, it is monaural, but surprisingly vivid for an old radio broadcast. Joseph Keilberth, of whom I have never been a big admirer, holds his own with such recorded colleagues as Karajan, Kempe, Krauss, Sinopoli, and Solti, helped to a considerable extent by the fact that Salome is a piece of musical machinery that is difficult to ruin—once set in motion by a competent conductor and given a good enough cast, it’s going to work. Leading Keilberth’s cast is Inge Borkh, a celebrated Salome and Elektra who certainly puts across, at least, the aural picture of Salome as an impulsive, obsessive teenager. Hans Hotter’s Lieder smarts avail him little in so declamatory a role as Jokanaan—he’s good but really no better than Hans Braun (Krauss), Bryn Terfel (Sinopoli), Thomas Stewart (Kempe), José van Dam (Karajan) or Eberhard Wächter (Solti). The veteran Heldentenor Max Lorenz may not have been much of a Siegfried by 1951, but he could certainly handle Herod as well as anyone else I’ve heard perform it. Kempe’s live performance from the Orange (France) Festival has the cachet of Jon Vickers in a role he seldom (if ever again) undertook, but the director had him spending a lot of time toward the rear of the stage so this in-house recording minimizes his impact on the performance. Leonie Rysanek is a disappointing Salome who seems more concerned about being drowned out than creating a character. She’s the Herodias on Sinopoli’s recording, which stars Cheryl Studer, who takes full advantage of the fact that she doesn’t have to project her voice into a large theater. Bryn Terfel’s cistern seems a bit far away but you can always hear him. Horst Hiestermann is a more-than-adequate Herod. I used to think that Herbert von Karajan and Salome was a perfect match of conductor and opera and his recording did not disappoint me, nor did Hildegard Behrens’s performance of the title role. The rest of the cast is fine, too. Solti has the benefit of Birgit Nilsson’s terrific Salome, both dramatically as well as vocally. Gerhard Stolze, who might have been unsatisfactory in person, is able to create a nice, slimy Herod on the recording and Eberhard Wächter’s bang-it-out style works for Jokanaan. If you don’t mind a single channel, Clemens Krauss gave us a fine recording 60 years ago that still holds up well. Christel Goltz, Hans Braun, and Julius Patzak head the strong cast of Viennese veterans. I have hardly mentioned Herodias and Narraboth because these characters, while they contribute to the action, are not exactly make-or-break roles. Given the excellent two-channel recordings by Karajan, Sinopoli, and Solti, I can see little justification for recommending Keilberth’s 1951 broadcast, despite its obvious virtues. If it matters, Clemens Krauss’s 1954 studio recording of Aus Italien serves as a bonus filler, but in Pristine’s transfer the strings seem a bit too bright and disembodied from the orchestra. If I must listen to this overlong, early Strauss tone poem in a mono recording, I prefer Decca’s CD transfer of the Krauss (they were presumably able to work from the master tape). The most interesting thing about Aus Italien for me is that Strauss, under the illusion that it was a folk song, made several strong allusions to Luigi Denza’s Funiculi, funicula in the final movement only to discover, to his embarrassment, that it was under copyright.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:5 (May/June 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

This performance has been available before, but here appears under the Pristine label in a remastering by Andrew Rose. Previous commentators are right to identify Hans Hotter as the prime reason for acquiring the set. He sang the role with Strauss himself conducting (and not just once), so there is a sense of authenticity from that regard. And Hotter’s Jokanaan is indeed remarkable, his velvety voice still capable of carrying huge distances (even, ostensibly, from the bottom of wells). When he is first in focus (that is, at ground level) it is less imposing, more truly frightening, a prophet who surely should be in the Old Testament with its tales of utter violence. From this perspective, the outlay on the issue is fully vindicated. He is magnificent, a vocal Empire State Building. The top end of his voice never thins, maintaining the richness of tone, something vital in this role.

The sound on Pristine’s offering seems very open, and there is plenty of orchestra detail. It also sheds more light on Inge Borkh’s rather harsh sound and sometimes unpleasant vibrato. The surely deliberate petulance of the earlier parts of the opera opens out later, allowing the torment and, indeed, vortex of emotions to shine through. Max Lorenz starts off with plenty of vocal strength for Herod (“Salome, komm, trink Wein mit mir”), and manages to project the frustrations of obsession well, if not absolutely grippingly. He does seem to tire later, though; neither is his Herodias, Irmgard Barth, in top form.

However, Keilberth’s way with the orchestra is mightily impressive. There is amazing detail to the louder passages lost in many other recordings, a fact particularly impressive given the provenance of the issue. He seems to have an instinctive grasp of the light and shade (there is light) of the score, and his realization of Strauss’s harmonic points have just the right amount of give for them to register fully without degenerating into point-making. The foregrounded percussion at the outset of Salome’s Dance is somewhat surprising; the way Keilberth slides into the dance itself via the slithery bass figures more than compensates, as does the way he paces it inexorably towards its climax as if it were a Ravel Boléro viewed through a hallucinogenic kaleidoscope. Keilberth shapes the final portion of the opera like a master, increasing the horror of the unfolding story (listen to the vivid bass, perfectly retained here in this issue, around “Ach ich habe deinen Mund geküssst,” towards the end of the opera: The hollowness of that bass, the sparseness of the texture and the desolate wind figurations tell the whole story. The Modernist shrieks of the final pages are viscerally rendered.

The performance of Aus Italien was issued on Decca LXT2917, produced by Victor Olof. Recorded in December 1953 in the Grosser Musikverein, this is a much undervalued score (I for one have yet to hear it live), yet it holds much of value. Krauss is here fortunate to have the golden sound of the Vienna Philharmonic at his disposal: Listen to how the opening of the first movement, “Auf der Campagna,” glows with an inner light. The long violin lines are dripping with affection above a lush carpet of an accompaniment. There is no sense of apology for the youth of the composer here (it was written in 1887). One can discern the great orchestrator (try the opening of the third movement, “Am Strande con Sorrent”), and many Strauss fingerprints are there (the rhythmic figures of the second movement, “In Roms Ruinen,” for example, given with such accuracy by the Vienna players). The score is, at many points, simply magical and has lain in the shadow of the more famous tone poems for far too long. Keilberth is a miraculous guide, allowing the lines to breathe naturally. The explosion of the finale (“Neapolitanisches Volksleben”) uses a tune by Denza (you’ll know it, for sure) which apparently Strauss mistook for a Neapolitan folk tune. The finale is in fact delightful through and through, bathed in Italian sunshine filtered through Strauss. Interpreted by the VPO, who could ask for more?

Colin Clarke

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:5 (May/June 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.