This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

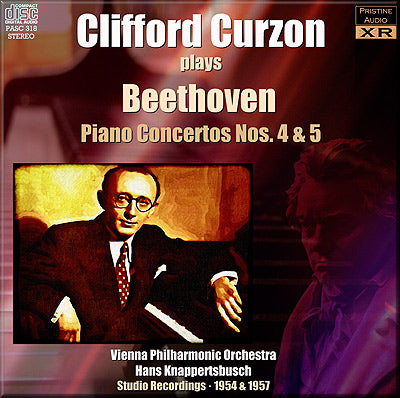

- Cover Art

Clifford Curzon is "the ideal pianist for the Fourth"

Two excellent Decca recordings given new life by Pristine's XR remastering

These two recordings straddle Decca's move in the mid-50s from

mono to stereo - the mono Fourth Concerto here is presented in Ambient Stereo,

retaining a central mono sound but allowing hall ambience some realistic stereo

spread. Both recordings were rather constrained and a little boxy in sound,

something that XR remastering has largely cured. Viennese orchestral pitch was

notably high in the Fifth Concerto, something I've confirmed with electrical

hum analysis - both original pitches have been accurately and precisely

restored.

Andrew Rose

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 4 in G, Op. 58

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Cyril Windebank

Recorded 4-5 April, 1954

Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

Transfer from Decca ECS 752

Presented in Ambient Stereo

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Cyril Windebank

Recorded 4-5 April, 1954

Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

Transfer from Decca ECS 752

Presented in Ambient Stereo

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Op. 73, "Emperor"

Mono Producer: John Culshaw

Stereo Producer: Erik Smith

Mono Engineer: Gordon Parry

Stereo Engineer: James Brown

Recorded 10-15 June, 1957

Sofiensaal, Vienna

Transfer from Decca SXL 2002

Presented in Stereo

Clifford Curzon piano

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Hans Knappertsbusch conductor

Mono Producer: John Culshaw

Stereo Producer: Erik Smith

Mono Engineer: Gordon Parry

Stereo Engineer: James Brown

Recorded 10-15 June, 1957

Sofiensaal, Vienna

Transfer from Decca SXL 2002

Presented in Stereo

Clifford Curzon piano

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Hans Knappertsbusch conductor

Fanfare Review

This classic combination of pianist and conductor belongs in everyone’s collection

These 1954 (No. 4) and 1957 (No. 5) monaural studio recordings have been remastered into stereo by the master-of-remastering, Andrew Rose, under the renowned Pristine label. The featured artists, Clifford Curzon and Hans Knappertsbusch, are masterly performers from the past. I have been an admirer of Curzon’s playing, but a very neglectful admirer because I own none of his very few recordings. I have never liked what little I’ve heard of Knappertsbusch’s conducting except for that on an old vinyl disc set of Die Meistersinger— a remnant of my previous life as a Wagnerphile. Andrew Rose has sparked in me a reassessment, not of Wagner but of Knappertsbusch, and a reappreciation of Curzon.

Curzon’s phrase shaping and passagework are noteworthy, and Knappertsbusch’s command of the orchestra enabling detail to be heard without overwhelming the piano is especially appreciated. The Vienna Philharmonic’s violin sections, however, are, while adequate, not of the high quality encountered in today’s best orchestras.

Curzon’s quiet solo entry to begin the first movement of the Fourth Concerto is truly poetic, presaging the character of the entire movement. Knappertsbusch is suitably responsive, allowing the fine orchestral detail to be heard in lyrical response. The orchestra enters strongly to begin the unusual second movement, and Curzon responds in quiet reverence. This pattern changes, as the orchestra diminishes its prominence, and the piano takes command—in the style of responsive reading. Curzon and Knappertsbusch trade roles of dominance and subordinance as the movement progresses. Curzon is enthralling in the impressionistic solo passages from bar 56 through bar 63. This is as good as the classic treatment found in the Artur Schnabel/Malcolm Sargent recording of the 1930s. The final movement is exuberant and well articulated. Curzon’s legato is especially noteworthy.

As good as the Fourth Concerto is, the “Emperor” is even better. Curzon’s bold entry at the start of the first movement employs rubato very carefully as a foreshadowing of the movement’s majesty to come. Knappertsbusch controls the orchestra superbly to reveal the movement’s great detail. Revelation of the “Emperor”’s dominance among concertos is shared equally here by both pianist and conductor. Knappertsbusch’s reverential opening of the second movement is complemented by Curzon’s poetic entry. This magnificent combination pervades the movement. Curzon is unmatched here, except possibly by Artur Schnabel. The final movement is worthy of the “Emperor”’s crown as Curzon and Knappertsbusch in concinnity tame its tempestuous exuberance to conclude a grand musical experience.

This classic combination of pianist and conductor, recorded almost 60 years ago, belongs in everyone’s collection. Courtesy Andrew Rose and associates, it is a sonic marvel for its age (although there is occasional orchestral blurring); courtesy Curzon and Knappertsbusch, it is a marvelous musical experience.

Burton Rothleder

Burton Rothleder

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:6 (July/Aug 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.