This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

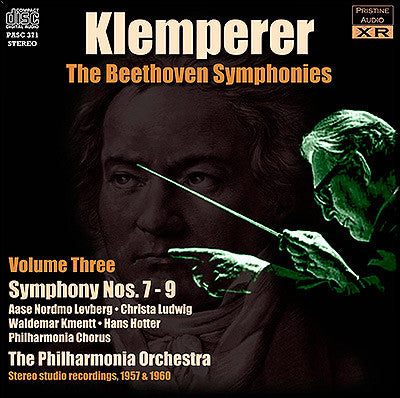

Klemperer's classic Beethoven Symphony Cycle: The final set, Nos 7-9

"The performance is as great as anything one is likely to hear in this world" - The Gramophone

As with the previous releases in this series, I came to the original EMI recordings full of admiration. Consistently well-made and of this highest technical quality for their era, one wonders what benefits might arise from applying XR remastering to them? And then I hear the results - and suddenly those 1950s recordings don't sound so good after all in comparison! This is therefore a project dedicated to extracting the finest sound possible from a very accomplished working base. It is something I believe is as valid for well-known, well-made recordings of the past as it is for the rarer and more troublesome recordings I also work with.

This presents Klemperer at his very best; he can now be heard in unprecedented sound quality, significantly improving on all previous issues.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

- BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 8 in F, Op. 93

-

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 "Choral"

Aase Nordmo Løvberg soprano

Christa Ludwig alto

Waldemar Kmentt tenor

Hans Hotter bass

The Philharmonia Chorus

The Philharmonia Orchestra

Otto Klemperer conductor

Recording dates:

Symphony No. 7 Recorded 25 October, 19 November and 3 December, 1960

Symphony No. 8 Recorded 29-30 October 1957

Symphony No. 9 Recorded 31 October and 21-23 November 1957

Recorded at Kingsway Hall, London

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, November-December 2012

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Otto Klemperer

Total duration: 2hr 22:41

REVIEW Beethoven Symphony No. 9

Here is the much anticipated Klemperer Ninth. So many

readers will have heard him conduct this in the concert hall or on the

radio, or will at any rate know his way with Beethoven from other

records, that it seems hardly necessary to describe the result in much

detail - it is so obviously going to be a great Beethoven

interpretation. And so, indeed, it is, with the Columbia technical staff

all out, too, to make the result a success.

But although we may

know conductor and orchestra, there are two less predictable

participants in this perfonnance, the soloists and the Philharmonia

Chorus (who here make their debut on records). Soloists, bless their

hearts (or, curse them, according to your mood) are seldom predictable.

The best known of this quartet is Hans Hotter, a fine singer and artist

indeed, but singing his opening recitative in a manner that will

distress many sensitive ears. I f only, one feels, he had concentrated

less on expressing the message of the words and more on singing each

note well in tune, for he pushes some very sharp. Later, when he is

mainly engaged in quartet work, his contribution is excellent.

The

rest are efficient without being remarkable, good enough, at any rate,

not to let things down. The soprano, Aase Nordmo Løvberg, does her

difficult job pretty well, though she tends to force the pace a bit at

the start and her final top B is precise rather than particularly

beautifulnothing like Schwarzkopf's in her performance with Furtwangler.

Christa Ludwig fills her less exacting role well and Waldemar Kmentt is

perfectly adequate, if not remarkable. Whether he has a ringing top B

flat, by the way, one cannot tell, for the chorus covers him when he

should come out with it.

The Philharmonia Chorus is splendid.

Bright tone, incisive attack, boundless energy and all the sustained

power you could wish for- the sopranos' long f f top A at the end of

"der ganzen Welt" section is as thrilling as the subsequent pp chords

from the whole chorus ("muss ein lieber Vater wohnen").

I said

that there was little need to describe Klemperer's interpretation, but

that will not prevent me, like Saki's boring Stephen Thorle, from doing

so! It is a performance which leaves you at the end with the feeling

that every performance of the Ninth should give, that you have been

through a spiritual experience of overwhelming greatness. It is of a

quality that I think no other living conductor could give. And,

different as Klemperer is from Toscanini, the two have certain things in

common. The astonishing attention to detail, the gift ofilluminating

the significance of some detail of orchestration that had escaped one's

attention before: and (which I think Klemperer has in even greater

degree) the achievement of an orchestral balance that gives lucidity of a

kind rarely heard. (Those close-packed imitative entries in the first

movement, bars 427 to 452, have surely never been so clearly heard.)

The

first movement is immensely powerful, but impressed me most of all by

the way Klemperer seizes upon and conveys the essential atmosphere of

every part of it, especially those pp passages of indescribable mystery. The Scherzo,

with the Philharmonia playing the softest sections with astonishing

delicacy, may seem a little steady and cautious in comparison with other

conductors' performances, but it is, in fact, taken at about

Beethoven's metronome mark. (Weingartner's speed was only slightly

faster, but Toscanini's a good deal more so and gave, therefore, an

entirely different feeling to the whole movement.) But Klemperer is a

great respecter of the score and, by the way, is one of the few to

observe the repeat of the second section of this movement. The slow

movement, with a wonderfully rapt meaa voce from the strings, is surely

all that one could wish for and a momentary lapse of ensemble between

violas and woodwind at one point is insignificant beside the satisfying

beauty of all the playing.

This, then is a great experience to hear.

TH, The Gramophone, November 1958 (Review of first LP issue)

The Klemperer 9th in stereo at last -months after its

scheduled release date and a full year after its mono issue. Readers may

speculate as to why those who have been enterprising enough to equip

them.selves into a stereo set-up should have been made to wait so long.

However, I hope they have not given in and bought the mono records, for

the stereo is undoubtedly much superior and it is, in fact, the sort of

recording of this work I have been waiting for.

I put on the

finale straightway (on the principle that we all know E.M.I. can record

an orchestra well enough) and immediately began to think that this

sounded more like a real performance than any record of a choral work I

had ever heard. All the adjectives with which everyone describes stereo

came to mind (I'm sure you know them by now) and the advantage in the

reproduction of this array of soloists, chorus and orchestra is great

indeed.

Direct comparison with the mono sound was difficult

because the two are recorded at very different levels (the stereo lower)

and one had to keep finding an equal volume before any true judgment of

the impact of the chorus or the climaxes was possible. But my main

impression was of the way the stereo sound laid out the forces before me

in a wide arc, with the orchestra more consistently clear against the

chorus than ever before. This spaciousness of the music is the greatest

gain.

Balance is very good, though sometimes different from that

of the mono records. For a year I have been going about saying that

nobody makes the trumpets ring out in the choral part of the 6/8 section

as Klemperer does and how wonderful that is. Well, he doesn't in

stereo! And what he really does one could only discover by hearing a

live performance. Which just shows how much we are at the mercy of the

technicians.

The performance is as great as anything one is

likely to hear in this world. If I criticised any points in my earlier

review, they were of little account in relation to the whole---except,

perhaps, Hotter's singing of his opening passage. (If only Columbia had

D.G.G.'s Fischer-Dieskau).

Readers should notice that this

stereo recording takes four sides and that the Egmont side of the mono

has disappeared. When I consider the quality of what we are given and

compare it with the lack of quality in D.G.G.'s three-sided version, I

can't really regret the Egmont loss. There is absolutely no question of

which to choose between the two, for both immensity of performance and

fineness of recording.

TH, The Gramophone, December 1959 (Review of first stereo LP issue)

MusicWeb International Review

These three recordings are of the highest order and ones I will return to with great pleasure

This is the third volume of the re-mastered “stereo

set” of Klemperer’s Beethoven symphonies. Unlike the budget

EMI Classics set (10 CDs - 4 04275 2) which nevertheless is a great

bargain, these transfers come from pristine LPs. The sound, as I discussed

when reviewing Volume

2 is notable for its superior bass. It sounds like top rate vinyl,

which many older collectors may prefer. Unlike the Mahler

set where EMI have re-mastered and, in the case of the Resurrection

restored the correct length, the EMI re-mastering is from the 1990s.

This is a missed opportunity although not all recent re-masters are

an improvement.

The stereo Seventh has, like the Eroica and the

Fifth been generally, unfavourably compared to the mono recordings

of 1955. The mono Seventh

was last released separately (it is also in the 10 CD set, referred

to above) and my colleague Christopher Howell had reservations. The

first time I heard the 1955 CD in its stereo version (recorded in secret,

along with the mono) in 1988 I was impressed but have since found it

too slow. The first movement compares very unfavourably with Beecham

on EMI and others. Five years later, the first movement is much slower

than the norm but is powerful in its own way. The sound of the orchestra

is excellent. One key point from Klemperer was that like many conductors

of the old school (not Stokowski) was that he divided first and second

violins. This gives an antiphonal effect that is vital in these works.

The slow movement makes a terrific impact, one of the strongest I’ve

heard. This power and conviction continues during the Presto and the

finale although I did find the latter rather lumbering. I recalled Beecham’s

comment about yaks dancing, these yaks seem fairly geriatric.

The sound of the orchestra is excellent and how well the Philharmonia

play. I enjoyed this recording much more than I expected; on its own

terms it’s quite a performance. In addition to the two EMI studio

recordings there are at least four live recordings for those who cannot

get enough of this work under Klemperer; for those enthusiasts may I

direct you to the Naxos Music Library.

The Eighth is a fine “heavy-weight” recording,

made concurrently with the RFH concerts. It certainly shows this work

is not a little symphony. Many of the points I have made referring the

Seventh apply here to a work which Klemperer clearly does not

see as a throwback to the first two symphonies. Whilst there is some

humour here, the performance does not have the joy others, such as Beecham,

have brought to this lovely work. The wind playing, particularly during

the Minuet is delightful and comes over very well in this re-mastering.

All in all, well worth hearing if by no means the only version to have.

When we come to the Ninth we are dealing with one of the

first stereo recordings of the Choral Symphony. It garnered excellent

reviews on its release in 1959 and has always been held in high regard

as has the live recording, made by the same forces on Testamenta

week earlier.

I had not heard this performance for a very long time but was very impressed

right from the start. Klemperer really understands the first movement

in a way few others do, taking us through every part with clear detail

and purpose. The second movement “Scherzo” has been criticized

for its steady tempo but it is very evolving and engaging and credit

must be given to the Philharmonia and the producer Walter Legge. A few

nights ago we listened to the BBC Proms and Valery Petrenko conducting

the work where this movement in particular felt too hard-driven. The

third movement “adagio” is simply superb with everything

in place; the pace just right. Again we hear wonderful wind and string

playing. I thought there was too big a pause between the end of the

“adagio” and the “finale” but when we’re

into the “presto” all is good again and the playing is just

superb. There was some criticism, at the time, of Hans Hotter’s

singing but to my ears the soloists and chorus are first rate. It’s

a tribute to Walter Legge and the engineers as well as to Pristine that

the sound totally belies its 55 years. There is a real sense of the

special occasion, which I find very moving. There were comments, on

its original release, of the virtues of stereo and this is reinforced

in the final part. This is a Ninth that certainly

deserves to be heard and enjoyed.

These three recordings, despite a few reservations, are of the highest

order and ones I will return to with great pleasure, especially the

Choral. Allow me, however, to look elsewhere for more

spirited yaks in the Seventh.

David R Dunsmore