- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

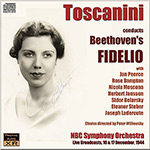

- Cover Art

Toscanini's Fidelio: "daring, fierce, mesmerizing"

And now in fabulous sound quality in these new XR transfers

The broadcasts from which this recording originated were

transmitted a week apart, and the normal mid-programme talk was omitted

in order to fit each act into a one-hour slot. Also omitted was almost

all dialogue, with the opera staged more as a concert piece than a

staged work. An error by soprano

The sound quality of the original recording was adequate, but huge strides forward have been made with the application of 32-bit XR remastering, which has particularly favoured the solo voices here. Although the frequency range tops out at around 10kHz, there is plenty of 'air' and brightness to be heard, albeit with a degree of background hiss at times. I was also able, for the first time, to iron out some quite pronounced pitch variations caused by the original recording equipment drifting up and down in speed.

BEETHOVEN Fidelio

Act 1 transmitted 10th December 1944

Act 2 transmitted 17th December 1944

NBC Studio 8H, New York City

Abscheulicher recorded 14 June 1945

Carnegie Hall, New York City

THE CAST

Jan Peerce (tenor) - Florestano

Nicola Moscona (bass) - Don Fernando

Herbert Janssen (bass) - Don Pizarro

Sidor Belarsky (bass) - Rocco

Eleanor Steber (soprano) - Marcellina

Joseph Laderoute (tenor) - Giacchino

NBC Symphony Orchestra

Chorus Director Peter Wilhousky

Arturo Toscanini conductor

Gramophone Historic Reviews

It is daring, fierce, mesmerizing, to be heard when you're feeling strong of spirit and mind

This isn't music-making for the timid, used to the sanitized, faultless performances on your everyday CD. In its raw, unvarnished way, it is daring, fierce, mesmerizing, to be heard when you're feeling strong of spirit and mind. Toscanini views Fidelio and indeed Leonore No. 3 as stark drama, devoid of sentimentality. The winds leap from the speakers, the brass blare ferociously as the old wizard tells a story of the struggle for freedom in a year when, even in the United States, events far away in Europe must have felt very present. In achieving his end, he demands and mostly receives superhuman efforts from his charges: speeds are nervously fast, rhythms alert, as though the events were happening in the conductor's presence. The wind section is prominent in a way we have since heard from Norrington in Beethoven, indubitably influenced by his predecessor. An occasional untidiness is a price worth paying for such an edge-of-your-seat interpretation. Inevitably the epithet 'hard-driven' has been used about the performance: a visionary conductor, inclined to the dictatorial, demands much from his performers and listeners. No compromises can be made. We won't always want to hear the score done like this; once in a way, it is cleansing and salutary.

According to Harvey Sachs's notes,

Much as one may regret the break for Leonore No. 3, the performance is so electrifying as to silence criticism, but exception has to be taken to the complete absence of dialogue, an essential part of this score. The digital tapes, made from NBC acetates rather than RCA originals, have a little more breadth and reliability than previous transfers to LP. In any case, reservations about sound should deter nobody from sampling this unique experience.

A.B., Gramophone October 1992 (CD reissue, RCA)

REVIEW - LP ISSUE, 1956

Three names - Beethoven, Fidelio, and Toscanini - will be enough for many people and will ask no more. Though they may find the following of interest.

The new Fidelio goes onto four LP sides, as opposed to the six occupied by the previous complete version (reviewed by A.R. in May 1954). "Complete" in the sense that room is found for the Leonora No. 3, without which we should probably feel cheated, though it really has no business herewhile the spoken dialogue, except in the melodrames of the dungeon scene, is cut—giving an effect to anyone who did not know the work that this was an opera of continuous music and not an opera corrtique, as it properly is. Moods are sometimes hereby made to change too rapidly; but one concedes the omissions, in the interest of time—space—money. The interpolated Leonora No. 3 starts the last side and is "scrolled off", so that it may be left out if one wishes. Otherwise the new set is not scrolled at all, as the Vienna performance was, so that it is difficult to pick out individual "numbers", should you wish to.

"New" is also a relative term meaning: publication over here. Actually this Toscanini version, made up from two broadcasts of 12 years ago, is older in time than Furtwangler's, which was made just after the inaugural gala seasion at the new Vienna opera and with the cast and orchestra which had performed it on the opening night. These discs get more on to each side—the first side for instance concludes with the little march, which in the Vienna set is already the second band of the second side, and so on. Also, Toscanini's speeds are appreciably faster in many instances.

Judging between the two is not at all easy; to this opera, unique, one brings a special set of expectations and very varying responses. Music which is alternately sublime and homely, heroic and simple almost to the point of being humdrum, establishes a whole phalanx of contradictory postulates. Is one to insist on heroism and make allowances for the fact that heroes find it hard to wear clogs? Or insist first on the homely, the simple and the natural sounding and make corresponding allowance for "ordinary" characters dealing somewhat unheroically with the sublime? Comparing these two versions is made further difficult by the actual variability of one issue being taken from broadcast tapes.

In a very general way, I would say that those who

already have the grand Furtwängler set, with its somewhat overstrained

Leonora (Martha Mödl) but generally very authentically German sounding

cast, should hesitate before abandoning it in favour of the Toscanini

with a cast not so noticeably better, at least as far as Germanic

authenticity goes.

Furtwängler's handling of the score was masterly and the recording was all very much of a piece: Toscanini's is also masterly, but the recorded quality varies from bright to just faintly distorted. And there are one or two curious smudges in the ensemble, as if the maestro's titanic spontaneity had taken the players off their guard (one such occurs in the menacing orchestral passage which ushers in Florestan's "Welch dunkel . . " in the dungeon scene). Then there are some shifts of level hard to account for: for instance the Prisoners' Chorus seems to have been inserted afterwards like a gusset in a coat (and it will be recalled that it did not make its true theatrical effect in the Vienna set either). After it is over, we jump back to the soloists, like a sudden close-up in a film. Again towards the end of the dungeon scene where in the theatre the mounting excitement comes out at you in a rising tide, the performance here seems, on the contrary, to recede like a camera slowly panning backwards to take in an ever widening (but more distant) scene.

But, and it is an over-riding "but" for a great many people, Toscanini at many points brings an exhilaration to the music which is, quite simply, more purely thrilling than the stately and deeply considered interpretation by Furtwängler. I suggest that you try, one against the other, the trio beginning "Mein Sönnchen..." and play through each version from there to the end of Scene 1. It is not that Toscanini is a fraction brisker; it is that the ideal concept of the music and the performance of it suddenly fuses into one and the same thing. One is no longer conscious of music being made; it is the thing itself, and as the short orchestral postlude lets the pressure down again, one resumes one's ordinary breath rate exactly as one does in a theatre at the fall of a cutain on some scene which has burned you up like oxygen and made you forget everything about yourself and where you are. The scene, which brings the American players and singers to full incandescence, is an example of Toscanini's unique deamon (and unique is the keyword for this opera). For it, and some other like wonders, you may be prepared to jetison the steadier and finally less obtrusive qualities of Furtwängler and the honourable Vienna gala cast.

I should make it clear that the American cast "copes" magnificently - however much one may feel them out of touch with the German character of the dramatic element and the declamatory German style. Both Peerce and Miss Bampton are marvellously on top of "0 namenlose Freude" even at this pace, and for once Toscanini never seems to be overdriving anyone. It must indeed have been a thrilling couple of broadcasts and the issue is one well worth making, possibly of buying, certainly of comparing with the fine six-sided Furtwangler performance from Vienna. That either version makes a quite wonderful impression is of course only to be expected.

P.H.-W., The Gramophone October 1956