- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

The complete Max Fiedler - a direct link back to Johannes Brahms

Double album of superb new transfers for

The B flat concerto set has an interesting history. Originally recorded over three days in June of 1939 with four takes made for nearly every side, Ney was unhappy with some of the results, and wrote to the conductor in the fall of that year about scheduling a remake session. Fiedler was on tour in Stockholm at the time, and replied that it would have to wait until his return. However, his death there in December of that year appeared to doom the project.

Ultimately, Grammophon scheduled a session for April of the following year with a “ghost” conductor (who remains unknown, although Alois Melichar has been suggested as a likely suspect). Five of the twelve sides were done over, with the original Fiedler-conducted takes remaining on Side 3 of the first movement (CD 2, Track 3, 8:41 to 13:11), all of the second and third movements, and the first side of the fourth movement (to 3:18 on Track 6). As far as I am aware, this is the first release to acknowledge the extent of Fiedler’s participation.

Multiple sources were assembled for each recording, and the best portions of each were used for transfer. The overture and the Fourth Symphony came from laminated American Brunswicks; the Second Symphony mostly from black label 1930s Polydor pressings; and the concerto from three different 1940s Grammophon and Polydor editions. Even so, some inescapable noise and distortion inherent in the original recordings remain.

-

BRAHMS Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80

Recorded 1931

Matrix nos: 1171 and 1172 bi

First published on Grammophon 27271 -

BRAHMS Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

Recorded 1931

Matrix nos.: 1162 ½, 1163 ½, 1164½ 1165 ½, 1166, 1167½, 1168, 1169 and 1170 bi

First published on Grammophon 95453 through 95457 -

BRAHMS Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98*

Recorded 1930

Matrix nos.: 993, 994, 995 ½, 1001, 997 ½, 998½, 999, 1000, 1002 ½, 1003 ¾ and 1004 ½ bi

First issued on Grammophon 95356 through 95361.

Additional pitch stabilisation:Andrew Rose -

BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 83

Recorded 1, 2 & 5 June 1939 and 29 April 1940

Matrix nos.: 14704, 14712, 11393, 14744, 11414, 11424, 11433, 11443, 11453, 11464, 14721 and 14734 GS 9

First issued on Grammophon 67566 through 67571

Elly Ney piano

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

*Berlin State Opera Orchestra

Max Fiedler conductor

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer:

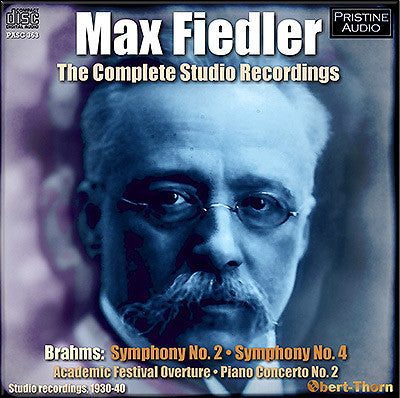

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Max Fiedler

Total duration: 2hr 19:46

Fanfare Review

No matter which performers of Brahms you prefer, I doubt you will hear the composer the same way after listening to Fiedler.

Historically, the present recordings are very

important. Max Fiedler, born in 1859, is one of only two conductors who

knew Brahms to live to record his music, the other being Felix

Weingartner. Recently, Jerry Dubins wrote, “Weingartner may be the

definitive Brahms interpreter” (Fanfare

36:2). I shared Dubins’s view until I heard

Fiedler’s Academic Festival Overture is a showpiece. It begins decisively, with an underlying rhythm Fiedler returns to following more expansive passages. The orchestral colors are bold and lusty. Gorgeous legato phrasing makes your blood rush as in a Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody. The violins really fly, creating a frisson. Gaudeamus Igitur at the end possesses a pomp and circumstance quality. In the Second Symphony, the introduction to the first movement features rich, shimmering colors. The B portion sounds like a cradle song, with a delicious blend in the strings. Tempo shifts in the development clarify the structure from section to section. The prominent brass have character and bite, while the slow solo horn passage feels like a voice from another world. In the second movement, the strings make a deep, elegiac sound. The winds blend with each other beautifully. Fiedler elicits flexible, sostenuto playing, emphasizing the Non troppo aspect of this Adagio. The third movement is truly Grazioso, with elegant contributions by the first chairs. Wonderfully sonorous pizzicato strings add to the total effect. In the last movement, the orchestra’s playing throws off sparks without ever seeming forced. The B section is almost operatic in its emotion. Fiedler’s coda is quick yet noble. This is electrifying music-making.

Fielder’s Brahms Fourth is the most distinctive of these recordings, truly a watershed moment in Brahms interpretation. The conductor shapes the first theme of the opening movement gorgeously. Fiedler evokes a sea tossed world of turbulence, with the occasional sighting of safe harbors. He lingers over transitional passages, creating fineness of tension and sentiment. Despite the variations in tempo, Fiedler always maintains a subtle pulse. As the slow movement begins, Fiedler introduces a quiet domestic scene with a play of light and shadow. Eventually emotion swells up and colors the scene. The A section returns with passionate tones as in Richard Strauss. A feeling of Renaissance music for viol consort is evoked by the great strings-only passage. The third movement truly is Giocoso, a precursor of Holst’s “Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity” and the big tune in the third movement of his friend Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony. Fiedler’s phrasing here always is rounded, never using a sharp attack. Fiedler’s last movement represents a sensible rendering of Brahms’s marking Energico e passionato—not frenetic. Transitions possess a Vermeer like stillness, while the brass choirs are like the rolling clouds in a Constable landscape. The symphony ends with high tragedy: nihilistic, as Karajan called it. Nevertheless, this is a Brahms Fourth that is alive in every bar.

The concerto is by far the least interesting of these recordings. Obert-Thorn relates how pianist Elly Ney (who, incidentally, was a famously enthusiastic supporter of the Nazis) went back into the studio a few months after Fiedler’s death and rerecorded most of the first and last movements, with an unnamed conductor ghosting for Fiedler. I must confess that when I first heard this recording on Biddulph some years ago, I was unaware of the ghost. On this new remastering, however, one can hear that the ghost’s contribution is superficial, lacking Fiedler’s concentration and precision. Ney gives the first movement a big boned, conventional interpretation, lacking tension and littered with mistakes; Ney did not practice much. In the next movement, the bar to bar musical communication—with Fiedler—is much more palpable. The orchestra’s fugato episode has nobility, and the rest of the movement following it is passionate. The slow movement features stately and dignified cello playing by Tibor de Machula. Ney has some fine moments, while Fiedler doesn’t challenge her tempos or expression. At the start of the last movement, Fiedler offers Ney wise support, but when the ghost takes over things become fairly perfunctory. Throughout the CDs, Obert-Thorn provides honest and listenable transfers. If you are looking for stereo recordings of these works, I would recommend Antal Doráti for the symphonies, Claudio Arrau with Bernard Haitink in the concerto, and for the overture, Leopold Stokowski. Fiedler’s purely orchestral studio recordings are a great moment in the history of Brahms interpretation. No matter which performers of Brahms you prefer, I doubt you will hear the composer the same way after listening to Fiedler. He clearly was a remarkable musician.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:5 (May/June 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.