- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

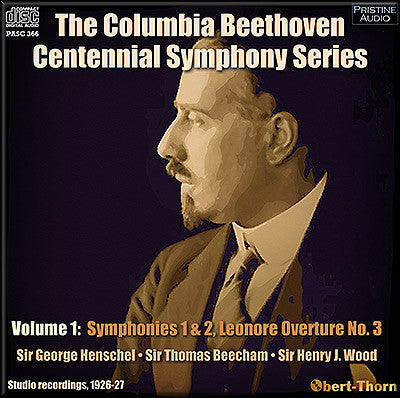

- Cover Art

Fanfare Review

I thought it exhilarating

REVIEW OF VOLUME 5

This concludes Pristine’s CD issue of

the first complete cycle of the Beethoven symphonies to be recorded

electrically. The series coincided with the centennial of Beethoven’s

1827 death. Actually, the Ninth was the first to be recorded and

replaced an acoustic recording of the piece by Weingartner that was

abandoned when electrical recording arrived. According to

He recorded the symphony a second time in 1935 with the Vienna Philharmonic, and it was those 78s that I learned the piece on. The performances are quite similar with two exceptions: The 1927 one, like two other early Ninths (Coates and Stokowski) is sung in English, and he takes the finale faster on the earlier recording. The faster tempo bothered me not a bit; in fact, I thought it exhilarating and, while the English text, often incomprehensible, is no asset, the soloists are quite good—Harold Williams still sounds like himself 20 years later. It seems to me that, perhaps due to the use of a slightly smaller string section and/or “tighter” acoustics, more inner detail is heard on the 1927 recording than on the later one. These two Weingartners, needless to say, have been surpassed sonically through the years, but in their straightforward, no-nonsense directness, they still hold up very nicely as performances, per se. and I’m delighted to have them both.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:5 (May/June 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.