This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

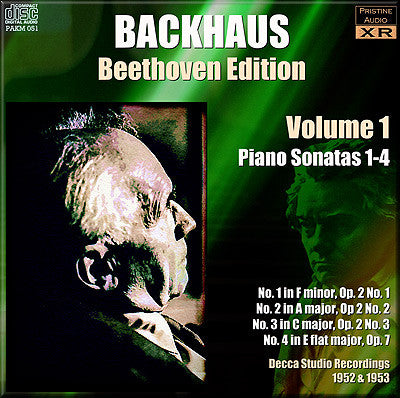

Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle begins here

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

Wilhelm Backhaus's first Beethoven Piano Sonata cycle, recorded between 1950 and 1953, was one of the first for the Long Playing record, and may well have been the first of several contemporary accounts to reach completion. Backhaus was already considered, as the review above points out, a "veteran" pianist, yet later that same decade he started the sonatas all over again, once more for Decca, this time in stereo, a cycle which he almost completed prior to his death in 1969, leaving only the Hammerklavier not re-recorded.

The existence of the stereo cycle has led to this mono cycle, which a number of listeners consider the better of the two, to be neglected by Decca - outside of Japan and a very limited Italian issue, it has never been reissued by the company. Sonically there's no doubt that the later recordings improved considerably over these early 50s mono versions, but there's much that can now be achieved in improving considerably the sound quality of these recordings, as well as correcting the "slight mechanical erraticisms of pitch and surface-hum" referred to in the review above.

In making these historic recordings, from one of the greatest of Beethoven interpreters, available again in fine-sounding 32-bit XR remasters, collectors can at last and with ease determine their own preferences with regard to the Backhaus discography.

Finally a note about pitch: The recordings so far analysed suggest some wayward tape speeds, resulting in pianos pitched variously at between A=432 and A=444, as well as some notable pitch changes, both sudden and sliding, during movements within recordings. One later recording in the series (to be released as part of Volume Three) includes what I take to be a "sticky edit", causing the pitch to lurch alarmingly (at one point it drops more than a semitone) over the course of several notes before steadying itself. Previously just about unfixable, these problems have all been resolved and the pitch of each recording standardised to A=440.

Andrew Rose

Second volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

Gramophone's reviewer in 1951 notes some blasting on louder passages on his LP copy, and likewise I had to deal with shortcomings of the recording which I firmly ascribe to the early tape system in use - which was much improved by November 1953 for the later three recordings in this volume. Whether or not the reviewer was hearing disc blasting, there was often a tendency towards a mushy kind of tape hiss to surround the upper frequencies of louder notes and chords, and I've spent a lot of time removing or taming these.

Elsewhere, pitch has once again been susprisingly variable, both in terms of overall tuning, and in clear issues with both tape machines and editing, all of which can now be remedied. Sound quality was generally good - my aim here, which I feel has been achieved, has been to clarify the piano tone whilst reducing background noise and hiss.

Andrew Rose

Third volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

As with other releases in this series I've taken great care to bring

consistency to the tuning of Backhaus's piano where previously it was

absent - the average pitches for each of these four sonatas as presented

by Decca were A4 = 433.9, 442.5, 432.7 and 438.7 hertz respectively.

Furthermore the 12th started low, before drifting gradually upwards,

whilst the opposite effect was to be heard in the 13th. Owners of the

Japanese Decca (London) CD reissue of the 13th will also be familiar

with a 'sticky edit' pitch lurch of more than a tone in the finale, not

present here, as well as several completely missing notes in the middle

of first movement!

Tonally I've continued to accept slightly

higher than usual levels of tape hiss in order to bring out the full

tone of Backhaus's piano, something which was considerably muted in the

Decca incarnation. Once again it was no surprise to discover that the

later recordings were of somewhat better audio quality than the earlier

ones.

Andrew Rose

Fourth volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

Andrew Rose

Fifth volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

"The two little Sonatas, for many of us our first steps in Beethoven, are given with charm and simplicity. The recording of all these is good."

A.R. The Gramophone, October 1953 (Reviewing LXT2780, excerpt concerning Sonatas Nos. 19 & 20)

"In the C major, Backhaus is frequently allowed to "play through the piano" (the two sides were listened to consecutively at exactly the same level of dynamics, on the same set, and in the same room). Colour-range is good, but the atmosphere is studio-like, and the total effect resembles Beethoven's instrument much nearer than Backhaus's. The second movement opened with warmer tone, but I was out of sympathy with the playing here. There is one triumph for Backhaus on this side—his magnificent handling of the Rondo with its almost magical (certainly fairystory) quality of mysteriousness. From this the pianist builds up a castle-like structure. The recording engineers were kind (at last) to his opening but allowed unlikeable thinness to creep in as he warmed up his interpretation."

H.F. The Gramophone, June 1951 (Reviewing LXT2532, excerpt concerning Sonata No. 21, "Waldstein")

Of the two contemporary reviews quoted here, the second, of the Waldstein, perhaps puts its finger on a significant point regarding a good number of the mono Beethoven sonata recordings made by Backhaus for Decca between 1950 and 1954 and represented in this series - and their often less-than-glowing reception at the time . It also suggests to me that their remakes later in the same decade and through the 1960s were for reasons more varied than simply the advent of stereo.

Put simply, I believe that the Decca production team in Geneva were struggling badly with new technology, particularly in the earlier of the recordings, and all too frequently either made basic errors or were let down by the new-fangled tape equipment at their disposal.

Never in this era have I seen pitch change as much as is heard in the original recording of Sonata No. 19. It begins more or less in tune, though with some wavering through the first of the two movements. But the second, across just three minutes, sinks an entire semitone, leaving the piano tuned to 422Hz rather than 440Hz. It's astonishing that a player as sensitive to pitch as Backhaus could have approved this.

The acoustic was often desperately lacking in sympathy, something I've aimed to ameliorate. But I've also had to tackle peak distortion, wayward electrical tones, high background hiss, and poor overall tone. I can only wonder at how much more favourable some of the reviews might have been had the performances been properly recorded in the first place.

Critical assessment of performances can too often be badly skewed by inadequate recordings, where crucial aspects of those performances are lost. Backhaus deserved better - I hope this series rectifies this.

Andrew Rose

Sixth volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

"While Backhaus's understanding of Beethoven is not, at this time of day, in any dispute, there is room to question whether these particular performances succeed in conveying it to the listener. They are dominated by a savage attack, and a refusal to play below an mp-mf degree of volume; a refusal that may be the result of many years' experience of recording under less satisfactory technical conditions than to-day's—which are here not on their very best behaviour, but are nevertheless good, and of course greatly superior to those that may be in Backhaus's mind .. The Appassionata stands up to the strain fairly well ; and is, indeed, particularly in the last movement, an impressive display of technical powers of the most advanced kind."

M.M. The Gramophone, September 1952 (Reviewing LXT2715, excerpt concerning Sonata No. 23)

"The classical, precise, authoritative Backhaus is presented here with uncommonly lifelike quality. He has his minor erraticisms, but they are no more than a part of the person who is presenting a great master for our full attention. Backhaus's own intense conviction of the composer's mastery fully overcomes any doubts one might have about the music. In truth, not one of these three sonatas is of great magnitude—that in G major (op. 79), Beethoven himself entitled " sonate facile ou sonatine."... I like the brittle, guitarry effect Backhaus creates for the opening movement of Op. 79: it has a kind of peasant air about it. The andante is taken well under walking pace, and I could bear the vivace finale more headlong. From this disc I had slight trouble with blast, which remained even if one turned the dynamics down. Backhaus's percussive style need not lead to this fault."

H.F. The Gramophone, October 1951 (Reviewing LXT2603, excerpt concerning Sonata No. 25)

I have pointed out in previous technical notes that it has increasingly become my opinion that this series of Beethoven sonata recordings is one neglected - and, in its day, often disparaged - not primarily as a result of the playing by Backhaus of these works, but the by the raw deal he was served up by Decca's inadequate recordings.

In this volume pitch is, for the most part, not the issue seen previously, the exception being the first movement of the Appassionata, which dips alarmingly to begin with before proceeding to waver and jump about throughout the movement, most probably the result of editing together various takes as much as poor general tape speed stability. This has, for the first time, been corrected.

I would have to take issue with The Gramophone reviewer's suggestion that Backhaus refuses to play below mp-mf throughout the work - but can well imagine that impression being given by poor reproduction of his playing. Much of this is now happily alleviated here, and these interpretations can be more clearly judged within the excellent sonata cycle they so clearly combine to produce.

Andrew Rose

Seventh volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

Listening to these three recordings it's not difficult to distinguish the sonata recorded in 1954 from those recorded two years previously. The overall tone of Sonata 27 has a richer quality than I've been able to bring out in Sonatas 28 and 29, and in its original review in The Gramophone (not quoted here) the reviewer ends with an observation that: "The whole of this disc is very well recorded", something of a contrast to the criticism directed at the Hammerklavier recording.

The latter sounds, to modern ears, especially flat and boxy, with a very limited lower extension which appears almost to hollow out the sound of the piano. The result is indeed a recording which suggested a much poorer performance than Backhaus actually gives as it minimises the impact of both the dynamic range of his playing and the subtleties therein.

In all three sonatas in this volume I've been able to enact a dramatic transformation in the sound of the piano, despite almost constantly having to fight against multiple shortcomings in the original recordings, something that has been a constant throughout this series. Pitchwise, apart from a sag during the first movement of Sonata 28, these were generally fine. But in the recovery of piano tone I've had to lift a lot of tape "shash" into the realms of audibility - and then try to suppress this whilst retaining the piano. By and large this has been a successful mission, but at times one may still be reminded of the vintage of these recordings.

Andrew Rose

Eighth and final volume in Backhaus's magnificent first Beethoven Sonata cycle

Long only available on rare imports, and in new 32-bit XR remasters - this is unmissable

Sonata No. 30 was among the earliest recorded in this series and among the few to be released on 78s alongside an LP. Nevertheless it's almost on a par with the two 1953 recordings with regard to technical quality. All three were again less than ideal, with various flaws familiar to this cycle, yet beyond a tendency to upper-frequency fuzziness and some pre- and post-echo they were generally at the higher end of the quality scale when looked at in that context. Perhaps the fact of a 78rpm issue of the first of these three works should serve as a reminder of the somewhat primitive technical origins of Backhaus's first complete cycle - by the time he returned to Beethoven sonatas in the Decca studios a few short years later, recording technology had advanced considerably.

Andrew Rose

"A magnificent achievement", played with "an astonishingly youthful vigour" - Gramophone

Backhaus's stereo Diabelli Variations and Piano Concerto No. 1 in new 32-bit Pristine XR remasters

Tonally the Piano Concerto recording was good in this stereo version (possibly offering a different tone to the mono release reviewed above), if somewhat hissy, and this restoration has concentrated mainly on reducing the latter as well as correcting some quite significant pitch anomalies at edit points throughout the recording. These caused jumps in the pitch of the recording were edits from different takes had been made or up to a quarter-semitone at a time, helping make some edits sound particularly clunky.

The recording was also rather sharp, more so than the Diabelli Variations, which managed a far more even and consistent A=445Hz. Here my efforts were concentrated on lifting the veil on a somewhat thin and boxy-sounding instrument, coupled with the removal or suppression of a large number of extraneous clicking noises which appeared to emanate from the keyboard itself.

Andrew Rose

"A fine performance matched by a first-class recording" - Gramophone

Backhaus's classic Concerto recordings have been completely transformed in these new remasters

Both of these recordings, whilst fundamentally sound, have benefited enormously from a thorough restoration and XR remastering - given the recording dates, right at the beginning of the adoption of tape mastering and LP distribution, the myriad of now-correctable faults was entirely unsurprising. Pitch generally fluctuated between about A=335Hz and A=440Hz, and these variations have been evened out to concert pitch - but the coda of Concerto No. 2 came in at A=432Hz - a significant drop suggesting a section edited in from a very different recording.

The tonal difficulties suggested in contemporary reviews sound even more pronounced today, I would suggest, given our far improved listening equipment over a reviewer of the early 1950s. Fortunately we now also have the technology and expertise to address these shortcomings. I've also been able to make significant inroads on tape hiss and an assortment of extraneous noises and irrirants. The results here have proved particularly satisfying - a full, clear, clean sound has been discovered both for piano and orchestra to an extent that demands a critical reassessment of both of these recordings. My sense is that, as has happened regularly before, the listener will now find significantly more to enjoy here than in any previous release.

Andrew Rose

"Backhaus and Clemens Krauss give us a fine performance" - Gramophone

Backhaus's classic Concerto recordings have been completely transformed in these new remasters

As with previous recordings in this series, I have been able to tackle not just the issues of background hiss and tonal balance, but also pitch. The Concerto No. 4 showed a gradual slide upwards through the second movement from a low start, whilst the finale drooped off at the very end. The Emperor, whilst benefiting from significantly finer sound quality, proved to be considerably erratic, pitch-wise, suggesting multiple and quite frequent edits between takes from different days or machines causing regular jumps up and down. Both concertos have been leveled out to concert pitch.

I was able to release superb sound quality in both, and though the strings in the earlier recording still show a tendency towards shrillness, they are much improved over the original harsh sound here, without any imparment in the clarity of the piano tone which might have resulted from a straightforward reduction in treble. No such problems with the Emperor, where an already fine sound has been further rounded out, with greater extension in both treble and bass and a more generous overall feel from an excellent recording.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 2 No. 1

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2902

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 2 No. 2

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2920

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 3 in C major, Op. 2 No. 3

Recorded May 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2747

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 4 in E flat major, Op. 7

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2809

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 5 in C minor, Op. 10 No. 1

Recorded March 1951

Issued as Decca LXT 2603

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 6 in F major, Op. 10 No. 2

Recorded March 1951

Issued as Decca LXT 2603

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 7 in D major, Op. 10, No. 3

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2809

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13, "Pathétique"

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2903

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 9 in E major, Op. 14, No. 1

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2903

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 10 in G major, Op. 14, No. 2

Recorded April 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2931

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 11 in B flat major, Op. 22

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2920

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 12 in A flat major, Op. 26 "March Funébre"

Recorded June 1950

Issued as Decca LXT 2532

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 13 in E flat major, Op. 27, No. 1 "Quasi una fantasia"

Recorded November 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2780

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 14 in C sharp minor, Op. 27 No. 2 "Moonlight"

Recorded October 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2780

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 15 in D major, Op. 28 "Pastorale"

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2903

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 16 in G major, Op. 31 No. 1

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2950

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31 No. 2 "The Tempest"

Recorded May 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2747

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 18 in E flat major, Op. 31, No. 3 "The Hunt"

Recorded May 1954

Issued as Decca LXT 2950

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 19 in G minor, Op. 49, No. 1

Recorded November 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2780

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 20 in G major, Op. 49, No. 2

Recorded January 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2780

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 21 in C major, Op. 53 "Waldstein"

Recorded July 1950

Issued as Decca LXT 2532

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 22 in F major, Op. 54

Recorded April 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2931

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57 "Appassionata"

Recorded April 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2715

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 24 in F sharp major, Op. 78 "A Thérèse"

Recorded April 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2931

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 25 in G major, Op. 79

Recorded March 1951

Issued as Decca LXT 2603

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 26 in E flat major, Op. 81a "Les Adieux"

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2902

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90

Recorded January 1954

Issued as Decca LXT 2902

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 28 in A major, Op. 101

Recorded April 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2715

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 29 in B flat major, Op. 106

"Große Sonate für das Hammerklavier"

Recorded April 1952

Issued as Decca LXT 2777

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109

Recorded July 1950

Issued as Decca LXT 2535 and on 78s as AX361-62

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 31 in A flat major, Op. 110

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2939

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111

Recorded November 1953

Issued as Decca LXT 2939

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recording producer: Victor Olof

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt conductor

Recorded 16-22 April 1958

First issued as Decca BR 3001

Producer Erik Smith

Engineer Alan Abel

Recorded at Sofiensaal, Vienna

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Recorded 14-20 October 1954

First issued as Decca LXT 5016

Producer Victor Olof

Engineer Roy Wallace

Recorded at Victoria Hall, Geneva

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, February 2012

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Wilhelm Backhaus

Total duration: 76:51

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 19

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Clemens Krauss conductor

Recorded 25-26 May 1952

First issued as Decca LX 3084

Producer Victor Olof

Engineer Cyril Windebank

Recorded at Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Karl Böhm conductor

Recorded 23 September 1950

First issued as Decca LXT 2553

Producer Victor Olof

Engineer Cyril Windebank

Recorded at Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, February-March 2012

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Wilhelm Backhaus

Total duration: 61:45

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 4 in G, Op. 58

Recorded May 1951

First issued as Decca LP LXT 2629 and 78s KX28542-45

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Op. 73, "Emperor"

Recorded May 1953

First issued as Decca LXT 2839

Producer Victor Olof

Engineer Cyril Windebank

Recorded at Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

Wilhelm Backhaus piano

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Clemens Krauss conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, March-April 2012

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Wilhelm Backhaus

Total duration: 70:11

Fanfare Review

A truly great performance that anyone who loves the work should hear

REVIEW OF PIANO CONCERTOS 4 & 5

Pristine Audio has recently issued an all-Beethoven Wilhelm Backhaus Edition containing his first cycle of the sonatas, recorded for Decca in the 1950s, the Diabelli Variations, and the five piano concertos with Krauss, Böhm, and Schmidt-Isserstedt conducting. These recordings from 1951 (No. 4) and 1953 (No. 5) are Pristine’s Volume 11 in the series. Backhaus is inconsistent in the sonatas. He plays some of them with authority and real engagement, but others sound perfunctory, not fully interpreted. This is also the case with the two concertos. While the Fifth represents his playing at its most controlled and communicative, he doesn’t seem to identify as much with the less monumental Fourth.

The “Emperor” had quite fine sound to begin with, but Andrew Rose has corrected pitch problems along with issues of background hiss and tonal balance in both concertos. The result is a rich depth of texture in the orchestral sound that’s splendid indeed. No doubt, some of the pleasure comes from the orchestra being the Vienna Philharmonic at a time when the sound of its strings—lush but somehow sweetly personal—and winds was still very distinctive.

Clemens Krauss is a fine Beethoven conductor who offers shapely phrasing and detailed dynamic control. In the livelier sections of the Fourth, he seems to be accompanying a more nuanced performance than Backhaus gives. This is not to say that there aren’t admirable moments. The piano’s opening statement is very beautifully played, and Backhaus is extremely sensitive and precise in the second movement, but his passagework, while accurate, often sounds like he’s on autopilot: driven, metronomic, and without much shape or emotional character. (A good antidote is Schnabel’s joyful, more polished 1933 recording of the Fourth with Malcolm Sargent’s deft accompaniment, but maybe it’s unfair to compare 67- and 51-year-old pianists.)

While tempos in both concertos are fairly standard, the start of the Fourth’s finale sounds miscalculated. It begins deliberately, slower than it should be, and Backhaus’s opening statement sounds restricted and lumpy. A few lines later, he switches gears, creating a true vivace, and the performance improves. I wish that Pristine had identified the rambunctious cadenza—it’s more chromatic and raucous than the usual one by Beethoven—that Backhaus plays in this movement. I wonder whether it could be his own.

The “Emperor” Concerto shows Backhaus at his absolute best in playing that’s steady but not rigid, with rock-solid rhythm and fluent, all-encompassing technique. He has a majestic concept of the first movement, projects strength and good spirits in the third, and gives a direct, heartfelt reading of the slow movement that I find very moving. The recorded sound of the piano is clearer here than in the Fourth. This is not simply a worthy historical recording of the “Emperor,” it’s a truly great performance that anyone who loves the work should hear.

Paul Orgel

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:1 (Sept/Oct 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.