This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

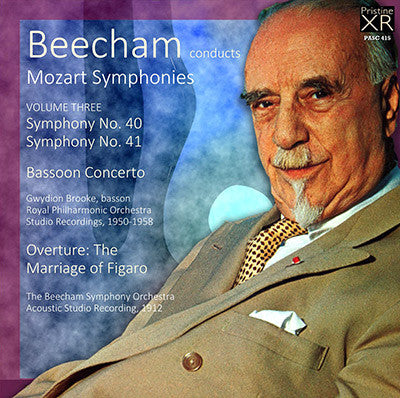

- Cover Art

Sir Thomas Beecham conducts Mozart Symphonies - the 1950s Columbia recordings

Third of three volumes, plus the Bassoon Concerto and Beecham's very first, 1912 Mozart recording

As with previous issues in this series, the symphony recordings here were made for American releases on the US Columbia label, which had long since cut its ties with its British namesake. Yet, unlike several of the Mozart symphony recordings Beecham made for US Columbia it was issued in the UK on EMI's Columbia subsidiary, which at the time was still a 78rpm-only operation. It is one of the few of this series that Beecham returned to EMI's Abbey Road studios later that decade to remake, the Columbia recordings having taken place in London's Kingsway Hall. The 1954 recording of the 40th Symphony, by contrast, found its British issue on the Philips label, two years after its recording. Beecham had previously recorded it with the London Philharmonic for EMI in 1937; this is his only other studio recording.

The two other recordings presented here almost serve to bookend the conductor's recorded career. The Bassoon Concerto was originally issued as a mono LP but was also recorded in stereo, and this is the version presented here from December 1958, and a very good hi-fi recording it is too; where the symphonies needed quite a lot of resurrecting, this was generally fine. By contrast, the 1912 recording of the overture to Figaro was his first outing with Mozart and from his second stint in the recording studio, having cut seven sides in 1910. This acoustic recording has been significantly updated in this XR remastering.

Andrew RoseFull Track Listing

-

MOZART Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K.550

Columbia ML-5194

Recorded Walthamstow Assembly Hall, 26 April 1954 -

MOZART Symphony No. 41 in C major, K.551, "Jupiter"

Columbia ML-4313

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 22 February 1950 -

MOZART Bassoon Concerto in B flat major, K.191

HMV ALP.1768, ASD.322

Recorded Abbey Road Studio 1, 18 December 1958

A stereo recording

Gwydion Brooke, bassoonRoyal Philharmonic Orchestra

Sir Thomas Beecham, conductor -

MOZART The Marriage of Figaro: Overture

Odeon X-84

Matrix number 76212, Lxx 3677

Recorded c. 1912

Beecham Symphony Orchestra

Sir Thomas Beecham, conductor

Fanfare Review

It always is vibrant and energizing, but never with a lack of feeling for color and nuance

At the lunch held for Thomas Beecham’s 70th birthday, congratulatory telegrams—including some from composers—were read to him. When the applause died down, Beecham asked gently, “Nothing from Mozart?” For all of Beecham’s renown as a conductor of Delius and Handel, Mozart was central to his repertory. Indeed, Beecham explored the heights and depths of Mozart, and Mozart in turn gave Beecham the most comprehensive avenue for displaying his artistry. Beecham said that Mozart introduced into music “an intimacy, a masculine tenderness, unique—something confiding, affectionate.” Beneath the conductor’s brilliant exterior, this was a quality Beecham shared with the composer, endearing him to his players and audiences. Beecham was one of the few conductors of his time to program large amounts of Mozart’s orchestral music, and, of that time, he presented Mozart with a full orchestra and a large sound, although never with sentimentality. He was noted for meticulously placing marks for expression in his players’ parts, so it is not surprising that, particularly in the two symphonies on this CD, one can hear an attention to detail rare in recordings of these works from any era. Beecham quipped that “a fine performance” required “the maximum of virility coupled with the maximum of delicacy.” The bawdy overtone notwithstanding, there is truth in this remark for Beecham’s Mozart. It always is vibrant and energizing, but never with a lack of feeling for color and nuance. For better or worse, it sounds like no one else’s Mozart.

Beecham starts the 40th Symphony at a quicker tempo than many of his contemporaries did. One immediately is struck by the orchestral sound’s beauty, as is true throughout both symphonies. A member of the Cleveland Orchestra commented on the simplicity of Beecham’s gestures in Mozart, which must have contributed to the gorgeous tone. The urgency of the RPO’s playing helps accentuate the first movement’s tragic sense. Beecham gives the Andante much room to breathe. It is full of the “masculine tenderness” Beecham describes. In the third movement, the orchestra’s sound, with its tragic nature, has overtones of Gluck. The trio, to use Beecham’s term, is “confiding.” The final movement features despair matched with exhilaration. The “Jupiter” on this CD is Beecham’s 1950 mono version, not his stereo remake. Its opening movement is lively, noble, and majestic. The slow movement is truly cantabile, with beautifully flowing, singing phrases. The whole has a domestic feeling, as if depicting Wolfgang alone with Constanze. A mixture of pomp and gentleness informs the third movement. The last movement is operatic in its scope and its multiplicity of gestures. It is of a piece with the ensemble that closes Don Giovanni. Beecham’s (and Mozart’s) zest for life is readily apparent.

The bassoon concerto receives the only stereo recording on the CD. Gwydion Brooke is a rich-toned and nimble soloist, with a distinctive sound. The uncredited cadenzas he uses play to the instrument’s gnomic quality. Beecham is a warm and sympathetic colleague. The 1912 recording of the Figaro overture, featuring the legendary Beecham Symphony Orchestra, demonstrates that Beecham at age 33 already possessed the drive, wit, and elegance that would characterize his whole career. Andrew Rose has done wonders remastering the two symphonies, which are in full-toned and beautifully balanced mono, while his version of the concerto represents the Abbey Road studio at its finest. He also has coaxed a highly listenable sound out of the 1912 acoustic overture. If you are looking for stereo CDs of the two symphonies, I would recommend Jeffrey Tate and Yehudi Menuhin. Beecham, however, is a law unto himself and deeply inspired. Perhaps we should give the conductor the last word. When Fritz Reiner came backstage to congratulate the conductor “on a wonderful evening of Beecham and Mozart,” Beecham replied, “Why drag Mozart into it?”

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:2 (Nov/Dec 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.