This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

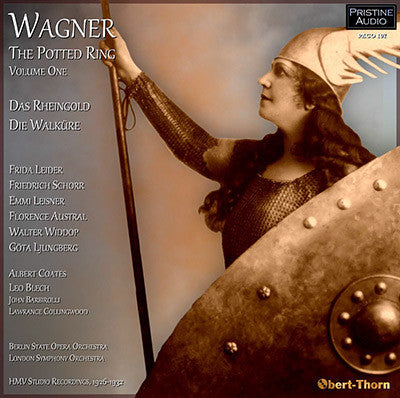

HMV's Potted Ring, Volume 1: Das Rheingold and Die Walküre

"This is a set no enquiring Wagnerian, whatever complete version of The Ring he or she owns, should be without" - Gramophone

The present release is the first of three which will bring together the 122 78 rpm sides of extended excerpts from Wagner’s tetralogy which His Master’s Voice recorded in London, Berlin and Vienna between 1926 and 1932. The scope of this project centers around the Ring albums – not every disc of music from the Ring which HMV issued during this period. It is, however, “more than complete” in that two HMV recordings which were not part of the Ring albums, but which feature some of the same performers, have been added: Coates’ Rhinegold Prelude, and Schorr’s Wotan/Fricka duet with Leisner from Act 2 of Die Walküre. The present volume gathers together excerpts from Das Rheingold and Die Walküre; the second will focus on Melchior’s Siegfried recordings; and the final one will feature scenes from Götterdämmerung, as well as an appendix featuring alternate recordings from the series and an outline of motives from the Ring cycle.

While Rheingold got rather short shrift in HMVs plans (only two discs in an album otherwise devoted to Siegfried excerpts), more attention was paid to Die Walküre. The sessions were split between a Berlin cast centering around the Brunnhilde of Frida Leider and the Wotan of Friedrich Schorr, conducted by Leo Blech, and a London cast with Walter Widdop as Siegmund and Florence Austral singing Brunnhilde, primarily led by Albert Coates. Göta Ljungberg appeared as Sieglinde in both, save for a single London side. The Act 1 excerpts were all made in London, while Act 3 was done in Berlin and the second act split between the two.

The recordings capture Leider and Schorr, both considered the finest exponents of their roles at the time (and certainly among the finest of all time), at the height of their powers. A decade later, when Kirsten Flagstad came on the international scene, she was invariably compared to Leider, and not always to the latter’s detriment. And while later singers could bring more psychological complexity to Wotan (Hans Hotter, for example), few could match the combination of legato and authoritative declamation that Schorr brings to the role.

The original recording quality is variable, coming as it does within a couple years of the introduction of electrical recording. The London sessions were distantly miked in large halls, and the singers are often overwhelmed by Coates’ surging orchestra. Some of the Berlin sides can also sound rather dim, depending on the engineering of a particular session. Multiple copies of the finest pressings on which these discs were available (prewar American Victor “Z” and “Gold” label editions) were drawn upon for the present transfers, except for one Rheingold disc which only came out on HMV.

Mark Obert-Thorn

HMV's Potted Ring, Volume 2: Siegfried

"This is a set no enquiring Wagnerian, whatever complete version of The Ring he or she owns, should be without" - Gramophone

The present release is the second of three which will bring together the 122 78 rpm sides of extended excerpts from Wagner’s tetralogy which His Master’s Voice recorded in London, Berlin and Vienna between 1926 and 1932. The scope of this project centers around the Ring albums – not every disc of music from the Ring which HMV issued during this period. The first volume (PACO107) gathered together excerpts from Das Rheingold and Die Walküre; the present set focuses on Melchior’s Siegfried recordings; and the final one will feature scenes from Götterdämmerung, as well as an appendix featuring alternate recordings from the series and an outline of motives from the Ring cycle.

The Siegfried recordings have a particularly convoluted history in the “Potted Ring” saga. Initially, HMV released an album of eight discs, combining two from Das Rheingold (featured in Volume 1 of our series) with six from Siegfried, in recordings made between June, 1927 and April, 1928. This set included the Wotan/Erda duet featured here (the only “Potted Ring” recordings to come from Vienna), as well as six sides with Rudolf Laubenthal as Siegfried. In three of these, he was joined by Frida Leider in excerpts from the final duet. (Oddly, a disc with an orchestral version of the “Forest Murmurs” led by Leo Blech was included along with Laubenthal’s vocal excerpts from the same scene.)

Melchior’s absence from these sides can be explained by the fact that

he did not make his first recordings for the HMV labels until June,

1928. In May of the following year, sessions were scheduled in London

for him to record Siegfried selections under Albert Coates,

including re-recordings of material already covered in Laubenthal’s solo

sides. These were collected into a second, five disc volume on HMV.

Further recordings in May, 1930 (“Selige Öde” and “Das ist kein Mann”)

under Robert Heger were issued on two single discs. In America, Victor

collected these, the 1929 recordings and the unduplicated 1927-28 Siegfried sides from the first volume in a ten-disc set.

Further recordings of excerpts from Acts 1 and 2 in May, 1931 and the Act 3 duet in May, 1932, all under Heger, were issued as separate volumes both in Europe and America. Ultimately, HMV released a 19-disc set of the 37 sides presented here, although it was never offered this way on Victor. Fortunately for posterity, Melchior’s unsurpassed assumption of the rôle was captured nearly complete at the height of his considerable powers in these recordings.

The sources for the transfers were multiple copies of American Victor

editions: prewar “Z” and “Gold” label pressings, as well as a

particularly quiet postwar album, for the 1928-30 recordings; “Z” and

“Gold” editions for the 1931 recordings; and two sets of “Z” pressings

for the 1932 final scene. The progress of electrical recording during

this period can be traced through the variable sound of the originals,

from the dim Vienna sides of 1928 and the occasionally strident and

overloaded London sessions of 1929, to the warm, detailed sound obtained

in Abbey Road in 1932.

Mark Obert-Thorn

HMV's Potted Ring, Volume 3: Götterdämmerung, Motives and Extras

"We

encounter truly great Wagner singing ... Laubenthal’s Siegfried is not

far short of ideal ... Andresen sings with the kind of firm, black tone

simply not encountered today"

- Alan Blyth, Opera on Record (1979)

This third and final volume of our “Potted Ring” series centers on Götterdämmerung, whose recording, like the earlier Walküre set, was divided between London and Berlin, with different casts, conductors and orchestras. I have interpolated two recordings not contained in the original sets in order to make the performance more complete. First, by including the first side of Coates’ “Rhine Journey” (missing in the albums) and editing it around “Zu neuen Taten”, I have been able to present the Prologue uncut. Secondly, I have included the Melchior/Schorr recording of “Hast du, Gunther, ein Weib?” in order to fill in a scene which went unrecorded in the original albums, one which leads directly into Hagen’s Watch (and one which I did not originally include in my 1994 “Potted Ring” set for Pearl).

The Appendix contains several recordings from the HMV and Electrola editions of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung which were replaced in the versions issued by Victor in America. The six sides with Laubenthal (three of them with Leider), as well as Blech’s orchestral version of the “Forest Murmurs”, were contained in the first album of Siegfried excerpts issued in Europe. By the time Victor issued their first Siegfried set, several sides had been re-recorded with Melchior, and these were chosen for the American release, although the abridged final scene with Laubenthal and Leider was retained. Eventually, Melchior recorded the complete scene; and since that appears in Volume 2 of our series, these duplicated earlier sides are presented here.

Muck’s “Rhine Journey” and “Funeral Music” appeared in the European editions of the Götterdämmerung albums, but Victor replaced them with the Coates recordings. As Coates conducts the rest of the Prologue and most of the Immolation Scene, I thought it would be more consistent to go with the Victor choices here and put the Muck versions in the Appendix. Finally, the two discs of illustrated motives from the Ring cycle were not originally part of any set, but were issued separately. Two different, uncredited announcers are heard. The first sounds like a seasoned BBC presenter; but I have often wondered whether the second might be producer/conductor Collingwood himself.

The sources for the transfers were American Victor editions (primarily “Z” pressings) for everything except the Melchior/Schorr duet, the three Laubenthal Siegfried solos, Blech’s “Rhine Journey”, a portion of the end of Act 2 of Götterdämmerung, and the side with “Schweigt eures Jammers” (dubbed on Victor), which all came from British HMV pressings.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

CD 1 (76:13)

WAGNER Das Rheingold WWV 86A

1. Prelude (4:01)

Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert CoatesRecorded 2 February 1926, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 142-1 ∙ HMV D 1088

2. Spottet nur zu! (4:44)

Louise Trenton, sop.; Elsie Suddaby, sop.; Nellie Walker, con.; Arthur Fear, bs.

3. Wotan, Gemahl (4:46)

Nellie Walker, con.; Walter Widdop, ten.; Kennedy MacKenna, ten.; Howard Fry, bar.; Arthur Fear, bs.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 5 January 1928, Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 1540-3/1541-2B ∙ HMV D 1546

4. Zur Burg führt die Brücke … Abendlich strahlt (8:32)

Friedrich Schorr, bar.; Waldemar Henke, ten.; Genia Guszalewicz, con.

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo BlechRecorded 17 June 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CDR 4700-2/4701-3 ∙ HMV D 1319

WAGNER Die Walküre WWV 86B

Act 1

5. Prelude . . . Wes Herd dies auch sei (4:03)

Recorded 26 August 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1485-1A ∙ HMV D 13206. Ein Schwert verhieß mir der Vater (4:26)

Recorded 23 August 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1467-1A ∙ HMV D 13207. Schläfst du, Gast? (0:45)

8. Der Männer Sippe (3:51)

Recorded 27 May 1927, Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1367-1A ∙ HMV D 13219. Dich, selige Frau (1:05)

10. Winterstürme wichen dem Wonnemond (2:46)

Recorded 23 August 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1465-2 ∙ HMV D 1321London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

11. Du bist der Lenz (7:51)

Recorded 16 August 1926, London ∙ Matrices: CR 611-2A/613-1 ∙ HMV D 1322Orchestra ∙ Lawrance Collingwood

12. Siegmund heiß ich (3:12)

Recorded 23 August 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1466-2A ∙ HMV D 1323London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Walter Widdop, ten.; Göta Ljungberg, sop.

Act 2

13. Prelude . . . Nun zäume dein Roß . . . Hojotoho! (4:14)

Recorded 12 September 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrix: CwR 1116-2 ∙ HMV D 1323Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo Blech

14. Der alte Sturm, die alte Müh! (4:38)

15. So ist es den aus mit den ewigen Göttern (8:06)

16. Was verlangst du? (4:51)

Recorded April, 1932, Abbey Road Studio 1, London ∙ Matrices: 2B2840-2/2841-1/2842-2/2843-1 ∙ HMV DB 1720/21London Symphony Orchestra ∙ John Barbirolli

17. O heilige Schmach! (4:20)

Recorded 12 September 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrix: CwR 1117-2 ∙ HMV D 1324Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo Blech

Frida Leider, sop.; Emmi Leisner, m-s.; Friedrich Schorr, bar.

-

CD 2 (76:58)

Die WalküreAct 2 (continued)

1. So nimm meinen Segen (4:13)

Recorded 12 September 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrix: CwR 1118-1 ∙ HMV D 1324Frida Leider, sop.; Friedrich Schorr, bar.

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo Blech

2. Raste nun hier (3:01)

3. Hinweg! Hinweg! (5:53)

Recorded 27 May 1927, Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 1368-2/1369-1 ∙ HMV D 13254. Siegmund! Sieh auf mich! (4:53)

Recorded 23 August 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1462-1 ∙ HMV D 13265. Fänd’ich in Walhall (4:21)

6. So jung und schön (3:29)

Recorded 26 August 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 1483-1A/1484-1A ∙ HMV D 1326/277. Zauberfest bezähmt ein Schlaf (4:38)

Recorded 25 October 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1463-3 ∙ HMV D 13288. Wehwalt! Wehwalt! (2:31)

9. Geh hin, Knecht! (1:46)

Recorded 23 August 1927, Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1464-1A ∙ HMV D 1328Walter Widdop, ten.; Göta Ljungberg, sop.; Florence Austral, sop.; Louise Trenton, sop.; Howard Fry, bar.

(Note: Trenton sings Sieglinde on CR 1463 only, while Fry sings both Hunding and Wotan on CR 1464)

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Act 3

10. Prelude . . . Hojotoho! (6:55)

Recorded October, 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CwR 1163-6/1164-2 ∙ HMV 132911. Rette mich, Kühne! (3:45)

Recorded 1 November 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrix: CwR 1188-2 ∙ HMV 132712. Wo ist Brünnhild’ (8:46)

Recorded October, 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CwR 1161-2/1162-1 ∙ HMV 133013. War es so schmählich (3:31)

Recorded 1 November 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrix: CwR 1190-5 ∙ HMV 133114. Du zeugtest ein edles Geschlecht (3:46)

Recorded 29 September 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrix: CwR 1189-3 ∙ HMV 133115. Leb wohl, du kühnes, herrliches Kind! (3:59)

16. Der Augen leuchtendes Paar (6:35)

17. Loge, hör! (4:54)

Recorded 17 June 1927, Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CDR 4695-1/4696-2/4697-1/4698-1 ∙ HMV D 1332/33Frida Leider, sop.; Friedrich Schorr, bar.; Göta Ljungberg, sop.; (Valkyries: Ljungberg; Elfriede Marherr; Genia Guszalewicz; Alberti; Lydia Kindermann)

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo Blech

WAGNER Siegfried

CD 1

Act 1

1 Prelude

2 Zwangwolle Plage!

3 Hoiho! Hoiho! Hau ein! Hau ein!

4 Als zullendes Kind zog ich dich auf

5 Soll ich der Kunde glauben

6 Aus dem Wald fort

7 Heil dir, weiser Schmied!

8 Dein Haupt pfänd’ ich

Heinrich Tessmer, ten.; Lauritz Melchior, ten.; Friedrich Schorr, bar.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Robert Heger

Recorded 9 May 1931 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: 2B 529-1A/528-2/531-2/532-2A/533-2A/534-1A/525-1A/526-2 ∙ HMV DB 1713 and DB 1578/81

9 Fühltest du nie im finstren Wald

10 Nothung! Nothung! Neidliches Schwert!

11 Hoho! Hoho! Hahei! Schmiede, mein Hammer

Albert Reiss, ten.; Lauritz Melchior, ten.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 16/17 May 1929 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 2197-3/2198-2B/2199-3A/2200-2 ∙ HMV D 1690/1

Act 2

12 In Wald und Nacht

13 Zur Neidhöhle fuhr ich bei Nacht

14 Deine Hand hieltest du vom Hort?

Eduard Habich, bar.; Friedrich Schorr, bar.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Robert Heger

Recorded 21 May 1931 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: 2B 554-2/555-2 ∙ HMV DB 1582

15 Daß der mein Vater nicht ist

16 Du holdes Voglein!

Lauritz Mechior, ten.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 17 May 1929 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 2401-2/2402-2A ∙ HMV D 1692

17 Haha! Da hätte mein Lied

18 Wohin schleichst du eilig und schlau

Lauritz Melchior, ten.; Heinrich Tessmer, ten.; Eduard Habich, bar.*

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Robert Heger

Recorded 21 May 1931 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: 2B 557-1A/556-2 ∙ HMV DB 1583

*(Note: Habich sings both Fafner and Alberich)

CD 2

Act 2 (continued)

1 Da lieg auch du, dunkler Wurm!

2 Gönntest du mir wohl ein gut Gesell?

3 Hei! Siegfried erschlug nun den schlimmen Zwerg!

Lauritz Melchior, ten.; Nora Gruhn, sop.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 29 & 17 May 1929 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 2404-2B/2403-1 ∙ HMV D 1693

Act 3

4 Prelude

5 Wache, Wala!

6 Stark ruft das Lied

7 Dir Unweisen ruf’ ich ins Ohr

Emil Schipper, bar.; Maria Olszewska, con.

Vienna State Opera Orchestra ∙ Karl Alwin

Recorded 20 & 26 April 1928 in Vienna ∙ Matrices: CK 2939-2/2899-1/2900-2/2938-1 ∙ HMV D 1533/4

8 Kenntest du mich, kühner Sproß

9 Zieh hin!

10 Siegfried mounts the rocky height

Rudolf Bockelmann, bar.; Lauritz Melchior, ten.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 22 May 1929 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 2405-3/2406-2 ∙ HMV D 1694

11 Selige Öde auf sonniger Höh’!

12 Das ist kein Mann!

Lauritz Melchior, ten.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Robert Heger

Recorded 12 May 1930 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 2498-3/2499-1/2500-1 ∙ HMV D 1836/7

13 Heil dir, Sonne!

14 O Siegfried! Siegfried!

15 Ewig war ich

16 Dich lieb’ ich

17 Ob jetzt ich dein?

Florence Easton, sop.; Lauritz Melchior, ten.

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden ∙ Robert Heger

Recorded 29 May 1932 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London ∙ Matrices: 2B 2896-2/2897-1B/2898-2/2899-2B/2900-2/2901-1B/2902-1B ∙ HMV DB 1710/3

WAGNER Götterdämmerung

CD 1

Prologue

1 Welch Licht leuchtet dort?

Noel Eadie, sop.; Evelyn Arden, sop.; Gladys Palmer, con.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 17 October 1928 and 3 January 1929 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: Cc 13724-2/13725-1A/13726-5/13727-5A ∙ HMV D 1572/3

2 Dawn

Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 26 January 1926 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 136-3 [part] ∙ HMV D 1080

3 Zu neuen Taten

Florence Austral, sop.; Walter Widdop, ten.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 18 October 1928 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: Cc 13730-2/13731-3 ∙ HMV D 1574

4 Siegfried’s Rhine Journey

Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 26 January 1926 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 136-3 [part]/137-1 ∙ HMV D 1080

Act 1

5 Begrüße froh, o Held

Arthur Fear, bar.; Walter Widdop, ten.; Frederic Collier, bs.; Göta Ljungberg, sop.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 10 October 1928 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrix: Cc 13699-1 ∙ HMV D 1575

6 Hast du, Gunther, ein Weib?

Lauritz Melchior, ten.; Friedrich Schorr, bar.; Rudolf Watzke, bs.; Lieselotte Krumrey-Topas, sop.

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo Blech

Recorded 15 June 1929 in the Philharmonie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CLR 5458-2A/5459-1A ∙ HMV D 1700

7 Hier sitz’ ich zur Wacht

Ivar Andrésen, bs.

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Fritz Zweig (credited to Leo Blech on label)

Recorded 17 February 1928 in the Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrix: CLR 3883-1 ∙ HMV D 1576

8 Seit er von dir geschieden

Maartje Offers, con.; Florence Austral, sop.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 23 August and 25 October 1927 in Queen’s Hall, London and 16 February 1928 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 1460-3A/1461-2/1473-3/1474-3 ∙ HMV D 1576/8

CD 2

Act 2

1 Hoiho! Hoihohoho!

Ivar Andrésen, bs.

Berlin State Opera Orchestra and Chorus ∙ Leo Blech

Recorded 21 June 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CDR 4708-2/4709-1 ∙ HMV D 1578/9

2 Helle Wehr!

Walter Widdop, ten.; Florence Austral, sop.; Chorus

Recorded 17 October 1928 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrix: Cc 13728-3A ∙ HMV D 1579

3 Welches Unholds List

Florence Austral, sop.; Frederic Collier, bs.; Arthur Fear, bar.

Recorded 18 October 1928 in Kingsway Hall, London ∙ Matrices: Cc 13732-2A/13733-2/13734-1 ∙ HMV D 1580/1

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Act 3

4 Frau Sonne sendet lichte Strahlen

Tilly De Garmo, sop.; Lydia Kindermann, sop.; Elfriede Marherr, con.; Rudolf Laubenthal, ten.

Recorded 10 September 1928 in the Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CLR 4488-1/4489-1/4490-2/4491-2 ∙ HMV D 1581/3

5 Mime heiß ein mürrischer Zwerg

6 Brünnhilde, heilige Braut!

Rudolf Laubenthal, ten.; Desider Zador, bar.; Emmanuel List, bs.; Berlin State Opera Chorus

Recorded 7 September 1928 in the Singakademie, Berlin ∙ Matrices: CLR 4482-2/4483-1/4484-1 ∙ HMV D 1583/4

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo Blech

7 Siegfried’s Funeral Music

Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 26 January and 26 March 1926 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 217-2/141-3 ∙ HMV D 1092

8 Schweigt eures Jammers

9 Starke Scheite schichtet mir dort

Florence Austral, sop.; Göta Ljungberg, sop.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Lawrance Collingwood

Recorded 1 December 1927 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrix: CR 1472-3A ∙ HMV D 1586

10 Sein Roß führet daher

11 Ruhe, ruhe, du Gott!

12 Finale

Florence Austral, sop.

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Albert Coates

Recorded 25/26 August and 25 October 1927 in Queen’s Hall, London ∙ Matrices: CR 1486-3/1487-1/1475-2 ∙ HMV D 1586/7

CD 3: APPENDIX

1 – 90 90 Motives from The Ring (see booklet for details)

London Symphony Orchestra ∙ Lawrance Collingwood

Recorded 17 April and 23 May 1931 in Kingsway Hall, London, Matrix nos.: 2B 504-2A/505-2A/562-1A/563-1A ∙ HMV C 2237/8

DOWNLOAD MOTIVES SCORE by clicking HERE

SIEGFRIED

Act I

91 Nothung! Nothung!

Recorded 25 August 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1058-1 ∙ HMV D 1530

Act II

92 Daß der mein Vater nicht ist

Recorded 25 August 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1059-2 ∙ HMV D 1530

93 Forest Murmurs

Recorded 26 June 1928 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix nos.: CLR 4305-2/4306-2 ∙ HMV D 1531

94 Heiß ward mir

Recorded 25 August 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1060-2 ∙ HMV D 1532

Act III

95 Heil dir, Sonne!

Recorded 27 August 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1064-2 ∙ HMV D 1532

96 Ewig war ich

Recorded 27 August 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1065-2 ∙ HMV D 1535

97 O Siegfried! Dein war ich von je!

Recorded 27 August 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1066-1 ∙ HMV D 1535

Frida Leider (soprano) (Tracks 95 – 97)

Rudolf Laubenthal (tenor) (Tracks 91, 92, 94 – 97)

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Leo Blech

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG

Prologue

98 Siegfried’s Rhine Journey (4:24)

Recorded 10 December 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1418-2 ∙ HMV D 1575

Act III

99 Siegfried’s Funeral Music (8:04)

Recorded 10 December 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin. Matrix no.: CwR 1419-3A/1420-2A ∙ HMV D 1585

Berlin State Opera Orchestra ∙ Karl Muck

MusicWeb International Review

There are some singers here whose natural abilities still match or even transcend anything we can hear today

REVIEW OF VOLUME 3

It may be perverse, but it makes some sense to deal in the first

instance with the supplementary disc provided here containing the

Appendices. Just over half of this disc consists of six excerpts from Siegfried

featuring Rudolf Laubenthal, which were jettisoned from the original

78rpm boxes in favour of the tracks featuring Lauritz Melchior which

were issued by Pristine as Volume 2 of their ‘potted Ring’. One can see

the reasons for the substitution; Melchior was, as I have observed in my review of Volume 2, the most recommendable feature of the Siegfried

recordings, and moreover the excerpts given there were much less

truncated than those here. Nor is Laubenthal anything like as impressive

as Melchior, sounding unpleasantly strained in the more strenuous

passages of the role; and although Frida Leider is excellent as

Brünnhilde in the extracts from the final love duet, the massive

omissions from the score do much to vitiate the viability of what we are

given here.

Nor does the singing on the first CD of Götterdämmerung

do much to substantiate the often-trumpeted notion of the 1920s and

1930s as a ‘golden age’ of Wagnerian singing. The Prologue, briskly

despatched by Coates, features a trio of Norns none of whom would pass

muster today and in particular the pipingly small-voiced Noel Eadie who

completely fails to engender any sense of drama as the scene moves

towards its climax. When the lovers finally appear, Florence Austral and

Walter Widdop seem to be flailing frantically to keep up with the

headlong pace that is set for them by Albert Coates; and once the

curtain has descended, he despatches the Rhine Journey at a speed that

would give the Flying Dutchman pause for thought. Even Alan Blyth,

normally an admirer of this conductor, describes his pace here as

“ridiculously fast.” Nor, when we reach the Gibichung court, do things

improve much, since neither Arthur Fear and Frederic Collier begin to

come to terms with the dramatic element of their characters and it is

left to Göta Ljungberg in her few phrases to supply an element of vocal

distinction.

The record containing the oath of blood

brotherhood did not form part of the original boxed set of 78s but was

clearly intended to fill in a gap in the plot which would otherwise have

existed, and here everything suddenly comes to life. Lauritz Melchior

and Friedrich Schorr make an ideal coupling, and the excerpt here leads

nicely into Hagen’s Watch which is given a performance by Ivan Andrésen

which is quite simply superlative, encompassing the lowest notes with

ease and producing tone and diction which are black as night. He is

equally good in the high notes of his summoning of the vassals (slightly

cut) where the chorus respond superbly to his call, although no attempt

is made to comply with Wagner’s request for a smaller number of voices

in the opening section. Before that, at the end of the first CD, we have

heard a solidly contralto performance of Waltraute’s scene from Maartie

Offers, although she displays distinct signs of uneasiness on her

highest notes, some of which she truncates very abruptly. This excerpt

goes on through the exchanges with Brünnhilde, only concluding on the

entry of this disguised Siegfried. Albert Coates takes surprisingly slow

tempos throughout this scene, except in the passage describing Wotan’s

felling of the World Ash Tree which takes on a sudden spurt of energy

which verges on the jaunty. One suspects that this, and perhaps other

unexpectedly fast tempi, may have been conditioned by the need to fit

the music onto one side of a 78rpm record.

Widdop and Austral

are efficient rather than exciting in their taking of their conflicting

oaths, and the trio which concludes the Second Act relies largely on

Austral to generate much sense of drama although Collier and Fear are in

better voice than before. The opening scene of Act One (complete with a

niggling cut of some ten bars) suffers from a totally unengaged trio of

Rhinemaidens. Their warning to Siegfried of the curse on the Ring is so

dismally unthreatening that one can hardly blame the hero for ignoring

them. Laubenthal is in better voice here than in Siegfried, with less

purely heldentenor tones required for the delivery of his narration.

Here we are given the interjections of the vassals with the solo voice

that Wagner designates, but it sounds as though the lines are given to

Desider Zador as Gunther – which can be the only explanation that the

one tenor vassal’s lines are simply omitted. Alan Blyth describes this

recording of the narration as “one of the most clearly balanced 78s I

have ever heard” – and although Mark Obert-Thorn has done wonders with

the sound throughout, it is true nonetheless that this section has a

presence that one might well expect from a mono recording made more than

twenty years later. Leo Blech is an excellent conductor in these

sections, with a greater sense of moderation in speed than Coates. But

then Coates also springs a surprise with a very measured account of the

Funeral March, although an editing quirk introduces a couple of

additional timpani beats just after the march begins (presumably the

result of combining two different takes).

Florence Austral’s

Immolation Scene suffers from a similar combination of material from two

sessions, her voice sounding very much more distant at the beginning

than at the end. There is also an inexcusable cut of some fifteen bars

before the line “Ruhe, ruhe, du Gott!” which is all the more galling

when one realises that this omission comes at the expense of the

exchange between Brünnhilde and Gutrune which precedes the scene itself,

and which is not helped by a very underpowered delivery by Ljungberg

(or maybe she was just too far away from the microphones). We hear the

voice of Hagen (uncredited) at the end, and I am pleased to note that he

really sings his line “Give back the Ring” rather than shouting as so

many modern exponents of the role do.

Coates thankfully avoids

any sense of rush in the closing pages, but he does adopt the bad habit

of making an unmarked ‘air pause’ before the last ten bars and the final

chord is truncated rather abruptly. In the earlier part of the scene,

despite the inferior recording, Lawrence Collingwood takes a properly

measured and dignified approach.

Collingwood is also

responsible for the delivery of the brief snippets of leitmotifs on the

Appendix CD (which was originally issued on 78s separately). Each of

these is preceded by an announcer giving a number, which refers the

listener to the booklet where an explanation of each motif is given.

This may have been valuable to audiences at the time, but it hardly

comes up to the standards of Deryck Cooke’s marvellous exposition of

Wagner’s compositional methods on his 2-CD lecture which originally

accompanied Solti’s Ring (it remains available separately, as well as in

the Decca luxury limited edition). The identification of the numbered

motifs here also leaves much to be desired, with the principal love

theme described as ‘Flight’ in accordance with Walzogen’s original error

in his analysis published during Wagner’s lifetime and criticised by

the composer for its inaccuracies. The two other tracks on the Appendix

CD contain performances of the two orchestral sections of

Götterdämmerung which were superseded in the 78rpm boxed sets; but they

have a particular interest in that they are conducted by the veteran

Wagnerian Karl Muck, whose association with Bayreuth extended back to

the nineteenth century. Both extracts are truncated rather curiously,

just coming to a halt before the music actually stops. In the main set

the Funeral march is provided with a concert conclusion, but otherwise

the excerpts stick to Wagner’s operatic score. There are some other

points of historical interest, such as a bass trumpet which is clearly

not the valved trombone that one finds used on other recordings of the

period; and the cowhorns in the summoning of the vassals are simply

trombones and not the specially constructed instruments that were at

that stage still employed at Bayreuth.

I have had much pleasure

in reviewing the seven CDs that Pristine have produced over the last

year enshrining what has been described as the “Old Testament” of

Wagnerian interpretation in the period immediately following the First

World War. There are some singers here whose natural abilities still

match or even transcend anything we can hear today; but it has to be

said that the much-admired conducting of Albert Coates hardly bears

scrutiny on the basis of these recordings, and the same could be said

for a good deal of the singing in minor roles. Even as late as the 1950s

live performances of The Ring show a propensity for performers to make

mistakes which would hardly be tolerated today (see the Clemens Kraus

Bayreuth Ring for an example, riddled with horrific errors of various

sorts) but on these discs, without presumably much opportunity for

retakes, the performers display a sense of security which is admirable. I

note with some surprise the manner in which the singers slow down for

cadences at the end of phrases to an extent which might occasion comment

today, although Wagner does not always seem to expect them to do so;

one wonders to what degree he accepted this in his own performances?

Those who have an interest in such matters, as well as those who would

like to encounter a sense of vocal history in the making, are earnestly

recommended to hear these discs, with transfers which are unlikely ever

to be bettered.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

MusicWeb International, July 2015