This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

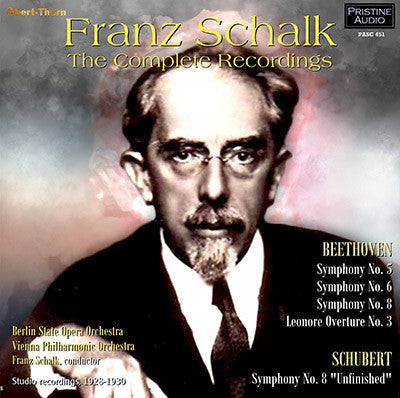

Franz Schalk - a distinguished conductor who recorded little: the complete recordings

"One

surely is left wishing for more. No one with an interest in performers

of a century ago, and in the dawn of electrical recording, could

possibly be without this release, nor could they fail to enjoy it" -

Fanfare

Those at all familiar with the name of Franz Schalk most likely associate it with the editing of critically-disparaged cut versions of Bruckner symphonies. This does a disservice, however, to his achievements in a long conducting career. Schalk was born in Vienna on May 27, 1863. He studied under Bruckner and violinist Joseph Hellmesberger, and after a series of conducting posts in increasingly important venues – from Bohemia to Graz (where he premiered Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony in 1894), Prague, Berlin, London’s Covent Garden and New York’s Metropolitan Opera – Mahler appointed him First Kapellmeister of the Vienna Court Opera in 1900.

For the next three decades, he reigned as one of the most important conductors in Vienna, heading the (renamed) State Opera from 1919 to 1929 (where Richard Strauss, whose Die Frau ohne Schatten Schalk premiered in 1919, was co-director for several years), leading the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde for 17 years, and serving as one of the driving forces in the postwar revival of the Salzburg Festival.

From the recorded evidence, Schalk favored swift, flowing tempi, with occasional slowing for rhetorical effect. In this, he was similar to other conductors of his generation such as Felix Weingartner (b.1863) and Richard Strauss (b.1864), musicians who came of age around the time of Wagner’s passing, and different from the more monumental approach favored by the following generation, including Otto Klemperer (b.1885) and Wilhelm Furtwängler (b.1886).

Schalk’s brief recording career began in 1928 with a Schubert Unfinished with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra for Odeon. (The 1927 date given in earlier reissues of this recording is incorrect.) The entire symphony was recorded in single takes on January 12th, but nothing from this session was issued. A remake session on March 2nd, with all takes listed as “2” was approved. (The issued version of Side 5, listed as “Take 3”, is a sonically compromised dubbing in all editions).

A month later, Schalk began a series of Beethoven recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic for HMV. Although that orchestra had previously made some acoustic recordings for Grammophon in 1924, these were its first electrical discs. Four sessions stretching over two weeks produced the Sixth and Eighth Symphonies and the Leonore Overture No. 3. A further session eighteen months later in October, 1929, followed by a makeup session the following January, was devoted to the Beethoven Fifth.

Schalk and the VPO were to go before the microphone one final

time, on April 16, 1931 to remake the most problematic of his earlier

recordings. The first side of the Beethoven Fifth, with its opening

ensemble imprecisions, was redone, as was the entire Beethoven Eighth,

whose 1928 recording was plagued with obtrusive low-frequency hum

(corrected in this transfer). Neither of these recordings were issued,

however. HMV’s reported plans to record Schalk in the Bruckner Third

and Fourth Symphonies came to naught with the conductor’s death on

September 3, 1931.

The sources for the transfers were Amercian Columbia “Viva-Tonal” pressings for the Schubert, British HMV shellacs for the Beethoven Sixth and Eighth, and red label 1930s German Electrola pressings for the Leonore Overture and the Beethoven Fifth (the latter with patches from British HMVs).

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

SCHUBERT: Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D759 ‘Unfinished’

Recorded 2 March 1928 in Berlin

Matrix nos.: XXB 7918-2, 7919-2, 7920-2, 7921-2, 7922-3 & 7923-2

First issued on Odeon O-8344/46

-

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68 ‘Pastoral’

Recorded 4, 11 & 12 April 1928 in the Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: Ck 2854-2, 2855-2, 2856-2, 2857-2, 2858-1, 2859-2, 2860-2, 2861-2, 2862-2 & 2863-2

First issued on HMV D 1473/7

-

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93

Recorded 12 – 13 April 1928 in the Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: Ck 2867-2, 2868-2, 2869-2, 2870-2, 2871-1 & 2872-1

First issued on HMV D 1481/3

-

BEETHOVEN: Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b

Recorded 13 April 1928 in the Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: Ck 2873-3, 2874-1, 2875-1 & 2876-1

First issued on Electrola EJ 332/3

-

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

Recorded 26 & 28 October 1929 and 27 January 1930 in the Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: CW 2881-2, 2882-1, 2883-4, 2884-2, 2887-4, 2888-2, 2889-2 & 2890-2

First issued on Electrola EH 620/3

Berlin State Opera Orchestra (Schubert)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (Beethoven)

Franz Schalk (conductor)

Fanfare Review

I find the Sixth Symphony superb, and the Leonora hardly less so

This is a somewhat unexpected release—unexpected because these are little-remembered recordings, but they remind us that the centenary Beethoven’s death, nearly nine decades ago, coincided roughly with the huge technological breakthrough of electrical recording. Record companies rushed to honor the composer with recordings of his music using the new and vastly improved recording method.

Weingartner recorded the Ninth Symphony in London in March 1926, Kreisler and Blech recorded the Violin Concerto in Berlin in December of that year, and Pfitzner, who had recorded the Schumann Fourth in Berlin, also in 1926, began his Beethoven symphony cycle with the First and Fourth Symphonies in 1928. By that year, electrical recording was well established in the German capital, when composer, editor, and conductor Franz Schalk made the first of his total of five recordings collected by Pristine on these two splendidly realized discs: the Schubert Eighth Symphony, for the Odeon label.

After making that recording on March 2, Schalk went to Vienna where, on April 4, the Vienna Philharmonic was first recorded by HMV using the no longer brand-new technology. We can’t know how much was accomplished at that first session, but between April 11 and 13, the Sixth and Eighth Symphonies and the Third Leonora Overture were committed to disc. The Fifth Symphony was recorded in sessions of October 1929 and January 1930. A year later a patch-up session (involving the Fifth’s first movement) resulted in nothing usable, or perhaps better put, nothing superior to what had already been recorded. Although there were plans to record more (Bruckner, in fact), Schalk’s death, at only age 68, in September 1931 put an abrupt end to what might have been a promising recording career.

All the more credit to Schalk, then, that his small recorded legacy is so distinguished, and to Pristine and in particular to Mark Obert-Thorn for his superlative restorations. Pristine’s Andrew Rose, in addition to providing the aegis for this set, also takes credit for correcting some pitch problems in the Schubert. The sound is easily listenable throughout. To ears which are attuned to the sonic capabilities of 21st-century technology, it is a bit distant and lacking in impact. The Schubert, however, is entirely the equal of what Obert-Thorn achieved with Kreisler’s Beethoven and Mendelssohn (Naxos), and what others accomplished with the Berlin recordings by Pfitzner. The Vienna recordings are rather soft-textured in their tonal quality. That robs the Fifth of some impact, in comparison to other and later recordings, but suits the “Pastoral” extremely well. The overture, arguably the most dramatic of these readings, comes through well, as does in particular the finale of the Eighth.

As to the performances, I find the Sixth Symphony superb, and the Leonora hardly less so. The playing of the VPO of that era is particularly beautiful in the “Pastoral,” with its numerous opportunities for woodwind and other solo display, and the overture is a taut, disciplined reading which builds up in excitement to a splendid call by the solo trumpet. Not for Schalk the drive of Toscanini, nor the broad and sometimes granitic strokes of some of his German colleagues. His performances are modern sounding, clean-limbed, and remind me more of Weingartner’s Beethoven than any other. Take that as high praise. The Eighth is a fine performance, most energetic and distinctive in the first and last movements. In the Fifth, tempos are well chosen and the transition to the final movement well managed, but—perhaps due in part to sonics—one might wish for a bit more force, more drive.

One surely is left wishing for more. The planned Bruckner recordings, Brahms, Schumann are all surely composers where we might have learned from Schalk’s insights. In the spirit of being grateful for what we have, thanks, once again, to Pristine, to Obert-Thorn and Rose for these particularly successful reissues. No one with an interest in performers of a century ago, and in the dawn of electrical recording, could possibly be without this release, nor could they fail to enjoy it.

James Forrest

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:5 (May/June 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.