This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

“Anthony Vincent Benedictus Collins (3 September 1893 – 11 December 1963) was a British composer and conductor. He scored around 30 films in the US and the UK between 1937 and 1954, and composed the British light music classic Vanity Fair in 1952. His Decca recordings of the seven Sibelius symphonies was only the second cycle by a single conductor and orchestra to appear.

Collins was born in Hastings, East Sussex, in 1893. At the age of seventeen he began to perform as violinist in the Hastings Municipal Orchestra. He then served four years in the army. Beginning in 1920 he studied violin with Achille Rivarde and composition with Gustav Holst at the Royal College of Music.

In 1926, he began his musical career performing as principal viola in the London Symphony Orchestra. For ten years he performed in that orchestra and also in the Royal Opera House Covent Garden Orchestra. He resigned these positions in 1936. For the rest of his career he divided his time between conducting, beginning with opera and moving to orchestra; and composition. His conducting debut was on 20 January 1938, when he led his former colleagues in the London Symphony Orchestra in Elgar's First Symphony, and the following year he founded the London Mozart Orchestra.

He moved to the United States in 1939 to conduct orchestras in Los Angeles and New York City as well as composing film music for RKO Pictures. He was nominated for three Academy Awards for best music and original score in three consecutive years (1940, 1941 and 1942) for Nurse Edith Cavell, Irene and Sunny. He returned to England in 1945, continuing to conduct the major British orchestras and also compose for British film studios. He retired at the end of the 1950s, returning to Los Angeles, where he died at the age of 70 in 1963.

Collins conducted a series of classical recordings, notably of music of Elgar and Sibelius, for Decca Records and EMI. His Decca Kingsway Hall recordings made between 1952 and 1955 of the seven Sibelius symphonies (the second complete cycle with one orchestra and conductor; the first was by Sixten Ehrling and the Stockholm Philharmonic, 1952–1953) and the tone poems were very highly regarded. He recorded with Decca from May 1945 to December 1956.” – Wikipedia

Decca’s LXT series of mono LPs began in June 1950 with LXT 2500, making the first Sibelius symphony probably the 195th twelve-inch LP release for the company. Listening to it today, in this XR-remastered Ambient Stereo release, it’s hard to believe the new technologies of tape and vinyl were not in truly expert hands, and a glance at the name of recording engineer Kenneth Wilkinson immediately confirms this to be the case. This is the Sibelius of magnificent sweeping orchestration, vast soundscapes and beautiful fine details, all immaculately captured some seventy years ago.

The Sibelius was the first of a number of recordings Anthony Collins made with the London Symphony Orchestra; he had already recorded for Decca with both the London Philharmonic and his own London Mozart Orchestra prior to beginning the Sibelius series – his first recording with the former orchestra playing music by Bizet and Falla graced LXT 2510 and was among the very first tranche of British LP releases, issued by Decca in June 1950, whilst his own orchestra had been recorded for 78rpm release in 1945 playing, not surprisingly, music by Mozart.

It is unfortunate that only Collins’ final three recording sessions for Decca were captured in stereo, with his Sibelius series (and much more) recorded entirely in mono. Glancing through the Decca discography it appears the majority of their earliest stereo experiments were conducted with vocal and operatic music, with stereo orchestral recordings not beginning in earnest until late 1956, just before Collins’ retirement. We can, however, with the use of Ambient Stereo, get some idea of the broad sweep of his sound, if not the placing of individual instruments. Even so, it’s a glorious thing to behold in these fabulous symphonies.

ANDREW ROSE

Sibelius's third symphony has been regarded as more classical than his previous works. The scholar Gerald Abraham has argued that the first movement bears strong comparison with the first movements of Haydn's and Mozart's symphonies. Against this background, it seems all the more remarkable that the history of its composition has turned out to be quite complicated.

Influences from Finnish folk music are discernible in the very first chords of the symphony. There were also some programmatic notions behind it. In Paris in January 1906, after a period of lively celebrations, Sibelius played three themes to the painter Oscar Parviainen. These were: Funeral March, A Prayer to God and A Great Feast. The scholar Markku Hartikainen has shown that these themes were probably connected with Jalmari Finne's libretto for the oratorio Marjatta, which Sibelius did not manage to compose despite several attempts. However, the Prayer to God theme ended up as a hymn theme within the finale of the third symphony – and it also appeared on the wall at Ainola, for the theme inspired Oscar Parviainen to produce a painting for Sibelius.

In 1906 Sibelius completed the orchestral poem Pohjola's Daughter. The sketches for the work contain material which ended up in the third symphony. Thus, it seems that the symphony, which in itself was heard as a non-programmatic work, received - as is often the case with Sibelius - its initial stimulus from various programmatic ideas; these lost their programmatic meaning during the process of composition as the material was reworked in purely musical terms.

Sibelius conducted the first public performance on 25th September 1907. The reviews were mixed: Karl Flodin praised the work, but the Helsingin Sanomat reviewer claimed that the direct impact of the work was weaker than that of the first symphony.

Stylistically, Sibelius was now approaching notions of Neoclassical music in ways that his friend Ferruccio Busoni would write about a short time later. Sibelius's third symphony is more condensed than its predecessors. Now there are three movements instead of four, since the scherzo and the finale are combined more organically than in the second symphony.

Romanticism is replaced by functionalism, and the orchestration is lighter than before, with no tuba or harp. In his old age Sibelius was of the opinion that the third symphony need not be performed with an orchestra of more than fifty players.

"The symphony meets all the requirements of a symphonic work of art in the

modern sense, but at the same time it is internally new and revolutionary –

thoroughly Sibelian."

Karl Flodin, critic, 1907

"After hearing my third symphony Rimsky-Korsakov shook his head and said:

'Why don't you do it the usual way; you will see that the audience can

neither follow nor understand this.' And now I am certain that my

symphonies are played more than his."

Jean Sibelius, 1940

"The third symphony was a disappointment for the audience, as everybody was

expecting that it would be like the second. I mentioned this to Gustav

Mahler, and he also observed that 'with each new symphony you always lose

listeners who have been captivated by previous symphonies'."

Jean Sibelius, 1943

The fourth symphony was once considered to be the strangest of Sibelius's symphonies, but today it is regarded as one of the peaks of his output. It has a density of expression, a chamber music-like transparency and a mastery of counterpoint that make it one of the most impressive manifestations of modernity from the period when it was written.

Sibelius had thoughts of a change of style while he was in Berlin in 1909. These ideas were still in his mind when he joined the artist Eero Järnefelt for a trip to Koli, the emblematic "Finnish mountain" in Karelia, close to Joensuu. The landscape of Koli was for Järnefelt an endless source of inspiration, and Sibelius said that he was going to listen to the "sighing of the winds and the roar of the storms". Indeed, the composer regarded his visit to Koli as one of the greatest experiences of his life. "Plans. La Montagne," he wrote in his diary on 27th September 1909.

The following year Sibelius was again travelling in Karelia, in Vyborg and Imatra, now acting as a guide to his friend and sponsor Rosa Newmarch. Newmarch later recollected how Sibelius eagerly strained his ears to hear the pedal points in the roar of Imatra's famous rapids and in other natural sounds.

The trip also had other objectives. On his return Sibelius wanted to develop his skills in counterpoint, since, as he put it, "the harmony is largely dependent on the purely musical patterning, its polyphony." His observations contained many ideas on the need for harmonic continuity. Since the orchestra lacked the pedal of the piano, Sibelius wanted to compensate for this with even more skilful orchestration.

Yet one more natural phenomenon – a storm in the south-eastern archipelago – was needed to get the symphonic work started. In addition, in November 1910 he was preparing the symphony at the same time as he was working on music for Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven, which he had promised to Aino Ackté. The Raven was never finished, but its atmosphere and sketches had an effect on the fourth symphony.

The symphony was performed for the first time on 3rd April 1911, in Helsinki. Its tone was both modern and introspective, and it confused the audience so much that the applause was subdued. "Evasive glances, shakes of the head, embarrassed or secretly ironic smiles. Not many came to the dressing room to deliver their congratulations," Aino Sibelius recollected later. The critics, too, were at a loss. "Everything was so strange," was how Heikki Klemetti described the atmosphere. In the years that followed audiences in many parts of the world reacted the same way.

"The motif of the symphony is a journey to the famous mountain Koli, which

rises 252 metres above the level of Lake Pielisjärvi (…) [As regards the]

magnificent connection which Sibelius has previously made with our people

and its national epic and which has made him so strong and great, this bond

is lacking in the fourth symphony."

Bis, i.e. the critic Karl Fredrik Wasenius in Hufvudstadsbladet, 1911

"The assumptions of the pseudonymous Bis concerning the programme of my new

symphony are incorrect. I guess that they have to do with the topographical

report which I presented to a few friends on 1st April."

Jean Sibelius in Hufvudstadsbladet, 1911

"The future will decide whether in the melodic structure of some the themes

the composer has crossed the boundary that healthy natural musicality

instinctively sets for the play of intervals in a melody."

Heikki Klemetti, critic,1911

"A declaration of war against that superficiality, admiration of outward

devices, empty grandiloquence and overwhelming materialism which is

swallowing up modern music."

Evert Katila, critic in the newspaper Uusi Suomi, 1911

"I feel as if entirely new worlds were now opening for Sibelius as a

composer of symphonies, worlds which have not been shown to others and

which he, with his astonishingly highly developed sense of colour and

melody, can see and describe to others."

Oskar Merikanto, critic in the newspaper Tampereen Sanomat, 1911

"We have very good reasons to call the style of the fourth symphony

expressionism. This is because the line has a dominant position in the

work. (…) The fourth symphony exerts a healthy influence. It involves a

quiet protest against all hollow impressionism, tasteless instrumentation

and low naturalism.

Erik Furuhjelm, scholar, 1916

"I am pleased that I did it, for even today I cannot find a single note in

it that I could remove, nor can I find anything to add. This gives me

strength and satisfaction. The fourth symphony represents a very important

and great part of me. Yes, I'm glad to have written it.

Jean Sibelius in the 1940s

Notes and quotes from Sibelius – The Website: http://www.sibelius.fi

During the First World War Sibelius as a composer led his life "on two levels". His contacts with the outside world were sparse because of the war, and financial pressures forced him to produce a great number of small pieces for Finnish publishers. At the same time he was planning an entirely new kind of symphony. He would write three different versions of it before he was satisfied with the result.

Sibelius had been thinking about the fifth symphony, at least since the spring of 1912 when he was working on other pieces. In the summer of 1914, just after the outbreak of the First World War, he wrote that he had got an idea for "a lovely theme". Then in the autumn of 1914 he wrote a prophecy to his friend Axel Carpelan: "Another depth of misery. But I can already make out the mountain that I shall ascend (…) God is opening his doors for a moment, and his orchestra is playing the fifth symphony."

While Sibelius’s diary notes show that his mood during the fourth symphony was one of determination, the initial stages of the fifth symphony seemed to be filled with ecstasy. "The autumn sun is shining. Nature in its farewell colours. My heart is singing sadly – the shadows grow longer. The Adagio of my fifth symphony? That I, poor fellow that I am, can have moments of such richness!!" he wrote on 10th October 1914. And in November the sentiment grew even stronger: "I have a lovely theme. An adagio for the symphony – earth, worms and misery, fortissimo and sordinos [mutes], lots of sordinos. And the melodies are divine!!"

Sibelius found themes for the sixth symphony while working on the fifth, and some of the material was originally drafted for a lyrical violin concerto. Somewhat later Sibelius was for a time considering a work to be called Kuutar (Luna): thematic material from this also ended up in the sixth symphony.

The symphony was performed for the first time on 19th February 1923. The composer conducted the orchestra himself. The critics praised the "pure idyll" of the symphony, but they would clearly have wished for stronger dramatic contrasts.

Today the sixth symphony is recognised as a masterpiece. Its meaning often becomes accessible only after one has become familiar with the heroism of the second and fifth symphonies, or the profundity of the fourth and seventh symphonies.

Sibelius was going through difficult times in 1923-1924, when he was completing the seventh symphony. He had gone on a tour of Stockholm, Rome and Gothenburg and conducted successfully. However, before the last concert he had taken alcohol. When the concert started Sibelius thought for a moment that he was at a rehearsal and interrupted the performance. The concert went well after this, but Aino, who was sitting in the audience, was terrified. "Everything was chaos in my ears, I was in a state of mortal terror," she said later. From then on, Aino refused to attend concerts in which her husband was conducting.

Sibelius quite often took alcohol to ease his stage fright and the tremor in his hands, which was getting worse with age. Even at home in Ainola it was difficult for him to continue writing the seventh symphony without taking a few glasses to steady his hand. A prohibition law was in force in Finland at the time, and Sibelius was forced to obtain alcohol as a prescription drug.

But the seventh symphony had been slowly maturing in his head for almost ten years, ever since an adagio motif had appeared in his fifth symphony sketchbook. The motif expanded and took on a life of its own, becoming the root of the seventh symphony. In 1918 he wrote: "The seventh symphony. Joy of life and vitality mixed with appassionato. Three movements – the last of them a 'Hellenic rondo'."

But the three-movement plan changed; it was now a work in one movement, and Sibelius was ready to sacrifice his own health for it. The symphony was the result of ten years of contemplation and nothing could prevent the transfer of the masterpiece from the composer's brain onto paper.

Notes from Sibelius – The Website: http://www.sibelius.fi

COLLINS The Sibelius Symphonies, Volume 1

SIBELIUS Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39

1. 1st mvt. - Andante, ma non troppo - Allegro energico (9:19)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andante (ma non troppo lento) (8:50)

3. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo: Allegro (4:36)

4. 4th mvt. - Finale: Andante - Allegro molto - Andante assai - Allegro molto come prima - Andante (ma non troppo) (11:36)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 21-22 February 1952

First issued as Decca LXT 2694

SIBELIUS Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43

5. 1st mvt. - Allegretto (9:26)

6. 2nd mvt. - Tempo andante, ma rubato (12:43)

7. 3rd mvt. - Vivacissimo (5:40)

8. 4th mvt. - Finale: Allegro moderato (13:06)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 11-12 May 1953

First issued as Decca LXT 2815

London Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Anthony Collins

XR Remastered in Ambient Stereo by Andrew Rose

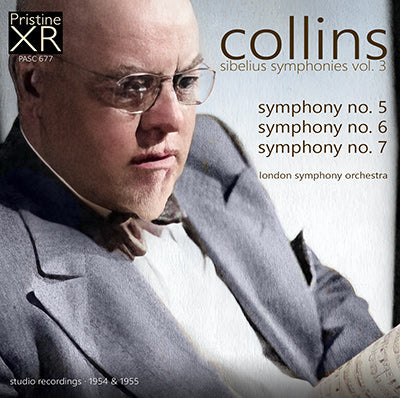

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Anthony Collins

Decca studio recordings

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Total duration: 75:16

COLLINS The Sibelius Symphonies, Volume 2

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro moderato (9:28)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andantino con moto, quasi allegretto (7:30)

3. 3rd mvt. - Moderato - Allegro ma non tanto (7:59)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 5-6 May 1954

First issued as Decca LXT 2960

SIBELIUS Symphony No. 4 in A minor, Op. 63

4. 1st mvt. - Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio (8:50)

5. 2nd mvt. - Allegro molto vivace (4:05)

6. 3rd mvt. - Il tempo largo (8:56)

7. 4th mvt. - Allegro (10:17)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 22-25 February 1954

First issued as Decca LXT 2962

London Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Anthony Collins

XR Remastered in Ambient Stereo by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Anthony Collins

Decca studio recordings

Symphony 3 producer: Peter Andry

Symphony 4 producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Total duration: 75:16

COLLINS The Sibelius Symphonies, Volume 2

SIBELIUS Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 82

1. 1st mvt. - Tempo molto moderato (13:05)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andante mosso, quasi allegretto (8:33)

3. 3rd mvt. - Allegro molto (8:17)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 25-27 January 1955

First issued as Decca LXT 5083

SIBELIUS Symphony No. 6 in D minor, Op. 104

4. 1st mvt. - Allegro molto moderato - Poco tranquillo (8:36)

5. 2nd mvt. - Allegretto moderato - Poco con moto - Poco a poco meno piano - Tempo I (6:48)

6. 3rd mvt. - Poco vivace (3:30)

7. 4th mvt. - Allegro molto - Allegro assai - Doppio più lento (9:48)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 25-27 January 1955

First issued as Decca LXT 5084

8. SIBELIUS Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 105 (19:48)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 22-25 February 1954

First issued as Decca LXT 2960

London Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Anthony Collins

XR Remastered in Ambient Stereo by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Anthony Collins

Decca studio recordings

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Total duration: 78:25