This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

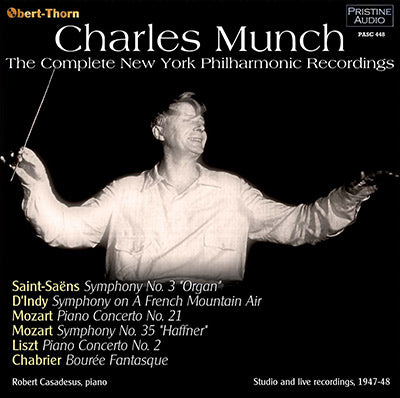

Complete Charles Munch with the New York Philharmonic

"Munch’s

way with the score is viscerally exiting, and the orchestra’s response

is fantastic. No wonder the audiences and critics went wild" - Fanfare

The recordings in this collection document a brief but memorable collaboration in the histories of Charles Munch and the New York Philharmonic. Munch had been scheduled to make his American début in December, 1939, but war intervened. When he finally arrived precisely seven years later, it was to begin a three month tour throughout the United States and Canada. Although the first stop was, propitiously, Boston, New York was next on the itinerary.

Munch began a two-week stay with the Philharmonic on January 23, 1947. The response from audience, critics and orchestra alike was ecstatic. “The instant that Charles Muench [as his name was then spelled] raised his baton as guest conductor,” critic Olin Downes wrote, “[. . .] it was evident that we had with us a superb musician and orchestra leader to boot.” The backstage reception at the end of his stay was reported to have rivaled that given to Arturo Toscanini at his departure from the ensemble. Coincidentally, the next day, the Philharmonic’s music director Artur Rodzinski announced his resignation due to unrelated grievances. Immediately, speculation centered on Munch as a potential replacement.

Munch appeared with the orchestra again late in 1947, and this time Columbia Records, which had the Philharmonic under contract, took advantage of his presence to make the conductor’s first American recording, the Saint-Saëns “Organ” Symphony. This was the first recording of the work since Piero Coppola’s pioneering 1930 set, and would remain unchallenged in the catalog for several more years.

At the end of the following year, Munch would make two more recordings with the orchestra of works by D’Indy and Mozart, both with fellow Frenchman pianist Robert Casadesus. But there would be no more collaborations on disc with the Philharmonic, for by that time Munch had already signed with the Boston Symphony to become their music director starting with the 1949-50 season. He would not appear again as guest conductor with the Philharmonic until 1965, after his Boston tenure ended, and he conducted them for the last time in 1967.

To fill out this modest discography, I have added portions of the Sunday afternoon CBS Philharmonic broadcast from the day before the D’Indy and Mozart recording session. It is complete except for a live performance of the D’Indy, and the program and commentary have been edited so as to present it as a self-contained “mini-concert”. (The commentator is writer, composer and broadcaster Deems Taylor, best remembered today for his similar hosting duties in the Walt Disney film, Fantasia.)

Each work is significant in Munch’s repertoire. He never made a commercial recording of any Mozart symphony, usually being relegated on disc to concerto accompaniments. His only other recording of Liszt was a wartime set of the First Concerto; and despite his many discs of French repertoire, he never recorded any Chabrier at all.

The transfers of the commercial recordings were made from American Columbia grey-label “six-eyes” LP pressings, which themselves were dubbed from 33 1/3 rpm lacquer masters, edited together from four-minute long takes in those last days before the introduction of magnetic tape. The broadcast came from a tape dubbing from original acetate discs.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

SAINT-SAËNS Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 78, “Organ”

Recorded 10 November 1947 in Carnegie Hall, New York

Matrix nos.: XCO-39319/26

First issued on Columbia M-747 (78 rpm) and ML-4120 (LP) -

D’INDY Symphony on a French Mountain Air, Op. 25

Recorded 20 December 1948 in the Columbia 30th Street Studios, New York

Matrix nos.: XCO-39925/30

First issued on Columbia M-911 (78 rpm) and ML-4298 (LP) -

MOZART Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major, K.467

Recorded 20 December 1948 in the Columbia 30th Street Studios, New York

Matrix nos.: XCO-39931/38

First issued on Columbia M-866 (78 rpm) and ML-2067 (LP)

From the CBS broadcast of 19 December 1948 at Carnegie Hall: -

MOZART Symphony No. 35 in D major, K.385, “Haffner”

-

LISZT Piano Concerto No. 2 in A major, S.125

-

CHABRIER (orch. Mottl) Bourée Fantasque

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York ∙ Charles Munch

Robert Casadesus (piano) (D’Indy, Mozart K. 467, Liszt)

Édouard Nies-Berger (organ) (Saint-Saëns)

Walter Hendl and Arthur Schuller (piano) (Saint-Saëns)

Fanfare Review

The sound of this 1947 NYPO Saint-Saëns Symphony is astonishingly good, almost beyond belief, and the performance is absolutely terrific

These recordings were made between 1947 and 1948 during the New York Philharmonic’s fleeting flirtation with Charles Munch. Producer Mark Obert-Thorn’s program note lays out the brief history. On his arrival in the U.S. in 1946, Munch found himself in Boston. But in January 1947 he was engaged for a two-week guest appearance in New York. Audiences and critics alike were ecstatic. The day after his final concert, the New York Philharmonic’s permanent music director, Artur Rodzinski, resigned his post in a snit over a dispute with management that had nothing to do with Munch. Munch’s name was floated as a potential replacement, but in the political turmoil created by Rodzinski’s abrupt departure, the orchestra’s board members didn’t act fast enough; and while they dithered, Munch was snapped up by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

The temporary vacancy in New York was filled by Leopold Stokowski and Dimitri Mitropoulos sharing the podium, until Mitropoulos assumed the post on a full-time basis in 1949. Meanwhile, however, Munch was invited back to New York as a guest conductor late in 1947, and again late in 1948, and it was during these two engagements, with the orchestra under contract to Columbia Records, that these performances were recorded.

The first of them, the Saint-Saëns “Organ” Symphony, recorded live in Carnegie Hall on November 10, 1947, is of special historical interest because it’s the first commercial recording of the work since Piero Coppola’s pioneering 1930 effort with the Grand Orchestre Symphonique du Gramophone, and the first by an American orchestra. A dozen years after this Munch Saint-Saëns with the New York Philharmonic, the conductor would of course go on to make one of the all-time classic recordings of the work, for RCA in 1959 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Berj Zamkochian at the organ. Munch had a special flair for the French repertoire, which comes to the fore again in the later recorded d’Indy and Chabrier numbers in this collection.

The next two items on these discs—Vincent d’Indy’s Symphony on a French Mountain Air and Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21—are studio recordings, both made on December 20, 1948, in New York’s Columbia 30th Street Studios. The pianist on deck was Robert Casadesus, who subsequently went on to record a series of Mozart’s later piano concertos with George Szell and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, and the d’Indy with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Munch would also record the d’Indy again 10 years later, but this time with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Nicole Henriot-Schweitzer at the piano. To the best of my knowledge, Munch’s Mozart discography is pretty slim. He did record a Piano Concerto No. 20 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Clara Haskil in 1956, the “Linz” and “Prague” Symphonies with the BSO in 1959 and 1960, and most famously, the Clarinet Concerto with the BSO and Benny Goodman in 1956.

The “Haffner” Symphony, Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 with Casadesus, and the orchestral arrangement of Chabrier’s Bourrée fantasque by Felix Mottl are taken from a live CBS Philharmonic radio broadcast of a matinee concert on Sunday, December 19, 1948, the day before the Mozart and d’Indy studio recording was made. Also included on that concert was a performance of the d’Indy, but only the studio performance of the next day is included here.

Obert-Thorn provides the technical recording details as follows: “The transfers of the commercial recordings were made from American Columbia grey-label ‘six-eyes’ LP pressings, which themselves were dubbed from 33-1/3 rpm lacquer masters, edited together from four-minute long takes in those last days before the introduction of magnetic tape. The broadcast came from a tape dubbing from original acetate discs.”

This is where I’d be expected to say something like “if you’re a Munch fan, you will surely want to add this to your collection, but…” the “but” being that Munch revisited the Saint-Saëns and d’Indy works a decade later in Boston for RCA in more up-to-date sound. That’s what I’d be expected to say, anyway, but frankly, the sound of this 1947 NYPO Saint-Saëns Symphony is astonishingly good, almost beyond belief, really, in this Obert-Thorn transfer; and the performance is absolutely terrific. Yes, the timpani are a bit muffled in the first half of the second movement, and the organ’s big entrance at the beginning of the finale may not raise the dead, but Munch’s way with the score is viscerally exiting, and the orchestra’s response is fantastic. No wonder the audiences and critics went wild. One can’t help but wonder what might have been had New York offered Munch the directorship before Boston did.

I should probably mention at this point that the December 19, 1948 broadcast concert has been previously released in full by Lys—meaning it includes the live concert d’Indy omitted from this set in favor of the following day’s studio recording. Also, I find myself questioning the claim that these are Munch’s complete New York Philharmonic recordings. I’m looking at a detailed and comprehensive Munch discography at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles Munch discography, and from January 2, 1949, there’s a recorded broadcast of a concert with Munch conducting the NYPO in Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé Suite No. 2, and featuring violinist Ginette Neveu performing Chausson’s Poème and Ravel’s Tzigane. Those performances are available on a two-disc Music & Arts set, 837, containing other non-Munch, non-NYPO material.

You’d think that the d’Indy Symphony on a French Mountain Air, having been recorded a year later and under studio conditions would have even better sound than the Saint-Saëns, but it doesn’t. In fact, it’s rather poor, with a frequent low rumbling and some fairly pronounced overload distortion in loud passages. I haven’t heard the day-before in-concert version on Lys, but I wonder if using it instead of this studio recording might have been preferable.

The Mozart Concerto with Casadesus not only exceeded my expectations, it’s even better, I think, than the pianist’s later remake with Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. There’s a buoyancy to Munch’s upbeat tempo and rhythmic alertness—listen to how fast Munch takes the finale—that carry Casadesus right along in a reading that sounds more natural, more spontaneous, and happier than does his rather straitlaced performance under Szell. Casadesus provides his own cadenzas, and the sound is terrific.

The Mozart Symphony, Liszt Concerto, and Chabrier arrangement are prefaced on disc two of this set by a spoken introduction to the radio broadcast by Deems Taylor. Munch takes the “Haffner” Symphony at a good clip, but his reading sounds a bit formally stiff. The conductor doesn’t sound quite as comfortable or as unbuttoned as he is in the concerto with Casadesus. The New York Philharmonic, however, gives Munch playing of unparalleled discipline, and for a radio broadcast, the sound is really very good.

More talk from radio show host Taylor follows applause at the end of the symphony and introduces the Liszt Concerto. Casadesus was not the sort of flashy virtuoso pianist I would ordinarily associate with Liszt, but his performance of the composer’s Second Piano Concerto at that December 19, 1948 matinee concert was astonishingly—frighteningly, really—diabolical. Liszt’s orchestration occasionally overwhelms the recorded sound; the timpani, especially, can take on the sound of muffled, distorted war drums in the distance. But Casadesus’s piano comes through with pristine clarity. There’s more chatter from Taylor at the end of the Liszt over loud applause and in preface to the final work on that day’s program, a lollipops orchestral arrangement of Chabrier’s Bourrée fantasque.

This is a collection not just for the Munch fan. In many ways, it illustrates how conscious of and conscientious towards appropriate style a number of great conductors and orchestras were back in the day before the HIP movement gained traction. Munch’s tempos, French refinements, and musical instincts bring most of these works to life in ways that many of today’s podium maestros have reason to envy.

Jerry Dubins

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:3 (Jan/Feb 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.